Credits:

Alison Burstein, Curator, Media & Engagement

December 15, 2020

Shaun Irons and Lauren Petty (often known as AutomaticRelease) are interdisciplinary artists who work collaboratively on projects that range from installations and performances to experimental films and interactive video scores. Their collaboration also extends in some cases into their efforts as teaching artists: for instance, Irons and Petty have contributed jointly to The Kitchen’s education programs at Liberty High School Academy for Newcomers for roughly ten years.

In this capacity, Irons and Petty work as part of a team of teaching artists who partner with classroom teachers to integrate theater and video art into the curriculum of English (ELL) classes and after-school programs. Within Liberty’s unique learning community of students who are new immigrants or who still require English acquisition in grades 9 through 12, these initiatives introduce students to art while also using theater and video as tools to promote increased language literacy and self expression. (To learn more about The Kitchen’s partnership with Liberty, visit this Kitchen Magazine piece written by teaching artist Lindsay Hockaday.)

Like all of The Kitchen’s programming, our educational activities are driven and shaped by the artists who lead them. Given the central role that Irons and Petty have played in our partnership with Liberty over the past decade, I wanted to speak with them about their artistic practices and the ways they think about the intersections between their making and teaching. Over Zoom and email, we discussed their recent independent projects, the videos they create with Liberty students, and how they have adapted their methods for both types of work since the onset of the pandemic.

Could you start by speaking about your project All Over Everywhere, which you spent the last few months developing while in residence through 4heads Portal on Governors Island?

Lauren Petty [LP]: All Over Everywhere is an interdisciplinary piece—combining video, live performance, integrated lighting and reactive sound—that engages connections and confrontations between human beings and the imperiled natural world. We originally conceived of the piece as a requiem—a eulogy for our compromised, suffering planet. But since the start of the pandemic the piece has grown to encompass the strange experience of this year—and the multiple anxieties that we are all living through. The title, All Over Everywhere is extremely prescient unfortunately, implying both an ending as well as something that is spreading and uncontained.

Rather than creating a piece that’s trying to educate or engage in a literal way with climate science, our goal is to offer an emotional, atmospheric space for viewers to connect with whatever loss they might be feeling. Hopefully the work can allow a viewer to experience an emotional release—so they then can go back into the world with a new sense of communion and re-energized engagement.

Shaun Irons [SI]: Like Lauren’s saying, we have little interest in directly retelling a story that you could hear on the evening news. Politics certainly plays a big role in our work, but it’s always more about how to transform these literal events and ideas that are happening around us into something more elusive or ephemeral… something with poetic depth. Although our work regularly engages pressing, urgent issues, we find something powerful about making work that is committed to vibrant, imaginative worlds of indefinable beauty.

We’re thinking about how the planet is transforming and changing in catastrophic, horrible ways—how we are continuously losing species, insects, flora and fauna. For All Over Everywhere, we began to think about how to acknowledge that transformation, the horror of that breakdown—how to confront uncertainty with creative action.

LP: We have been developing systems of degrading images and sounds through live processing—disrupting and mutating images we have collected from the natural world with a variety of ineffable textures from shimmering water surfaces and swirling storms to digital glitches. So, in essence, we are using elements from nature to transform—and sometimes attack—other elements of nature.

All Over Everywhere is emblematic of the way that you often shift between or merge aspects of theater, film, and installation in your projects. Could you discuss your practice of working across disciplines?

SI: I think we are always happiest when at any given time we have multiple projects underway: a film, an installation, and some type of live theater piece. And if we have all three of those balls in the air, it is exciting to see how much they inform each other and overlap. But when we’re making a film, I always miss the live aspect—that feeling of it’s eight o’clock, people are in their seats, and ready or not we have to conjure this thing in the room right now.

LP: But now, while working during the pandemic, making a theater piece has become like making a film, since everything is mediated via cameras and technology.

SI: With All Over Everywhere, when we ultimately stage it as a live installation performance, the space will become one big instrument, with elements converging and reacting in conversation with each other: lights and images react to sounds, performers react to cameras, images feedback on themselves. We’re playing the space and we’re not exactly sure where it’s going to go. We invite ghosts into the room—sometimes leading to beautiful, unexpected mistakes and disturbances. That is always something we are going for in our work.

We’ve often joked that we’re like a rock band. We make this really complex album or score during rehearsal, and then we try to play it, and it’s kind of impossible to play it live—it gets beyond us. And so we don’t quite end up with that album—we end up with something else unanticipated. For All Over Everywhere, we’re thinking even more that way. Pushing it into something that we don’t entirely know how to control.

You’ve touched on how All Over Everywhere has evolved on a conceptual level since the start of the pandemic. Building on this, could you talk about how you have adjusted your process of developing the piece in recent months? As you just noted, you frequently move between various working methods and media in your projects: are you finding that these kinds of translations between film and live performance have different outcomes now when they are born out of necessity, rather than out of creative choice?

LP: We have systems of how we typically incorporate media and live performance based on a fluency with technology that allows us to develop ideas and relationships quickly—but the techniques are different for every show. We’ve previously shown All Over Everywhere as an installation while in residence at Yaddo and in Portal on Governors Island (both in 2019). In these settings there was an immersive experience: custom designed plexi-glass panels reflected the projections, literally floating images around the viewer, and there was also surround audio and an interactive, lighting design. So the piece already existed in space and time, and at the onset of the pandemic we were just at the stage where we were ready to incorporate performers into the environment.

SI: Normally in our studio we’d set up the technology and bring performers into the space to begin trying things—developing interactions between the projections, cameras, audio, set elements, costumes, and the live-performers.

LP: But over the past months, we’ve only been able to have rehearsals over Zoom (with performers Elizabeth Carena, Dee Beasnael, and Saori Tsukada). We have a set of references we’re drawing from—ecological writing, poetry addressing nature and science, as well as influences from painting and photography. We have also been working with instructions and movement from exercise videos we have been obsessively doing at home to stay active during the pandemic.

SI: We sent out a range of prompts to performers and said, here’s some text. Read this. Here are some gestures we like. Film yourselves and send it to us. And in our beautiful but crumbling studio on Governors Island, which we were lucky to have had from July through November through a residency with 4heads Portal, we incorporated all these little video clips they sent back.

The performers are not live, but in a sense, we’ve given them so many interesting, strange things to do that there is that element of liveness—they are responding to us from their closets, bathrooms and basements, playing with objects, putting on costumes and exaggerated makeup. We don’t know quite what we’re going to get. When we work, we love to open a room to other people’s ideas and other people’s backgrounds and see what comes out of that, what happens. Performers do things all the time that are unanticipated and that blow your mind.

What role does collaboration play in your practice? As a collaborative duo who works with performers, composers, etc., how do conversations and exchanges with other practitioners feed into or shape your projects?

LP: Shaun and I have collaborated for many years on a wide variety of projects. We have developed a lot of short-hand about ideas, pacing, and intentions and it is rare that we disagree on the direction of a work. Certainly, there are smaller things we disagree on in the moment—but rarely the larger picture in terms of what we are ultimately after.

SI: Lauren and I are crazy enough to do pretty much everything when we are making our work—shooting, editing, directing the piece, and designing the system to run it. However, we do have certain things that we each separately gravitate toward. I’m usually dealing with cameras, framing, the overall visual look of the piece and set, and Lauren focuses more on technology and programming. But we do overlap. There is often a point where the piece becomes too big, too complicated for us to manage alone—particularly live-performance and installation works get very complex over time—and then it’s great to have other people in the room.

We build a world for the performers to exist in and ask them to engage with the technology: they trigger sound/image from stage, move and re-frame cameras during a show, activate lights, and re-arrange set pieces. We never want to hide the human element driving things—we are always OK with seeing a camera being refocused, revealing the in-between stages, the parts that often get cut out. This way of working was very evident in both of our performance works—Keep Your Electric Eye On Me (2015), a multimedia live performance exploring dual-realities and hysteria, and Why Why Always (2017), a live cine-performance riff on Godard’s film Alphaville—where it was an all hands on deck approach.

LP: We have done video design for other artists—theater, dance, opera—and every time we agree to work on a show, there is something, some image or idea, that we initially think, “we have no idea how to make that happen!” But, somehow we always figure it out—and it is always exciting to try something outside of our current methods and skill sets. It’s a real learning process, and whatever we discover through this process usually has a way of working its way back into our own work.

In terms of collaborators for our projects, we often seek people who are willing to contribute to the work more than design an entire portion of the show. Meaning that we prefer collaborators who provide materials and building blocks, but then allow us to design from there. For instance, we are currently working with an amazing composer named Chris Cerrone, who has contributed a variety of audio drones (processed with recordings of water and insects) that we are sequencing and layering—and he will also be writing a few stand-alone melodic phrases that we will place throughout the work.

SI: We welcome other people’s ideas—especially when rehearsing with performers—and happily bring their influence and particular qualities into the work. But at the end of the day, we are the ones responsible for shaping the piece.

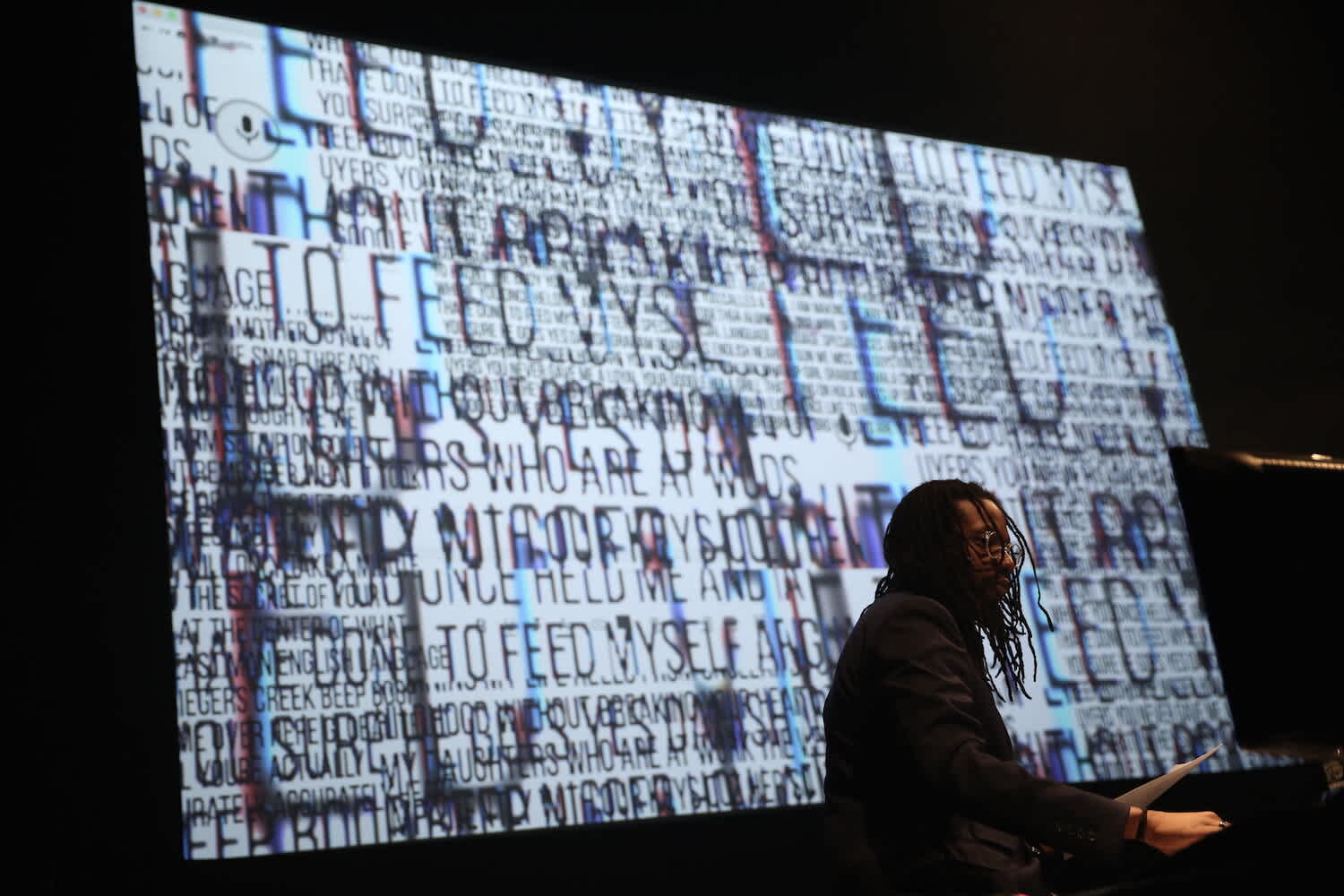

One of the primary programs you contribute to at Liberty High School is the twelve-week teaching residency that pairs Kitchen artists with an English (ELL) class each semester: for each iteration of that residency, you collaborate with other teaching artists to guide students through the process of creating and staging a multimedia production that is based on or inspired by a work of literature. In the final weeks of the residency, you direct and film students performing various scenes from the play against a green scene, and then you edit this footage to depict different settings. The students stage the final production at The Kitchen in our black-box theater, and the videos are a central component of the show—they are projected behind the stage to complement the live acting. Has your work on those programs informed your own projects over the years? Are there any direct or indirect exchanges between the videos that you work on with the students and the pieces that you create independently?

SI: When we are working with the kids, I always love to see what they’re going to do. It’s great because it gets us out of our own way of working and out of our own heads and frees things up and inspires us. This past Spring, when we finished the semester working remotely due to COVID-19, the students sent us videos that they filmed in their own homes in response to prompts from us and the other teaching artists. So we got a glimpse into their own lives. Maybe they had a couple of minutes to get this shot. Maybe their mom or sibling was in the other room calling them, and they were doing a dance, and they just totally went for it without any shyness. They were just giving themselves.

LP: Yes, those videos were beautiful in their realness. There is a certain freedom in working with footage made by and with the students. There’s an expectation in our own work that if a performer sends us something that we intend to use, there’s a certain level that it has to reach, or it has to connect aesthetically with what we’re trying to do. So, with the Liberty students there’s a kind of freedom since the purpose is different. And also that inspires us to play around with the craziest effects and goofiest smash cuts and backgrounds and titles—things that we would not typically use in our own work.

SI: We bring years of our experience into the collaborations at Liberty, which are mad, chaotic setups for shooting videos with students very quickly in what are often too hot, brightly lit classrooms with no space. But we have to make the shoot happen now because the kids are there, practicing their lines, the costumes are piled up, and the final performance is happening in a few days. If it was our own work, sometimes we might think, “we’re just not prepared today; let’s do it next week.” And this immediacy has influenced us so much—that sense of, no, it’s happening right now. We are going to shoot this and we are going to get something valuable out of this. There’s no time to be precious with it.

Sometimes when we work with students they are afraid to perform, and then it’s a matter of trying to guide them out of themselves to open up, be present, and be weird. It’s tough. It’s embarrassing. You’re in front of your classmates. But it’s cool to crack yourself open and give something of yourself. And that’s something that we keep in mind in our own work all the time, to not hold back, to not think, oh this feels corny here. That’s probably the good stuff.

LP: And another thing is that over the years we’ve seen so many people that we’ve worked with really grow. At first when we meet them, they’re often freshmen and English is relatively new for them. And then in a few years, they end up being the star of the show. It’s been so inspiring for us to see that transformation, that growing of confidence in them.

SI: We also just love the idea that this is a program that engages students from all over the world—and they converge to tell a story—collaborating with each other, us and the other teachers. Seeing this diverse group of students coming together to create a multimedia theater piece is always incredibly inspiring.

Shaun Irons and Lauren Petty (AutomaticRelease) are Brooklyn based multi-platform artists who make interdisciplinary performances, multi-channel installations, experimental films, documentaries, and interactive video scores to accompany live performance. Their hybrid work has been exhibited in diverse locations in New York and internationally including BAM’s Next Wave Festival, The Brooklyn Museum, Abrons Arts Center, The Chocolate Factory, Anthology Film Archives, REDCAT (Los Angeles), Z Space (San Francisco), CURRENTS New Media Festival (Santa Fe), Rencontres International (Paris/Berlin) and the Museo Nacional (Havana, Cuba). They have received numerous awards including two NYFA Fellowships and grants from the NEA, NYSCA, NYC Made in NY Women’s Fund (NYFA), Jerome Foundation, Greenwall Foundation, the Asian Cultural Council, Experimental Television Center, Bel Geddes Design Fund, and the Mertz Gilmore Foundation. They have also had multiple creative residencies from MacDowell, Yaddo, LMCC, Harvestworks, 4Heads Portal, Signal Culture, Bogliasco Foundation, the Camargo Foundation, and the Tokyo Wonder Site. Currently, they are completing their interdisciplinary installation/performance, All Over Everywhere, which will be presented virtually in early spring 2021 (and as a live performance hopefully soon after!). To learn more, visit the artists’ websites www.automaticrelease.org, www.shaunirons.com, and www.laurenpetty.org.

FUNDING SUPPORT

The Kitchen’s arts education programs at Liberty High School Academy for Newcomers are made possible with generous support from IAC and Lotos Foundation, and in part by public funds from New York City Department of Cultural Affairs in partnership with the City Council.