Credits:

Annotated by Studio:Art Grime Destroy (Anaïs Duplan, Folasade Adesanya, Zoe Butler, and Kameron Ray Morton), an anti-disciplinary studio

October 14, 2023

“What it is to sell an idea of your identity…”

– Dave Harris

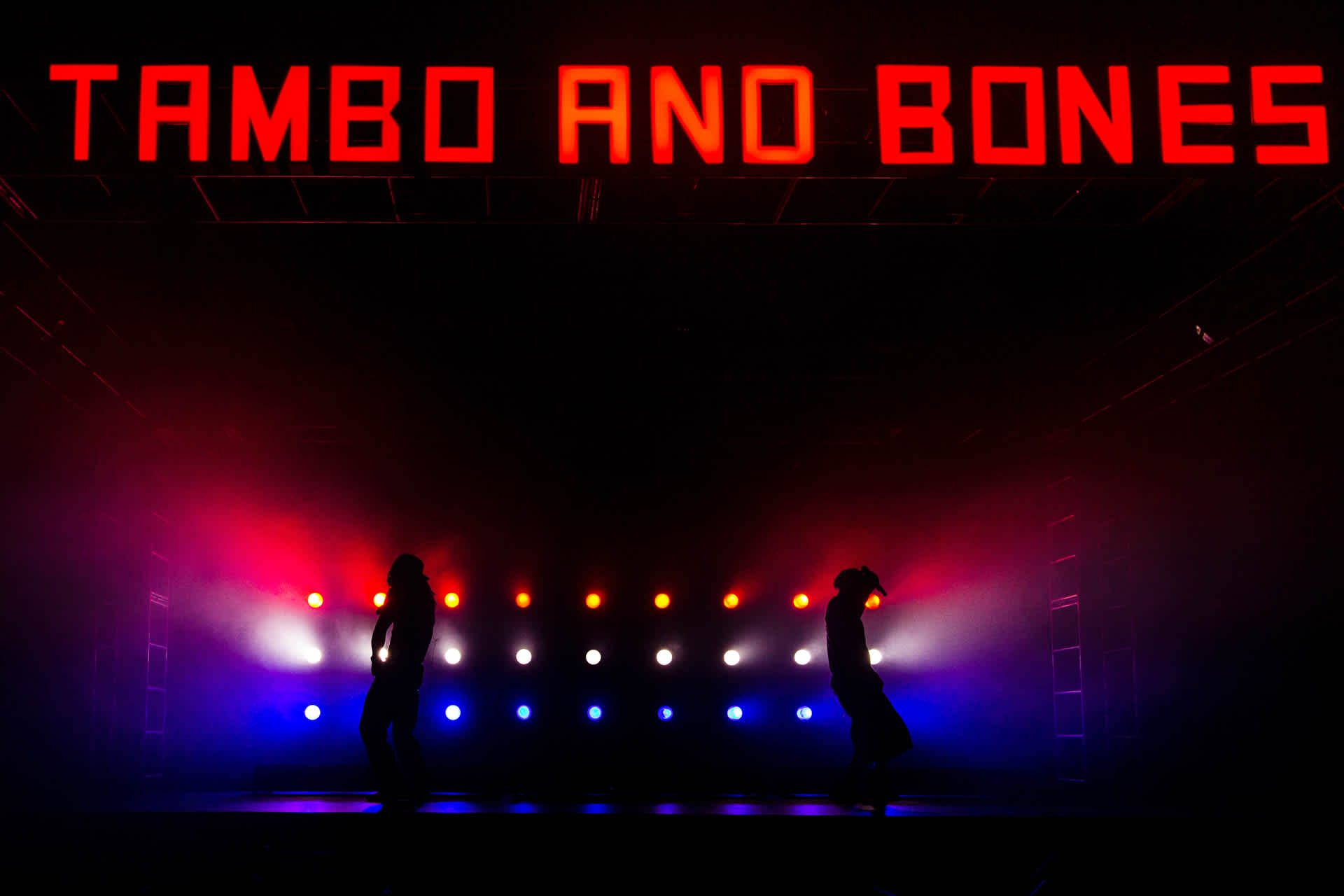

This inquiry is the thread that strings together the following interview with Studio AGD—a collaborative anti-disciplinary studio consisting of Anaïs Duplan, Zoe Butler, Folasade Adesanya, and formerly Kameron Ray Morton—and playwright Dave Harris about his production Tambo & Bones, which premiered at Playwrights Horizons in New York in January 2022. Tambo & Bones is a play with two primary characters that confronts the past, present, and future of anti-Black racism, within the context of a minstrel show. The play has gotten a lot of attention from audiences and press for its representation of minstrelsy, and for its disregard for how many argue Black people “should” perform or depict Blackness. Harris seems to urge audiences to do away with inclinations toward “should haves” in Black performance and to consider instead the glory in the process, the energy exchange between buds on stage, the virtues of experimental theatrical expression for its own sake. How do we release these expectations of how Blackness should be performed–particularly within constructed realities–and just enjoy the show?

This very question can apply equally to Ishmael Houston-Jones and Fred Holland’s performance Cowboys, Dreams, and Ladders, which premiered at The Kitchen in 1984. “I didn’t know how I was supposed to react to it,” Kameron noted when reflecting on the work. Cowboys, Dreams, and Ladders similarly features two primary characters performing as cowboys, whose Blackness and off-putting comedic expressiveness challenges traditional expectations of the Wild West setting. Similar to Harris, Houston-Jones and Holland seem to delight in the beauty of experimental performance, playing within the space that expands when one flips rigid expectations of Black performance on its head—performing for the joy, hilarity, and ease of disregarding how said performance will be received by audiences. The production is interpretive, reminiscent of your favorite improv class whose tone simultaneously elicits confusion and laughter.

The depiction of Black men as cowboys is in itself a subversion of expectations, considering cowboys typically have been depicted as white in American popular culture. History has been reluctant to recall the legacy of Black cowboys on this land. In the mid-19th century, Black men enslaved on frontier farmland, including what is now Texas, Arkansas, and Oklahoma, inherited the responsibility of tending cattle. This experience opened the door for paid work as cowboys after emancipation, as these skilled workers were now in high demand. As Black cowboys entered the workforce, they faced unique discrimination herding cattle across vast and lawless frontier lands, being denied access to white owned lodging and dining establishments and enduring attacks from Indigenous peoples defending their land. As such, Black cowboys developed deep connections and friendships, sustaining community with each other in order to get through the grueling labor, dangerous terrain, and lack of acceptance among Indigenous peoples and white settlers. They depended on each other to survive the wild west. With the introduction of railroad shipping systems in the late 19th century, the demand for this type of work waned, but what remained was a rodeo culture among Black cowboys, further cultivating this camaraderie and friendship among Black men of the region. (1)

Despite the relative lack of recorded history on the subject of Black cowboys, there are some figures whose stories are more widely known. Bass Reeves (1838–1910) is one such figure. Born a slave in Arkansas, Reeves managed to escape to Cherokee, Creek, and Seminole territory as a young adult. (2) He is believed to have served as a soldier in the Civil War before settling down as a farmer in Van Buren, AR. His legacy as a cowboy that persists in today’s popular culture runs counter to his actual profession: he served as the first Black deputy marshal in Arkansas and Oklahoma. He got to know the area well working as a guide, scout, and tracker for white deputy marshals patrolling the area prior to his appointment. As a result, he thrived once he assumed the position of deputy marshal, maintaining his role for thirty-two years and boasting over 3,000 arrests to the delight of white settlers who sought to bring “order” to this lawless region of their settler colony. Reeves thus earned a place in America’s selective memory, punctuated by a statue on the territory he patrolled. It is noteworthy that he did so by performing identity in a way that would appease the state, surrendering to the respectable expectations of his oppressors.

This performance of respectability is expected, given Reeves was playing a role that was typically inhabited by white men. When considering the history of race relations that weaves together American history, it makes sense that placing a Black character in a historically white role would prove problematic, resulting in a complex and fraught legacy. The same can be said of Black minstrel performers.

The practice of minstrelsy began in the early-19th century as a way for white people to perform Blackness with as much degradation as they could muster. This practice would endure in various iterations into the 20th century, when Black folks began to reclaim the space as their own. Despite the legacy of violent stereotypes associated with the caricatures of minstrel shows, Black artists who were already “living on the margins of respectability” participated in self-effacing acts, some even donning blackface. William Henry Lane and Thomas Dilward were the first African Americans to perform in minstrel shows in the 1840s. This made way for turn-of-the-century performers including Bert Williams, George Walker, and Bob Cole to sell out shows in Harlem and Manhattan, at venues like the famed Black-owned Marshall Hotel. These performers found inspiration and collaboration with other talented Black creatives who gathered at this treasured venue, together making up what has been referred to as the Marshall Circle. But they did not do so solely for the fun of it: they made their living by performing for unsuspecting white audiences who remained clueless to the subtle yet socially aware messaging that these Black artists often injected into their shows. Poet and novelist Paul Laurence Dunbar was known for criticizing colorism, colonial capitalism, and class politics in his contributions to minstrel shows in the first decade of the 1900s. This became a balancing act of appeasing white audiences while boldly pushing a political agenda that intended to speak directly to Black audiences. (3) Many Black patrons at the time criticized what they perceived as the performers’ lack of concern for respectability in these performances—criticism similar to that leveled at contemporary performances like Tambo & Bones.

Both Tambo & Bones and Cowboys, Dreams, and Ladders prompt us to consider: When do we stop concerning ourselves with the white gaze? The history of Black men as cowboys (performing whiteness) & minstrel performers (performing Blackness informed by whiteness) is inherently problematic and delegitimizing, while it also opens up a space to play and experiment with new conversations. How do we reckon with a performance of Blackness that exists in an artificial space that was not intended for us? How do we continue to take up space where we’ve been historically excluded? With his creative choices and throughout the following interview, Harris argues for a more holistic interpretation of Black productions that leaves space for Black folks to saunter in the shapelessness of expressive performance without concern for respectability.

— Folasade Adesanya

Interview Clip

Excerpt from January 2022 interview with Dave Harris and Studio AGD, featuring Anaïs Duplan and Harris.

Kameron Morton (KM): I grew up in Fort Smith, Arkansas. The people there like to think of themselves as the true Wild West. It’s right on the border of Oklahoma. They’re famous for this judge in the late 1880s whose big shtick was hanging people. Hanging Judge Parker.

Anaïs Duplan (AD): Hanging Judge Parker?

KM: Hanging Judge Parker. It’s very catchy. In Cowboys, Dreams, and Ladders by Ishmael Houston-Jones and Fred Holland, they’ve got that guy hanging in the back, who they then take down. I was like, I guess this does feel like the Wild West to me. Specifically as someone who grew up not far from a recreated gallows.

I have always felt hangings were more representative of the Wild West than cowboys. This is what happens when you grow up in Fort Smith, Arkansas. Your town history is mostly limited to the late 1880s, when the government sent in a judge who was supposed to bring law to our lawless land. If you’ve read the 1968 novel True Grit by Charles Portis, you’re already familiar with Judge Isaac Parker. His gallows still grace the banks of the Arkansas River, about one-and-a-half miles from my old high school, within sight of a monument to Bass Reeves. (4)(#credits) He sits on his horse, rifle pointed at the sky, a hound dog walking alongside him. He’s got a cowboy hat and spurs, a costume that would fit in well with the clothes worn by Houston-Jones and Holland at the beginning of Cowboys, Dreams, and Ladders, when they do their gun and rope tricks and dance how cowboys do (according to choreographer Agnes de Mille). I don’t know that Bass Reeves was the type to dance, though.

Dave Harris (DH): Everyone’s trying to make a movie about Bass Reeves right now.

KM: He’s become very popular in the last couple years. Of course, for me growing up it was like, Oh, we’ve got this Black cowboy. It’s exciting. He exists, here’s a statue. I’ve heard about him my whole life. What I always thought was interesting is, in Fort Smith, the angle was very like, He’s a cop who brought people to justice. Because he was a marshal, he worked for Hanging Judge Parker. He was bringing people in from Oklahoma to be hanged.

DH: Oh, he worked for Hanging Judge Parker?

KM: Connections, right? There was that historian a few years back who was like, Here’s my argument that Bass Reeves is the basis for The Lone Ranger (1949). (5) Which is very cool, but I’ve always seen Bass Reeves as this intense cop figure. One of the things he’s famous for is arresting his own son for murder.

AD: My Lord.

KM: This is the only Black cowboy I’ve ever heard of. His legacy is very interesting and complicated. Born a slave, escaped, never learned to read but spoke three languages and then worked with Judge Parker to bring law and order to the lawless Wild West.

DH: Sony’s trying to make a movie about him now with [actor] Regé-Jean Page.

KM: The Bridgerton guy.

DH: Everyone’s on Black cowboys right now.

AD: Concrete Cowboy [2020 film].

KM: Oh, Idris Elba [actor].

AD: Where is Concrete Cowboy set? Chicago?

KM: The film was in Philadelphia.

DH: The Harder They Fall [2021 film]. That’s what I was thinking of. It’s another Netflix one. Elba is the cowboy.

KM: He was floated, not for Sony’s Bass Reeves project, but for a project somebody else is trying to do about Bass Reeves.

By definition, a cowboy is a man, usually on horseback, who tends cattle. Reeves did not tend cattle, though he was on horseback. Reeves was a cop. A “deputy marshal” if we’re being specific, but a cop is a cop. There’s a video dropped into the middle of Cowboys, Dreams, and Ladders of what looks like a rodeo cowboy to me, dressed fancy and doing tricks. I imagine Reeves could do all of that, and if he’d had access, he would have worn fancy clothes like the man in the performance. In between learning three languages and memorizing arrest warrants because he couldn’t read and having kids with his first wife, Reeves spent time getting good with his horse. He would have had to, in order to be good at his job. So good, in fact, that he even murdered someone he was supposed to arrest like cops seem to—a charge for which he was acquitted, of course, after being represented by his good friend William Clayton (whose house I’ve visited) and judged by his friend and employer Hangin’ Judge Parker. I can easily imagine Reeves quoting Gene Pitney’s 1962 song, “The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance.” Pitney may be the one credited with it, but I’d bet that Reeves said it first: “the point of a gun was the only law that [man] understood.” —KM

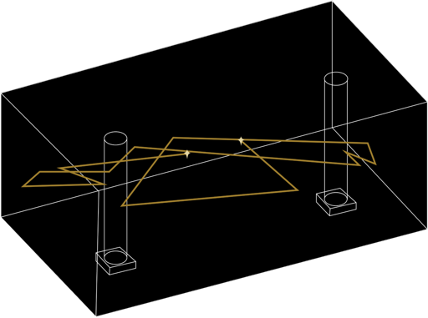

Zoe Butler (ZB): I’m coming from a less historic angle and more of a movement, gesture, and object base of thinking. I responded to Cowboys, Dreams, and Ladders and this playfulness between the characters, and the way they acknowledge their environment through the ricocheting bullet that moves through the stage.

There are these scenes where they’re playing, shooting, and one person will be far behind one of the characters who’s shooting and he’ll shoot forward and the bullet will ricochet off an invisible surface. There is no bullet. You see his homie fall on the ground as though he is being shot in this opposite direction, where it wouldn’t make sense.

I was interested in the relationship between how we acknowledge the container of the performance. The relationship between this piece and all the other cowboy-themed pieces that you have offered as well. Thinking about your process, Dave, how do the characters in Tambo & Bones resist the fact that they’re characters? How do they resist the environments that they’re in?

DH: Tambo & Bones started from two separate obsessions.

The first was with the history of minstrelsy, which was in some ways the birth of Black American performance, and Black artistic capitalism, which is to say, the selling of performance to an audience. I was thinking through the distinct craft of minstrelsy, and the ways in which minstrelsy is bemoaned and demonized when we look back on history.

But in its time, minstrelsy took so much talent and skill to do. There were many Black performers, who were some of the greatest performers of history, who trafficked in it and found a certain level of joy and freedom through the performance of it. I found that lens fascinating and surprising—that power dynamic between Black performer and white audience, and what it is to sell an idea of your identity, over and over again, to an audience who will pay you lots of money for it.

DH: This then tied into the second obsession: my history with spoken word and poetry slam, which was a very important step in my growth as a writer. But at a certain point, the craft of it became repetitive and manipulative. I was writing the same police brutality poem over and over again for an audience who would be full snapping and crying, and then I would feel like I’d done a good job and written well. But I wasn’t learning how to grow as an artist, I was learning how to perform vulnerability. And it was working. Writing and telling that type of struggle story got me scholarships, fellowships. It moved me forward so much.

So with Tambo & Bones, I was interrogating capitalism and art, what it is to still be in a cycle, performing identity for a white audience, and how that affects your ideas of yourself and your orientation as an artist. That became very complicated.

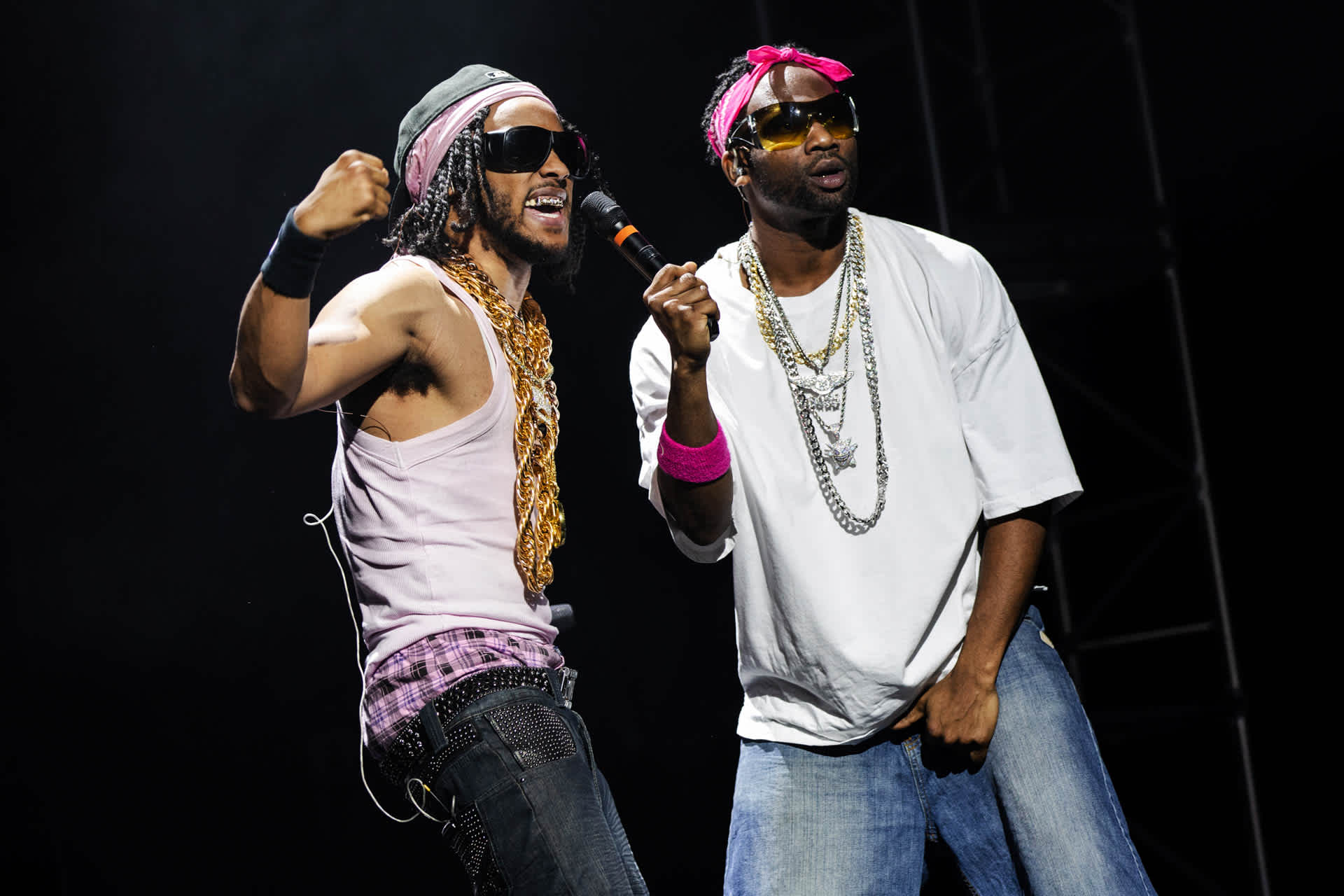

“Tambo” and “Bones” are two minstrel archetypes in the canon of minstrel performance. In my play, they’re two characters who come to discover that they are stuck in a perpetual Minstrel Show. On top of that, they’re struggling to get money. They keep asking the audience for quarters and putting on these different acts for them, trying to get the audience to pay them, because all they want is money so they can rise out of the fake-ass pasture they live in.

Eventually they come to realize that the reason that they’re stuck in this pasture is not because white people are the audience, it is because of the playwright who wrote them there. Then they go into the audience, grab the playwright, kill the playwright, and rip him apart. His stomach is full of quarters, which is what they’ve been after.

DH: They get the quarters, they get the money, they get the mechanism of change, but they come to find that they’re not any happier than they were before they had the money. They’re like, Okay, how do we get to the next step? We should become rappers and make millions of dollars through that.

The second part of the play is a rap concert in the theater, where they’re putting on this giant spectacle for this audience. They have songs, they have a T-shirt cannon, they have all the wealth that Black performance can get you. Come to find out they’re still not as happy as they thought they would be. They’re still trying to fill some void inside of them.

DH: One of them discovers maybe the source of this void is the essential power dynamic between Black performer and white audience. And liberation from that dynamic will fill the yearning inside of them. The solution? I’m going to invent robots that can commit white genocide and then we’ll be free.

So, the third part of the play takes place 400 years after the white genocide, where now Tambo and Bones are no longer defined as Tambo and Bones. They’re the names of the actors playing the two characters, and they’re speaking to an imagined audience full of Black people at the historical celebration, where they celebrate the white genocide that got them here. They perhaps find—or perhaps don’t find—that they are freer than they were before.

AD: I’m impressed.

DH: The robots are played by white actors. White actors who look basic and white. They end up becoming the oppressed robot population of this future without white people.

AD: This takes many twists and turns.

DH: It’s a crazy one.

AD: When Zoe was talking about the strange rules of the space of Cowboys, Dreams, and Ladders, I was thinking about the opening of Tambo & Bones where, as an audience member, I was trying to think through the rules of your set, and how the space that Tambo and Bones were in was simultaneously real and fake. I wonder if you could talk through that a bit, the spatial construction.

DH: That’s my favorite thing about theater, that everything is artificial, including all the identity constructs that we build into it. When I was writing these spoken word poems, I was in some ways performing a rehearsed idea of identity, which removed me from any idea of truth beneath it. Not that I necessarily think there was a truth beneath it.

For theater, these two characters Tambo and Bones exist in a set that’s described as a “fake-ass pasture.” There’s a pastoral painted cloth behind them that has a sunset, a very fake looking sun, and some cardboard trees and some astroturf grass cutouts. For these characters who live there, it’s home. They haven’t necessarily realized that they're living in something that’s completely constructed. The first act is them, through currency and confrontation, learning that everything around them is fake. Maybe they can strive for something better. But each step at “better” still is built on the same kind of lie.

In terms of the space, how do we create something that feels appealing enough that we can understand why someone would want to believe it was real?

When you touch a tree and it falls over, suddenly your whole identity collapses. That becomes a relationship with the audience too. Many people want to believe theater is true and people want to believe identity is truth. There’s so much room to play once you accept that everything we’re looking at is a lie, and everything we’re looking at is manipulated in some way by the artist creating it. That, for me, is the space that I like to play in.

Is the current moment the same as every single other moment that passed before us? In terms of creating this play, it was, for me, something that could hold potentially all of history. All the reality of present-tense bodies, audiences in the chairs, and the two characters on stage. They’re wearing a pastiche of minstrel-time outfits, but all of their language is based on how someone might talk today, with some idioms from forty years ago. How do we collapse time?

AD: The way that Tambo and Bones move around the space feels like it’s an embodiment of the time they’re in and the people they are. How did you coach them? What were you looking for?

DH: It was a combination of clowning. Clowning is also based in minstrel history. George Walker and Bert Williams were a minstrel duo who started in blackface performance. Eventually George Walker started refusing to wear blackface, but Bert Williams kept wearing blackface. There was a quote in one of the minstrel history books I was reading, that was essentially to the effect of him saying, There’s something liberating in playing this clown.

For Tambo and Bones, it was thinking about how we draw from this history in a way that unlocks how your own “clown” might exist today. The actors I work with will be like, This is the most fun I’ve ever had on stage. That came across in some of the interviews with old Black minstrel performers too.

We get very tied up in what we think Black people should be doing on stage. Tambo & Bones is like, how do we pull from the whole history of Black performance and pull from our own impulses and then create something that, no matter what we’re getting from the audience, is fun and pleasurable for us.

Ultimately that is what I care about the most: that there’s pleasure in our process and in our product. Then an audience can bring what they need to it. Pleasure is what carries the show and carries the actors. As long as we have that, then anyone’s response is welcome, even if I’m exhausted by some of them. We had some Black people being like, This is not how Black people should be on stage.

AD: Respectability people? The respectability crew showed up?

KM: This made me think a little bit about A Strange Loop (2019), that musical [written by Michael R. Jackson]. One of the big running themes is the main character is a guy writing a musical. His family keeps wanting him to do a musical like Tyler Perry’s. At one point, he does a Tyler Perry musical and then flips it. It’s cool. It’s like, What do we expect from performance? And for me, watching Cowboys, Dreams, and Ladders, I have no experience with experimental performance. I was confused because I didn’t know how I was supposed to react to it. I kept feeling I wasn’t having the right reaction. I wanted the right reaction and that’s not the point of theater or performance.

When I reached the end of Cowboys, Dreams, and Ladders the first time, I was at a bit of a loss. I didn’t know what I was supposed to think, or take away from it, or conclude. There were these two men sort of talking and playacting cowboys, there were wind-up toys, there was footage of a “real” cowboy (whatever that means), a woman came on stage and danced. The first thought I had was that the whole thing did feel like a dream. Disjointed, and a little strange, leaving me confused and off-center. I was thinking about the choreography in the musical Oklahoma!, and a few other half-formed thoughts. After a few moments of trying to parse together some notes, to come up with how to interpret what I’d watched, I realized I was homesick. I didn’t know where it came from. I’ve never liked the Wild West part of my hometown. I’ve never defined it in that way, despite the town tourism board’s best effort to make Fort Smith synonymous with a romanticized cowboy paradise. It didn’t occur to me to think of the performance as something personal to me, not until some unconscious part of myself bubbled up a longing for the Arkansas river, even if the gallows are right there next to it. That’s what Cowboys, Dreams, and Ladders gets right that Fort Smith gets wrong. Those hangings shouldn’t be front and center, even if they’re omnipresent. They should be in the back. A ghost, or a haunting. Just enough to make me miss a place I’ve never cared for because finally, someone was showing it to me the right way. — KM

DH: That’s why it’s liberating to watch something that can baffle you and be itself.

ZB: It’s making me think about the range of ways that people react to a social script being broken. How do you feel like people responded to Tambo & Bones? What was the feedback that you were getting from friends and families, and how do you think it’s informing how you move forward?

DH: It was different. Every show was different every night. What I find both exhausting and fun about the whole thing is that it’s the same exact conversation we’ve been having about Black performance since minstrelsy. The parameters around how we think Black people should exist on stage in front of other people, it’s the same. Billy Kersands, who was a big Black minstrel performer, has a joke book of his minstrel jokes. One of the jokes was like, Where does the Black man go when he hurts his knee? To Africa, where the knee grows. That’s funny. I know there’s many people who will be like, That’s fucked up. You can’t say that.

DH: Doing Tambo & Bones, I feel connected to this legacy of satire and comedy. We have all different metrics of what’s funny or not. We all think that we’re right about what’s funny or not. At our very first performance, we had a white audience member who was mad at the genocide that the show ended with, and he went into the lobby and started destroying shit. He flipped a table, he broke all the hand sanitizers. He went to the street and threw a ceramic planter into traffic.

AD: In some ways, there’s overlap between the minstrel and the cowboy, but in other ways humor works around those figures very differently. We expect the minstrel to be Black. White people would pretend to be Black, which subverts the expectation that minstrels are Black, and is additionally funny because Black people are categorically funny. The cowboy is triggering in a different way. Dave, if you had to work with this figure of the Black cowboy, where would you start? What would you want from that?

DH: I went through an intense, probably fourth grade, cowboy phase where my mom and I were watching every Clint Eastwood movie. We had them all on DVD. We watched The Good, Bad and Ugly (1996) at least seven times. When thinking about cowboys, I’m like, What’s the personal pleasure that I find in cowboys?

I will say one of the most interesting cowboy movies I’ve seen is Cowboys & Aliens (2011). It’s a very flawed movie, but the premise was fun. They’re in this physical space and physical time that is its own time capsule. The movie doesn’t become about the history of cowboys, it becomes about how we can create our own uniqueness in this space.

Why don’t we create history in our own image, or in an image that expands possibilities?

BIOS

Anaïs Duplan is a trans* poet, curator, and artist. He is the author of book I NEED MUSIC (Action Books, 2021); a book of essays, Blackspace: On the Poetics of an Afrofuture (Black Ocean, 2020); a full-length poetry collection, Take This Stallion (Brooklyn Arts Press, 2016); and a chapbook, Mount Carmel and the Blood of Parnassus (Monster House Press, 2017). He is a professor of postcolonial literature at Bennington College, and has taught poetry at The New School, Columbia University, and Sarah Lawrence College, amongst others.

As an independent curator, he has facilitated curatorial projects in Chicago, Boston, Santa Fe, and Reykjavík. He was a 2017-2019 joint Public Programs fellow at the Museum of Modern Art and the Studio Museum in Harlem, and in 2021 received a Marian Goodman fellowship from Independent Curators International for his research on Black experimental documentary.

He is the recipient of the 2021 QUEER|ART|PRIZE for Recent Work, and a 2022 Whiting Award in Nonfiction. He was also awarded a Black Visionaries Award by Instagram and the Brooklyn Museum in 2022. In 2016, Duplan founded the Center for Afrofuturist Studies, an artist residency program for artists of color, based at Iowa City’s artist-run organization Public Space One.

folasade adesanya is a studio manager at Studio AGD and a blooming neuro/quirky queer agender writer, curator, and independent scholar. Their work is deeply aligned with their spiritual practice, with projects that source from queer Afro-diasporic archives, oral histories, and inherited knowledge. Their current projects include intuitive prose poetry; speculative non/fiction that pieces together Black QTGNC care communities in pre-Civil Rights eras; and unspooling the stories of her lineage. She has been published in MN Women’s Press, and is currently editing her first zine titled sacred is the place you touch, to be published in early 2024.

Folasade founded The Black Syllabus in 2019. They are also an emerging flower farmer and beekeeper hoping to grow toward homesteading in the near future. She was born and raised in the Bay Area, currently rooted in the Twin Cities with her cat Parsley.

Zoe Butler is a New Media Performance Artist who uses abstraction to explore the relationship between material culture and embodiment. Butler’s recent work engages with both personal and museum archives to explore artifacts that resist histories of domination. Her work often discusses the way that power sculpts our visual and lived realities through mediums that range from computer-animated films to wearable technology-assisted performances. Her recent work takes an interest in the deterioration of objects over time; whether reflected in the decay of family VHS tapes or the erosion of slave ship wreckage. Butler’s practice responds to the materiality of artifacts to embrace the abundance of counter-histories and to encourage people to see themselves beyond the representational. Butler is a 2023-2024 Fulbright Research Fellowship recipient, affiliated with The University of the West Indies, Saint Augustine. She is undertaking research with the Department of Creative and Festival Arts, in tandem with a film premiering in summer 2024. Her work has been performed and screened by institutions such as The National Museum of African American History and Culture, The Gene Siskel Film Center, High Concept Labs, and Ars Electronica.

Kameron Ray Morton is a writer whose fiction has appeared in Eclectica Magazine, Permafrost Magazine, and Valparaiso Fiction Review, among others, and their flash fiction “Broken” received Honorable Mention in Coastal Shelf Literary Magazine’s The Ceiling 200 Contest. They received their MFA in Writing and Literary Translation from Columbia University and currently work as a Young Adult Specialist at the New York Public Library – High Bridge Branch. Find them on Instagram @tallsoyflatwhite.

FOOTNOTES

(1) See: Because of Them We Can Staff, “ Here’s Everything You Should Know About the Story Behind Black Cowboys.”* Because of Them We Can*, November 29, 2022. https://www.becauseofthemwecan.com/blogs/culture/here-s-what-you-need-to-know-about-the-history-of-black-cowboys; Katie Nodjimbadem, “The Lesser-Known History of African-American Cowboys.” Smithsonian Magazine, February 13, 2017. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/lesser-known-history-african-american-cowboys-180962144/.

(2) Art T. Burton, “Reeves, Bass.” The Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture, https://www.okhistory.org/publications/enc/entry.php?entry=RE020.

(3) See: Minstrel collection, 1863-1928, "Biographical/Historical Information," Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, Manuscripts, Archives and Rare Books Division, https://archives.nypl.org/scm/29969; Dorothy Berry, "When Black Celebrities Wore Blackface," JSTOR Daily, August 12, 2020. https://daily.jstor.org/when-black-celebrities-wore-blackface/; Jonathan Daigle, "Paul Laurence Dunbar and the Marshall Circle: Racial Representation from Blackface to Black, African American Review Vol. 43, No. 4 (Winter 2009): 633-654. https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/41328662.pdf.

(4) Bass Reeves is a native Arkansawyer who was born into slavery in 1838. He escaped during the Civil War and went on to become the first Black deputy U.S. Marshal, working mostly in Arkansas and so-called "Indian territory." During his career, he recorded 3,000 arrests.

(5) The theory is introduced in the book Black Gun, Silver Star: The Life and Legend of Frontier Marshal Bass Reeves by Art T. Burton (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2022). The Arkansas Encyclopedia entry doesn't mention it but Britannica does. See Editors of The Encyclopedia Britannica, “Bass Reeves,” in The Encyclopedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/biography/Bass-Reeves.