Credits:

Kathy Cho, 2020–2021 Curatorial Fellow

December 14, 2020

Density 2036 is a twenty-four-year project begun by Claire Chase in 2013 to commission an entirely new body of repertory for solo flute each year until the 100th Anniversary of Edgard Varèse’s groundbreaking 1936 flute solo, Density 21.5. For Density 2036: part vii, Chase invited Liza Lim to compose new work. Lim is an Australian composer, educator, and researcher whose music focuses on collaborative and transcultural practices. For the commission, Lim composed Sex Magic for contrabass flute, electronics, and an installation of kinetic percussion instruments. Sex Magic will be performed by Claire Chase as part of Density 2036: part vii and more at The Kitchen at Queenslab, premiering via livestream on December 18, 7–9pm EST.

In advance of the performance, Curatorial Fellow Kathy Cho spoke with Lim about her process for composing music, preliminary research for Sex Magic, and what it was like working with her collaborators for Density 2036: part vii.

What is your usual process for starting to compose a piece of music?

A consistent starting point for a lot of my work is to grow a collaborative relationship with a musician and their instrument. I draw a lot of inspiration from the context surrounding a player and their instrument—I want to know about their stories and who they are. I research the histories and performance practices of their instrument—all this starts to create a symbiotic web of ideas and a kind of energetic signature that I respond to in music.

When Claire reached out to you about a potential commission, what initially interested you about the Density 2036 project?

Well, it was quite daunting to think about writing a piece for solo flute when so many pieces have already been written. But of course, Claire’s vision has enabled composers to go beyond the standard idea of a flute solo as an acoustic piece (which by the way is still great!) to works with electronics, expanding all the way to projects such as Pan (2017–18), the music-theatre work for flute, electronics, and community performers by Marcos Balter. Claire initially asked me to write a piece in early 2018, and I didn’t find a way into the idea until towards the end of the year when we discussed my composing for Bertha, her contrabass flute. That her flute has a name and a personhood brought everything to life for me.

You have previously described your practice as being transcultural and being about intercultural exchange. Could you talk more about the research and influences behind Sex Magic, from the historical and mythical references, to the mix of various instruments such as the Aztec death whistle and electronics? How did they all come together?

The music was very much prompted by Claire’s connection to Bertha which then suggested kinships to particular blown instruments. A key starting point was to look at various “big flute” traditions. In Northern Australia, there is the yidaki or didjeridu which is a buzzed, end-blown hollow wooden tube—it’s a “flute” but is more akin to a drum in that it’s used to produce rhythmic patterns within a drone. Geographically nearby in Papua New Guinea, there are also incredible sacred big flute traditions. The flutes are made of bamboo and often played in pairs to produce hocketing or interlocking rhythms out of single notes and their overtones.

I was intrigued to find out more about the gendered contexts of these big flutes, which are taboo for women to play (certainly the case for the yidaki) and, in some places in New Guinea, taboo for women to see, touch, or hear. The origin stories for these instruments often focuses on women’s power that had been wrested away from them by men. I don’t focus on those specific cultural reference points, but my work, as alluded to by the title, is making a claim on women’s cultural space and female power.

Flutes and drums in many cultural traditions are not just “instruments” but are regarded as sentient beings, as power objects that contain wisdom energies. There are a number of other flute-instruments in my piece including the intimate-voiced ocarina, found in both Chinese and Mesoamerican traditions. At the opposite end of the expressive scale, there is also the Aztec “death whistle” which is a double-chambered, often skull-shaped clay whistle that produces a howling or screaming sound. Archaeological studies associate the instrument with Aztec sacrificial, death, and war rituals, and in my piece it is played as the embodiment of the primal power of rage.

Regarding Sex Magic, I read that you were able to have a creative development session with Claire Chase and electronicist Levy Lorenzo. What initial ideas did you have for the commission and how did it evolve after meeting with Claire and Levy?

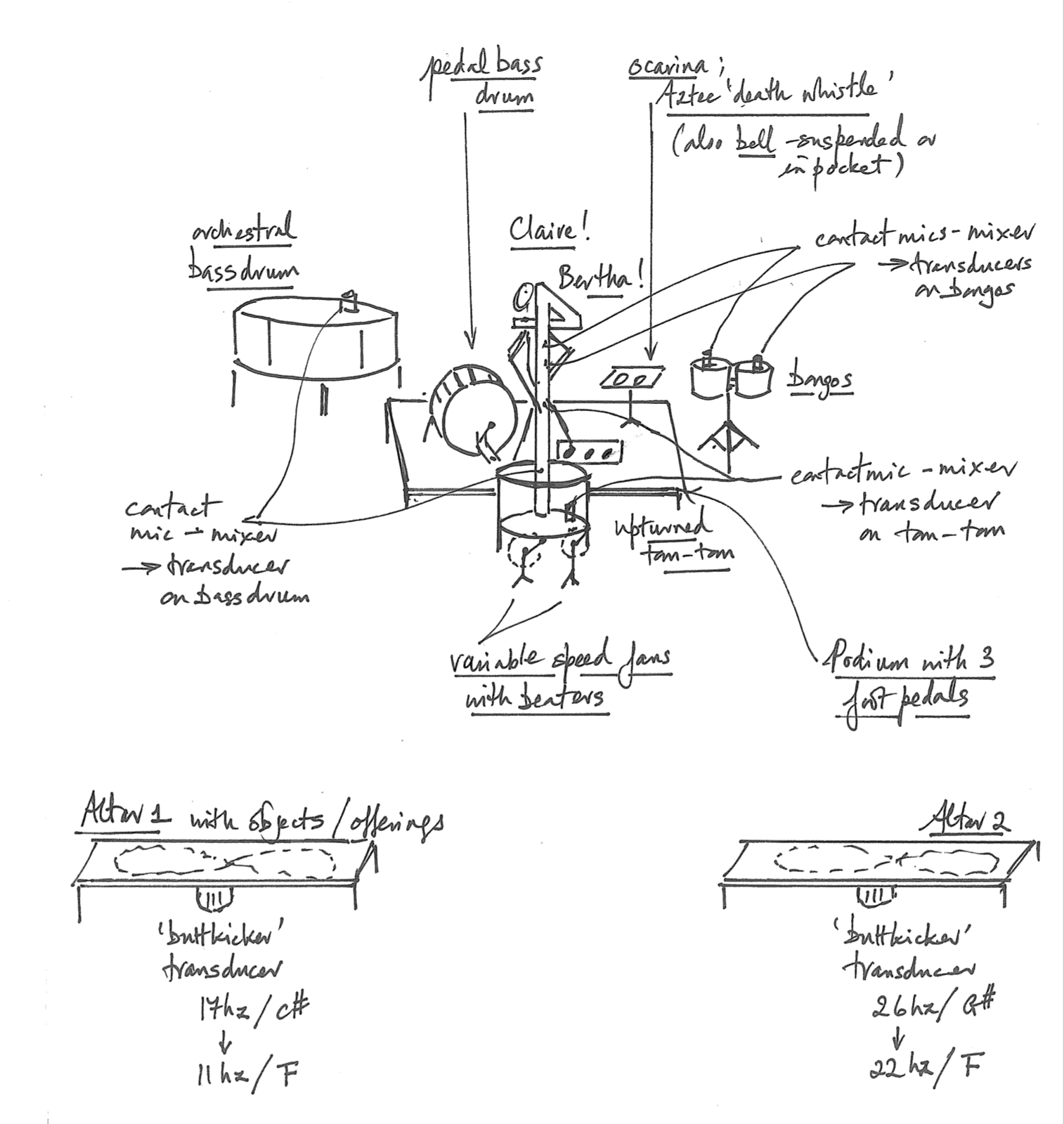

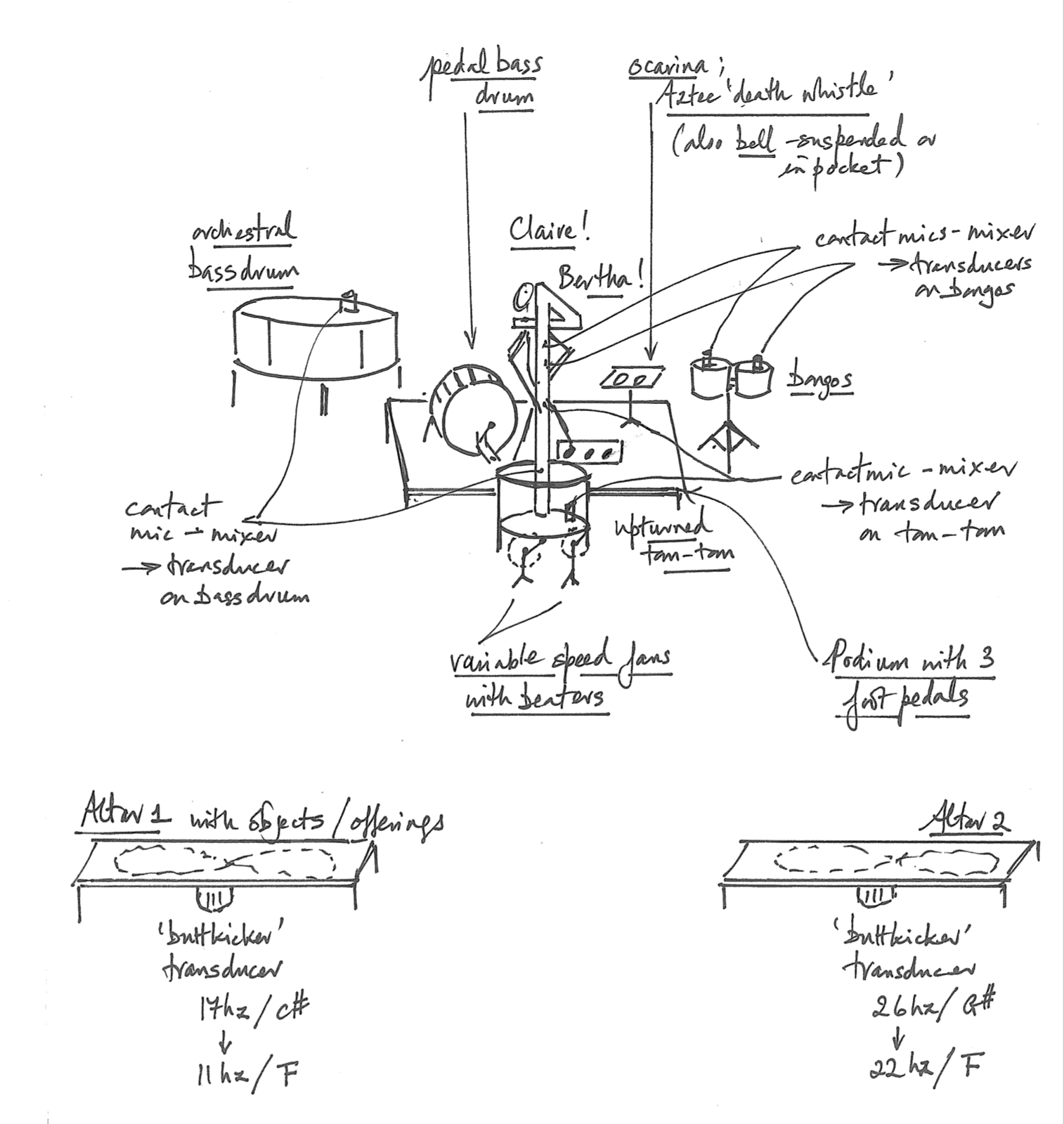

In that workshop in September 2019 in New York we were exploring the idea of “flute as drum.” That turned out to be an incredibly productive notion leading to various kinds of set-ups with contact mics and transducers on drum surfaces creating fabulously rich overtone/feedback sounds. We also experimented with the flute amplifying and modulating percussive sounds created by rotary fans striking drum skins as well as other drumming elements. Levy was crucial to the development and build of the kinetic instruments. It has resulted in a work in which the reach of the body of the player playing an instrument is extended out in space in an installation of resonating drum skins and other surfaces.

How did your process of incorporating archives and collective memory into your contemporary practice translate to the creation of Sex Magic?

The forty-five-minute piece is divided into a number of different parts, each referencing some aspect of what I describe as “an alternative cultural logic of women’s power as connected, in part, to cycles of the womb—the life-making powers of childbirth, the ‘skin-changing’, world-synchronising temporalities of the body, and the womb centre as a site of divinatory wisdom and utterance.”

One thing that keeps coming through in the piece is that all matter and energy is alive and conscious and in a process of transformation—you hear that in the way the deepest sub-tones generated on the flute vibrate the objects on the two altars placed in front of it, and you see the organising principle of vibration. It speaks to the inescapable communion between everything.

I heard you were able to visit Queenslab, the location where the performance will take place, around fall 2019. How did the space inform the creation of Sex Magic?

Queenslab is a fantastic space. I love these kinds of industrial/warehouse spaces which are full of memory traces. One feels the dialogue between past-present-future in these kinds of history-filled spaces—they invite ritual in that one can ride a slipstream of time within them. So yes, the space also coloured my ideas for the piece.

Since the pandemic has restricted travel, and you are based in Australia at the moment, to what extent have you been in touch with Claire about rehearsals, the performance aspect of Sex Magic? How collaborative has the process been?

I’ve been getting tantalising excerpts on Whatsapp and Dropbox. What I’m excited to hear are all the emergent aspects of performance that are not in the score but are generated in the act of playing—the rhythm of Claire’s breath that is like a tai-chi dance with Bertha’s sonorities. All the transient sounds that create a “third space” of fluctuating overtones and colours that trace the movement of the circulating airflows across the planes and within cavities of the flute.

As a lot of our conversations have moved online due to the pandemic, how, if at all, have these ways of communicating changed and affected your practice?

We’re lucky to have audio-visual technologies that connect us relatively seamlessly across vast distances and time-zones. In COVID times, out of necessity, we’ve had to adapt to these things for working, teaching, etc. But I think we’ve also found powerful and creative ways to connect that we wouldn’t have necessarily turned to in times where co-presence was more possible.

I was on a Zoom session a few days ago to perform Pauline Oliveros’s The Witness (1989) organised by Claire. It was 5:30am for her in upstate New York and then there was anthropologist Eduardo Kohn in Canada; Sápara spiritual leader Manari Ushigua with Belen Paez who is an environmental activist (one of the founders of the Sacred Headwaters Initiative) together in the Ecuadorian Amazon; whilst it was my evening in Melbourne, Australia. It was quite extraordinary to be sharing musical/spiritual space and discussing Pauline’s ideas in the context of thinking about ecological ethics and cosmologies—over an internet connection.