Credits:

By: Alexandra M. Thomas

September 9, 2025

This essay examines the aesthetic and political contours of fat and Black embodiment in the mixed media artwork of Sondra Perry. Utilizing video, 3D avatars, performance, and sculptural installations, Perry crafts spaces where racialized, gendered, and non-normative bodies can be reimagined outside the logics of surveillance, commodification, and control. Her practice centers on how bodies are not only represented in visual media but also shaped, constrained, and disciplined by sociopolitical systems. In particular, I am drawing attention to how notions of fatness and Blackness manifest in Perry’s Graft and Ash for a Three Monitor Workstation (2016). The work was on view in her first solo institutional exhibition, Resident Evil, at The Kitchen in late 2016.

Displayed against the backdrop of a gallery painted in chroma-key blue, the work is a triptych of LCD monitors mounted atop a red stationary exercise bike. The three large monitors, arranged side-by-side in a horizontal formation, create a panoramic viewing experience of synchronized yet distinct content. On the screens, Perry’s avatar appears as a floating head against varying chroma-key and cloudy orange waves. The avatar is brown-skinned, bald, slender, and speaks in a robotic voice. Perry has designed the avatar to narrate her digital becoming and the limits of wellness under racial capitalism while relaxing, ambient soundtracks play in the background. Found footage from a Nigerian Christian television network is interspersed along with quotes from research articles about race, capitalism, and productivity. A moment in which Perry’s avatar recounts, “My fatness could not be replicated,” is especially thought-provoking. The avatar shares that she was coded in Perry’s Houston studio in April 2016, but the software used was unable to accurately represent Perry’s embodiment, due to the fact that her body did not exist as an available template. The failure of the software to represent fatness is one such way that non-normative bodies are effectively in/visibilized.

Although the skin tone of Perry’s avatar is relatively accurate, the software offered templates for racial phenotypes with stereotypical features of European, African, and Asian people. While fatness is invisibilized, race is envisioned in discrete racial categories despite the ability to manually edit certain features like the avatar’s skin color and facial features. The racial types offered as templates coincide with historic imperialist categorizations of the so-called “races” of the world based on visual markers of non-European ancestry. That fatness fails to appear as an option for Perry’s digital avatar reinforces the entwined nature of Blackness and fat embodiment. I interpret the invisibility of fatness along with the visibility of racialization as one such way that Perry is exploring how technologies render the body visible and invisible in inherently political ways. A fat Black feminist reckoning that engages with the entangled histories of anti-Black surveillance and fatphobic initiatives illustrates how such processes reproduce ideals of beauty, fitness, and productivity with capitalist interests.

Perry’s immersive approach makes it possible for viewers to ride the stationary bike while watching the screens, listening to the relaxing soundscape, and pondering these interlocked dynamics of subjectivity and embodiment under racial capitalism. The stationary exercise bike represents the phenomenon of office workers utilizing hybrid desk-bikes to remain physically active while staying seated at their desks and being productive for the company. Meanwhile, the irrepresentability of Perry’s fat embodiment in digital form indicates how human biases, such as fatphobia, are encoded into digital software. Coders are not objective, and the technological world is ultimately manmade and replete with biases toward Eurocentric and thin standards. Especially since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, the popularization of walking pads and standing desks parallels such workday habits that purportedly promote wellness in the workplace. The often unspoken aspect of such workplace norms is that the corporate desire for employee wellness only extends insofar as productivity is ensured. Moreover, there is a fatphobic agenda implicitly attached: workplace initiatives for walking or cycling at one’s desk are couched in rhetoric aimed at burning calories while working a sedentary job.

Ironically, a majority of the workstation bikes and treadmills have strict weight limits that make these devices inaccessible to much of the target population—fat people, or people who someday could be fat. Like the software that could not produce an accurate representation of Perry’s body, the devices designed with fat people in mind exclude many of these individuals from using them. As opposed to the neoliberal imperative to “include,” what if we interpret such anti-fat biases as grounds for an anti-capitalist fat politic? In failing to appear in the digital software, or even on the workplace exercise machines, fat Black women have the radical opportunity to rewrite anticapitalist and antisurveillance politics from their position.

Fat Black feminist scholars have theorized the relationship of fatness and Blackness to labor, exploitation, and fugitivity (1). Ultimately, the notion of being too corpulent and therefore unproductive has been scripted onto Black bodies since slavery and colonialism. Fatness has therefore been demonized as a gluttonous space of unchecked desire, entwined with Blackness. Moreover, the hypervisibility of fat and Black women as dutiful laborers (the “mammy” archetype) and unemployed drains on the economy (the “welfare queen”) shows how such ideology is concretized in the American imagination. There is a moral panic surrounding the so-called “obesity epidemic” and the popularization of new weight-loss drugs and calorie-counting apps aimed at biohacking fatness out of existence. At the same time, American workplaces are focused on promoting mind and body wellness to ensure capitalist productivity. Perry’s avatar is riffing on the dynamics of workplaces exploiting their Black workers while glamorizing a trendy sense of wellness that is nonetheless tethered to working more instead of less. Perry’s work mobilizes necessary criticism of capitalist technologies designed to surveil and control bodies to fit thin, Eurocentric standards.

One of the found footage scenes that appears in the workstation videos is a 2013 scene from Emmanuel TV, a Nigerian Christian television network, featuring a woman named Mrs. Obi Ofoegbu. According to the Emmanuel TV website, Ofoegbu struggles with “obesity” and a desire to stay in bed all day. In the scene, she is finally “delivered” from the demon, supposedly making her fat. Such footage, despite its rootedness in real and harmful intra-community fatphobia stemming in part from white supremacist standards, presents an ironic engagement with fatness that underscores Perry’s work’s relationship to fat embodiment. The artist’s appropriation of the scene is dark humor that accentuates the campiness of the Black church while simultaneously gesturing to how religiosity coincides with fatphobic rhetoric. 18th and 19th century teachings of the Protestant work ethic and self-discipline contribute to the lasting positioning of thinness as the pinnacle of moral and racial superiority.

From today’s vantage, nearly a decade after it was made, Perry’s 2016 workstation resonates immensely. The ongoing COVID-19 pandemic has transformed the workplace with the proliferation of remote work and its own unique demands. In contrast, “essential” and service workers who did not have the opportunity to work remotely during the heights of the pandemic continue to work in person. Masking in the wake of COVID-19 has allowed for anonymity and freedom from surveillance during political protests against racism, imperialism, and genocide, while affirming commitments to keeping one another safe. Due to medical neglect and a lack of adequate resources, fat Black women face disproportionately higher rates of severe illness and death from COVID-19. What does it mean then to think through fatness and Blackness in Perry’s work at this particular time in history?

Surveillance is at the root of these overlapping themes of embodiment, race, technology, and capitalism. Covering one’s face with a mask to limit COVID transmission remains a timeless tactic against surveillance technologies employed by the state. 2025 also marks a decade since Simone Browne’s Dark Matters: On the Surveillance of Blackness (2015) — the text on how surveillance of Black communities remains a core policing tactic in the West since slavery, even when the technologies themselves transform with time. Facial recognition systems, for example, are among the many biometric technologies weaponized against Black and brown communities. Activists and everyday marginalized people are increasingly victimized by surveillance technologies such as drones, GPS tracking, and social media monitoring utilized by law enforcement and the state at home and abroad. For fatness to evade representation in the digital software Perry used raises the possibility that fat embodiment might resist capture by surveillance technologies. To be unrecognizable in the face of technologies aimed at surveilling and controlling could be a revolutionary gift. In contrast to the invisibility of fatness in the digital software, Perry experiments with how Blackness does appear in these technologies, while pushing the boundaries of its visibility. Her avatar is brown-skinned but certainly not a mirror image of the artist herself or any other Black woman. The glitchy and animated aesthetic of the avatar operates as abstraction in its inability to fully capture a photo-realistic representation of Perry.

Resident Evil at The Kitchen generally wrestled with questions of racialized representation within digital media. In the years since her exhibition at The Kitchen, Perry has remained committed to experimenting with new media techniques and mixed media installations, while advocating for net neutrality, open-source software, and critical engagement with the relationship of digital media to race and gender. An open and equal internet would allow Black communities to freely share information and protect their online privacy without companies or the government tracking their online activity. The infrastructure of the web is often imagined as an already neutral territory, but algorithmic biases are ingrained into all digital technologies. There are racial and embodied disparities in content that gets flagged as obscene on social media, search engines that are designed to reinforce whiteness in what comes up first as answers, and facial recognition systems that consistently misidentify people of color. The internet amplifies the existing hierarchies of the world around it, but artists like Perry experiment with using technology to imagine an otherwise experience of the web.

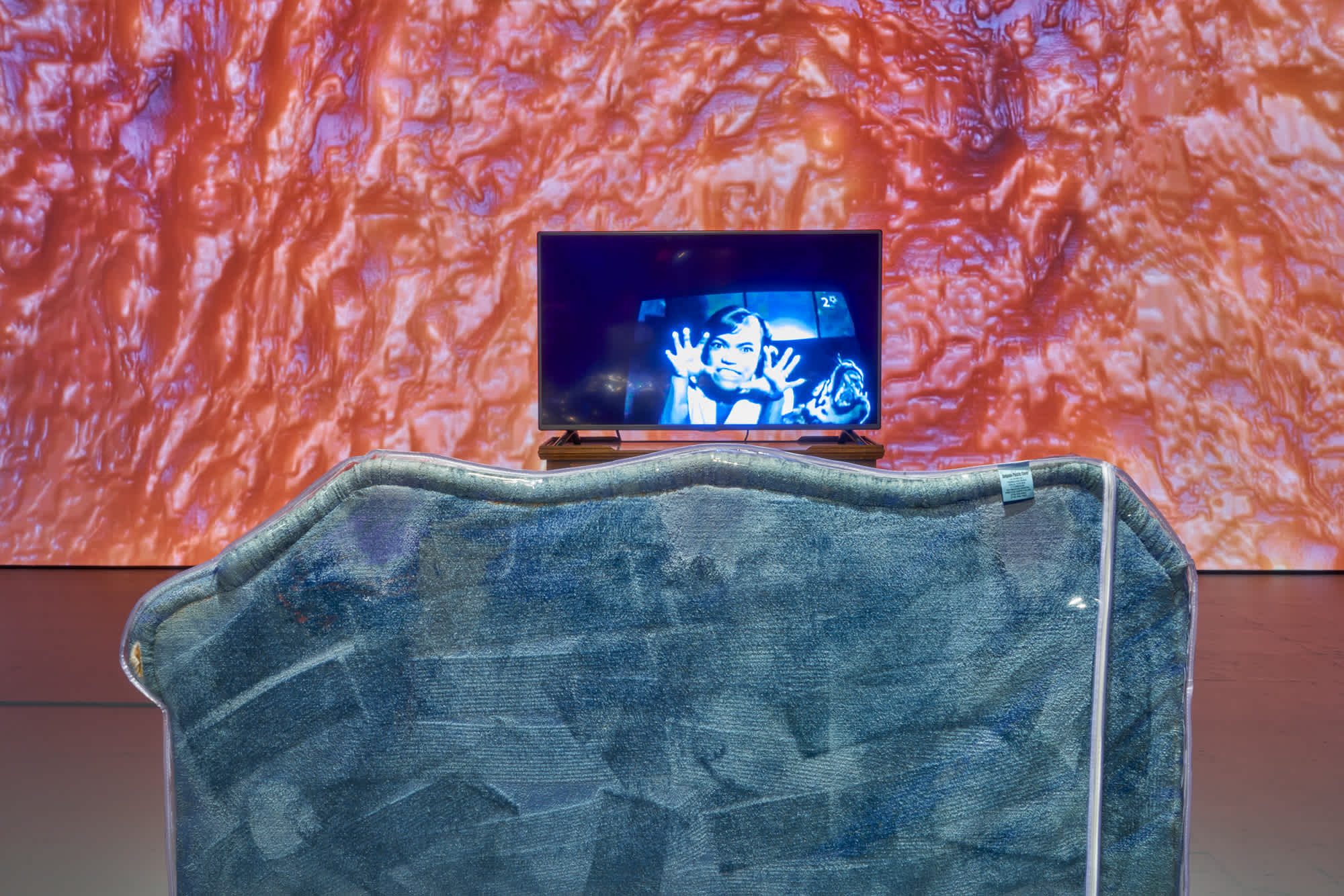

Perry’s work continues to pose abstraction and experimentation with digital technologies as a strategy against the racism and surveillance embedded in the internet. Her recent exhibition at Bridget Donahue gallery in 2023 was titled with a horizontal black bar instead of words, evoking a “redaction” of sorts that reads as another form of antisurveillance and experimenting with the limits of abstraction. The exhibition included sculptural elements in the form of barbershop chairs, along with a video featuring AI-generated footage of Black people in a barbershop that Perry glitched and transformed into a surrealist vision. As in her earlier work, Perry grapples in these newer pieces with experimental representations as an alternative to realist displays of Black life that are prone to voyeurism and surveillance. While these recent works do not explicitly grapple with fatness, I am reminded of the words of Perry’s 2016 avatar when I look at them, who tells us her “fatness could not be replicated,” the pain of productivity and exhaustion, and inquires about how we feel in our bodies. The Black hair salon is a space of labor and care that exceeds the frame of American surveillance capitalism and productivity norms. Perry invites AI software to represent this space, then subverts its representation by glitching and looping it.

Ultimately, a fat Black feminist reckoning with Perry’s Graft and Ash for a Three Monitor Workstation (2016) and its role within her general practice highlights how digital imaging technologies are intimately tied to racist and fatphobic forms of governance, despite the possibility of resisting these measures through appropriating those various technologies. Fatness, within this frame, becomes a site of rupture: fatness is noncompliant, excessive, and unruly in neoliberal capitalist health discourses and thus subjected to regulation and stigmatization. Yet, her turn to thinking with the space of the beauty salon in many ways illustrates how Black communities are self-fashioning and laboring in alternative ways that stand in contrast to these forms of governance. Perry embraces opacity in a refusal of readability, opening a critical space for bodies that defy the pressure to conform.

(1)See Ebony R. Oldham’s “Black Fat, Fit Slave” (2025), Da’Shaun Harrison’s Belly of the Beast (2021), Sabrina Strings’ Fearing the Black Body: The Racial Origins of Fat Phobia (2019), Courtney Patterson-Faye’s “What if Black Studies studied fat for real for real?” (2024), and Andrea Shaw Nevins’ The Embodiment of Disobedience: Fat Black Women’s Unruly Political Bodies (2006).