Credits:

Elana Engelman-Lado, Fall 2019 Curatorial Intern

May 4, 2020

IN NOVEMBER 2019, Audika Records released Iowa Dream, a compilation of demos Arthur Russell recorded for major labels. This album is the most recent addition to a collection of at least nine posthumous releases of Russell’s work, indicating a seemingly ever-growing interest in the artist and his music. Best known as a cellist, singer-songwriter, composer, and electronic musician, Russell wove together dance, pop, classical, and folk music. His skill for inter-genre synthesis had a lasting impact on his peers and continues to influence contemporary artists. Though his career was cut short by his early death from AIDS-related illness, his posthumous releases continue to expand our understanding of his work.

While Russell’s music has received increasing attention, his curatorial work has rarely been the subject of study. In light of the recent Iowa Dream release, I was inspired to look at Russell’s relationship with The Kitchen and his work as Music Director from 1974 to 1975. From his early encounters with The Kitchen through his time as Music Director and later in his performances at the space, Russell injected into the institution a boundary pushing, genre-blending ethos, setting a precedent for artists who built on Russell’s legacy long after his tenure.

RUSSELL ENTERED the New York music community in 1973 when he enrolled in the Manhattan School of Music, uptown. But by the end of his first year at school, Russell’s attention had already migrated south to Lower Manhattan, prompting him to join the downtown scene of the 1970s anchored around spaces like The Kitchen.

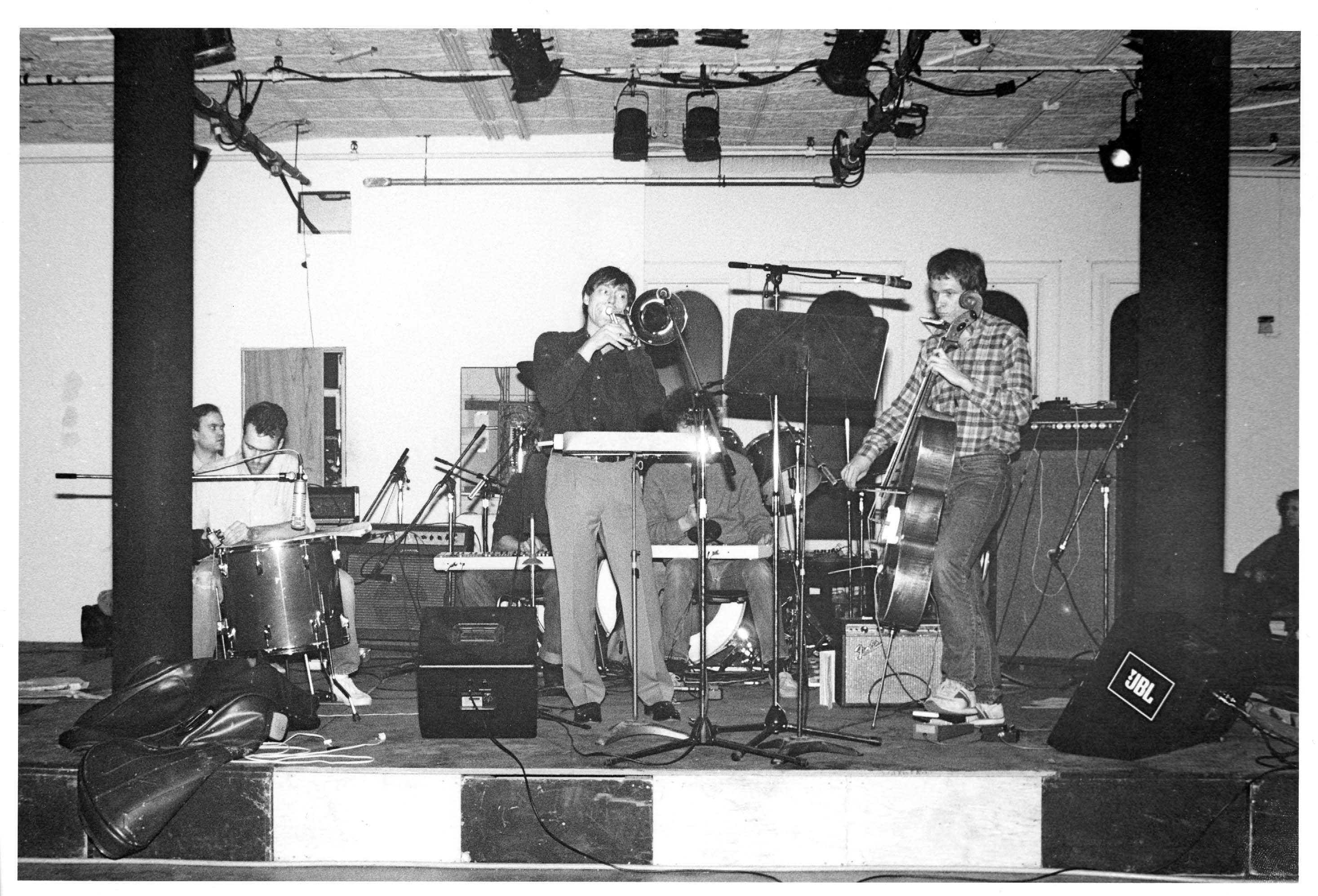

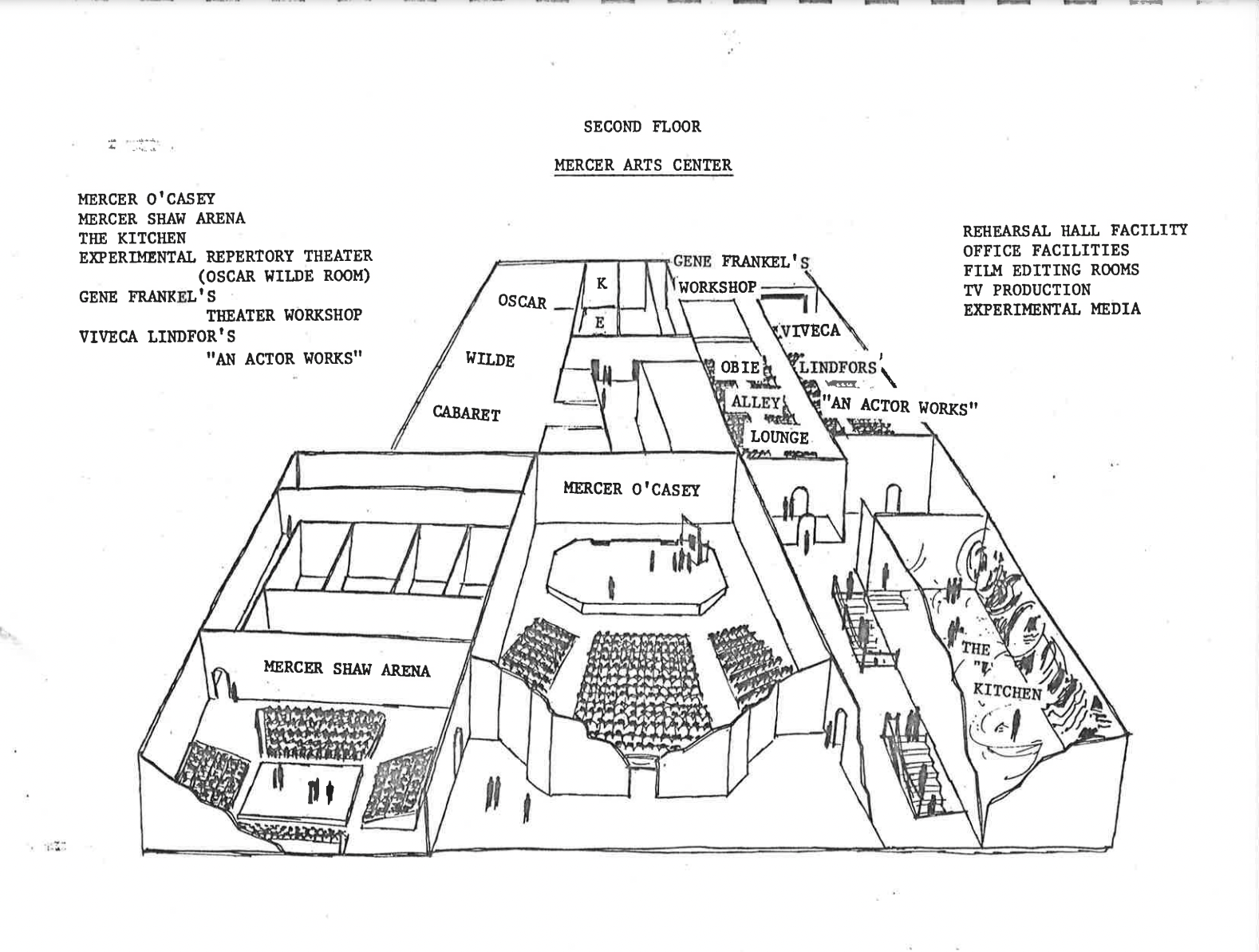

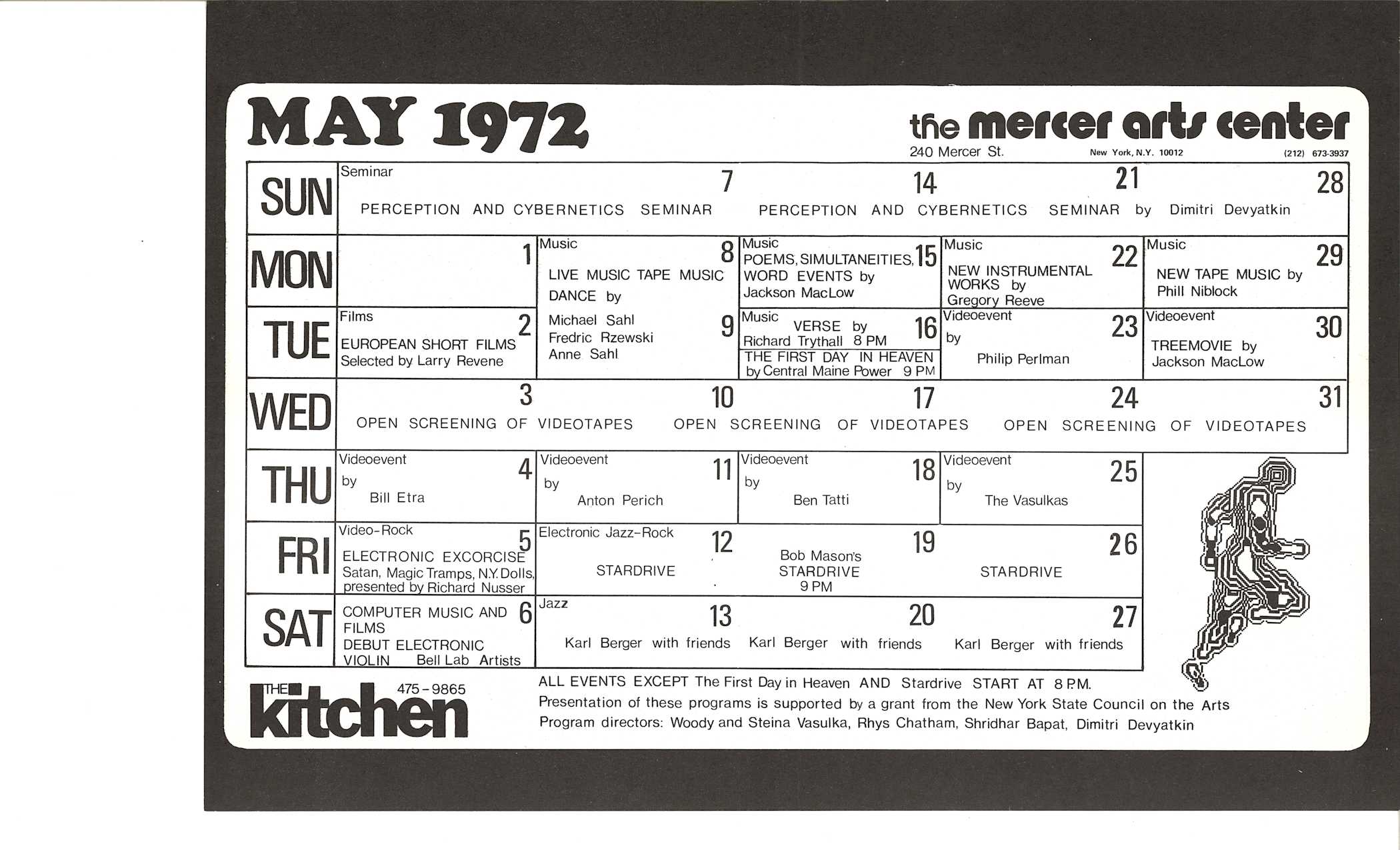

When Russell encountered The Kitchen in 1974, it was a young organization that already had a strong track record of music programming. Rhys Chatham, a nineteen-year-old musician and composer, had initiated the music program in 1971—the year The Kitchen was founded—by starting a series of events on Monday nights. Taking place in The Kitchen, which was originally located within the Mercer Arts Center in Soho, these music events happened alongside the programs that neighboring performance and exhibition spaces hosted within the Center.

For instance, on the opposite side of the floor from The Kitchen, the Oscar Wilde Room hosted regular performances by artists including Eric Emerson and his glam punk group the Magic Tramps, proto-punk groups like the New York Dolls and Wayne County & the Electric Chairs, and a rotating roster of touring performers. There was overlap in programming that took place across the different spaces within Mercer Arts Center: The Dolls, for example, performed at The Kitchen on May 5, 1972 and, later that year, had a months-long residency at the Oscar Wilde Room.

Primarily, though, under Chatham’s direction, The Kitchen’s music program focused on the conceptual experimentation of artists from New York’s downtown scene, creating space for composers and performers who had limited opportunities to present this work in other local venues. Jim Burton assumed the role of Music Director in 1972, and continued programming in this vein.

In the fall of 1973, The Kitchen moved out of the Mercer Art Center and relocated to a loft space at 59 Wooster Street in Soho. Tim Lawrence—author of Russell’s biography Hold On to Your Dreams: Arthur Russell and the Downtown Music Scene, 1973–1992—describes a change in atmosphere after the move, writing that the new space gave The Kitchen a different sense of prestige. Lawrence notes that the Director at the time, Robert Stearns, had the impression that while some musicians might have enjoyed the exposure and interplay that was present in the shared setting of the Mercer Arts Center, other composers were pleased to be removed from the more raucous backdrop. The potential for tensions between the downtown artists curated by The Kitchen and the wide-ranging artists brought in by other spaces in the building dissipated with the move, postponing a debate within The Kitchen about the differences in the artistic merit of avant-garde experimentation, pop aesthetics, and entertainment.

AT CHATHAM’S SUGGESTION, Russell assumed the role of Music Director less than a year after The Kitchen moved into its new space. The two had met earlier in the year when Russell played cello alongside Kitchen regular Jackson Mac Low for a radio broadcast. These collaborators were attracted to the mixture of classical, folk, and popular music techniques they heard in Russell’s playing. His curatorial direction built on this style.

Stearns recalls Russell “pushing the edges of pop music” as Music Director, but this direction wasn’t immediately apparent. The first months of his programming were representative of the downtown avant-garde scene that had found a home at The Kitchen from the start—with performances by many of the leading figures in the minimalist, electronic, and experimental movements from New York’s downtown scene, including composers and performers such as Éliane Radigue, Laurie Spiegel, and La Monte Young. This was consistent with Russell’s own interest in minimalism, evinced in the elemental structures and musical reductions he played with in his work.

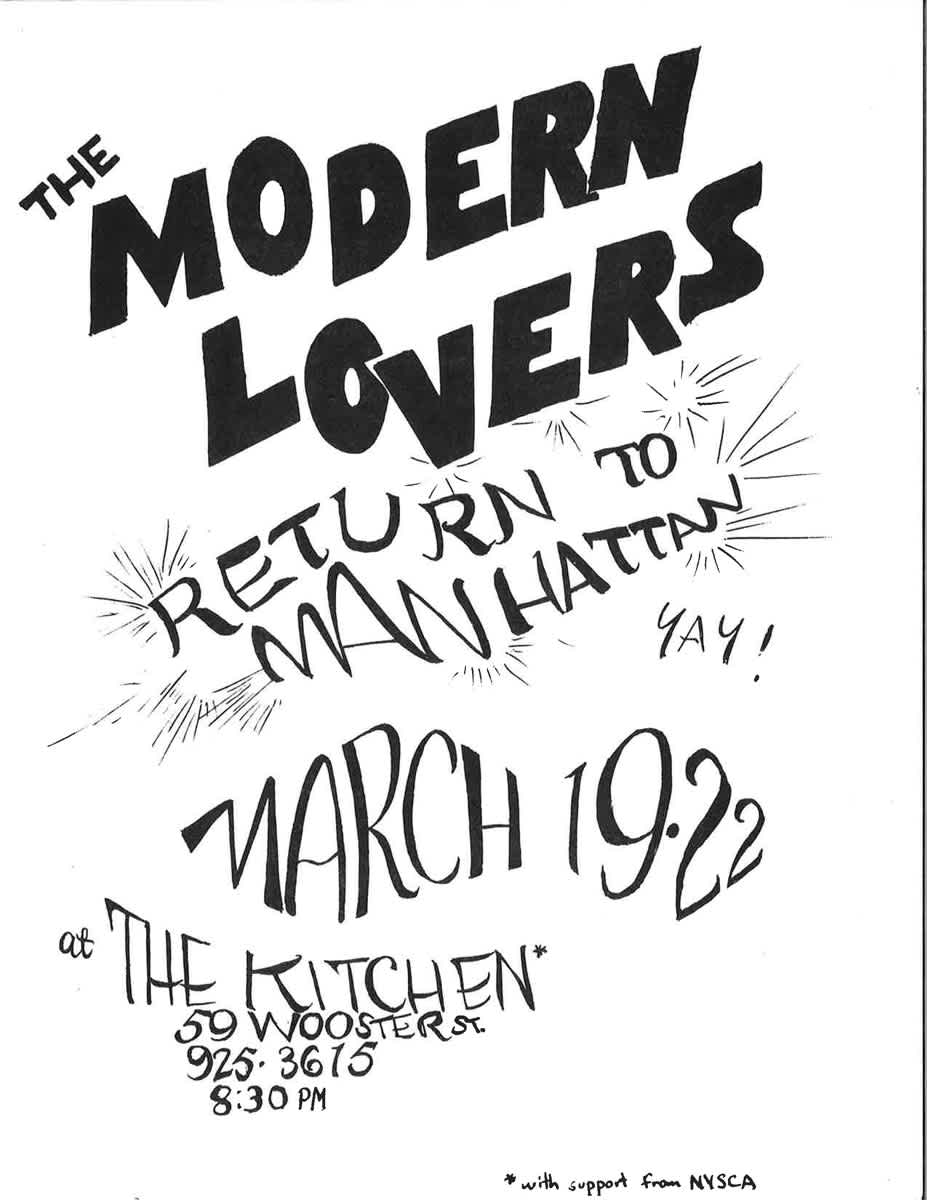

However, a new direction became apparent in Russell’s curating in March 1975, when he booked The Modern Lovers, a proto-punk rock outfit from Boston, to present four nights of Rock and Roll Show. This show forced The Kitchen to revisit the conversation that had been brewing in the adjacent spaces of Mercer Arts Center, when punk musicians and minimalists found themselves performing under one roof. It also exemplifies the boundary pushing between pop culture and art that Stearns and others recall as the defining feature of Russell’s tenure.

Russell first encountered the Modern Lovers when the band performed in New York in January 1974. After the show, he introduced himself to bass player Ernie Brooks. In the following months they stayed in touch. Russell was excited by what he encountered in the Modern Lovers’s music: an approach to the project of sonic deconstruction and abstraction that was different from what was happening in the downtown scene. After meeting again, this time in Boston, Russell invited Brooks and some of his bandmates to record music together. Wanting to collaborate further, Russell and Brooks began planning the Rock and Roll Show.

The show ran for four nights from March 19 to 22. Though the band’s frontman Jonathan Richman performed with his own earnest theatrics, it seems the “show” was not the strict, staged affair that the term often signals. The title Rock and Roll Show differentiated the event from previous performances at The Kitchen that were called names like Natural Sound Workshop, An Incantation, and A New Look at Melody. With its reference to a mainstream genre, the title signified the popular styles Russell intended to meld with experimental sonic structures and the straight-talking, quotidian melodrama Richman and the band delivered. The performances filled The Kitchen’s Soho loft with an unusual blend of audiences, including both Kitchen regulars and Modern Lovers fans. While the show began with a mix of standards and Modern Lovers originals, the second half of the evening featured the band fielding requests, supplied mainly by the fans.

At the time of the concert, some did not consider Richman and his band to be on par with other work presented at The Kitchen. Others remember it as an exciting moment of disruption, bringing in sounds that diverged from the “downtown” music typically presented at The Kitchen. Both The Village Voice and SoHo Weekly News reacted positively to the performances, with the SoHo Weekly News praising Richman’s performance as “good-natured deadpan antics coupled with loneliness and longing that make for a powerful combination … one of those mixtures of wacky profundity and awkward professionalism that New York could use more of.” But the Voice did make reference to the crowd’s mixed reaction, noting that there were “a few remarks that Richman is too facile, false.”

The disapproval of the Lovers’s performance was not solely due to a judgment of artistic merit or musical sophistication. Artists were understandably protective of what many felt was a space for the downtown community. Though several other young alternative spaces presented interdisciplinary and experimental work like The Kitchen did, minimalist composers and experimental performers remained unwelcome in many of the larger art institutions. Now, to some, it seemed that rock—a pop genre that, thanks to its commercial appeal, enjoyed a broad platform and a wider range of welcoming venues—had invaded their limited space.

THE EVENT RAISED QUESTIONS about the kind of institution The Kitchen would become. How broad would its definition of artistic merit and experimentation be? Was this Modern Lovers performance anathema to The Kitchen’s ethos, or an expansion of the exploratory mission established just a few years prior? With time, it became clear that, in staging the Rock and Roll Show, Russell successfully introduced new perspectives into The Kitchen. In an oral history for The Kitchen, Stearns remembers his own impression of the show:

Well, Arthur brought another point of view, and that was pushing the edges of pop music, of popular music. And that raised a whole other argument/discussion that was going on in the community that I think was probably most brought to a head by a performance by Jonathan Richman and the Modern Lovers. By its name alone, it sounds like something straight out of the fifties … They were love songs, four beats, and harmonic notes. I thought The Kitchen walls were going to fall apart. But frankly, I loved it. I was excited about it … Richman just brought a fresh air that I thoroughly enjoyed.

Explaining the impact of Russell booking the Modern Lovers, Lawrence writes, “his invitation to Richman broke new ground because it implied that some forms of unadulterated rock didn’t just have minimalist potential but were actually minimalist already.” In his own music, Russell was distilling sound, balancing plain-spoken generalization and nuanced innuendo, defining his own pop idiom. In booking the Modern Lovers, he made clear that the same fascination directed his curatorial work.

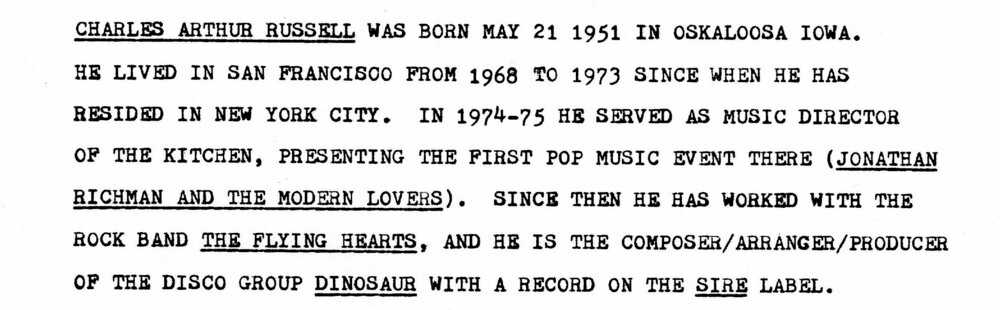

This performance went on to be seen as a significant moment in the institution’s history. Only four years after the show took place, a draft of a 1979 press release for one of Russell’s own performances at The Kitchen, 24 to 24 Music, highlights this moment in Russell’s tenure as Music Director, calling the Modern Lovers concert the first pop music event at The Kitchen. The press release serves as an institutional record characterizing Russell’s legacy as a pioneer who introduced new programming to the organization.

RUSSELL’S ABILITY to defy boundaries of genre and explore pop-musical idioms in his curatorial work points to one of the driving forces throughout his career. In an interview shortly after Russell’s passing in 1992, his partner Tom Lee described Russell’s drive to “make this art-dance hit. He figured there could be a cross reference between dance music and downtown Soho new music.” Russell’s curatorial work at The Kitchen shows that he began working to realize this mission early in his career.

Russell’s curatorial legacy was immediately apparent in the direction of the institution’s subsequent programming. Garrett List, who succeeded Russell as Music Director, remembers a vision they shared, recalling that “we wanted to go from minimalism into popular language, and it was very much in the air at The Kitchen to break down those barriers.” Under List’s direction, The Kitchen became a venue for a widening field of artists, including Jazz musicians in particular. And through the decades until today, The Kitchen has continued to deepen and expand its metamorphic approach to discipline and genre, further revealing the lasting impact of Russell’s programming.