Credits:

Lilly Cao, Summer 2020 Curatorial Intern

August 12, 2020

One night in 1979, at the end of an evening of performances, ten artists stood in a line across The Kitchen stage facing a packed theater audience. The performer farthest left held a large cardboard box. Setting the box on the floor, he opened it and removed a smaller cardboard box before passing it to the performer next to him. This artist examined the box curiously, set it down, and proceeded to do the same. The box, which eventually revealed a jar, and then a smaller jar, and then a pill bottle, finally reached the last performer in line, who removed from it a small, deflated balloon. He blew into it, revealing the word “FIN” painted across its surface; the audience erupted into applause, and he released the balloon, sending it whistling into the audience to laughter and cheers.

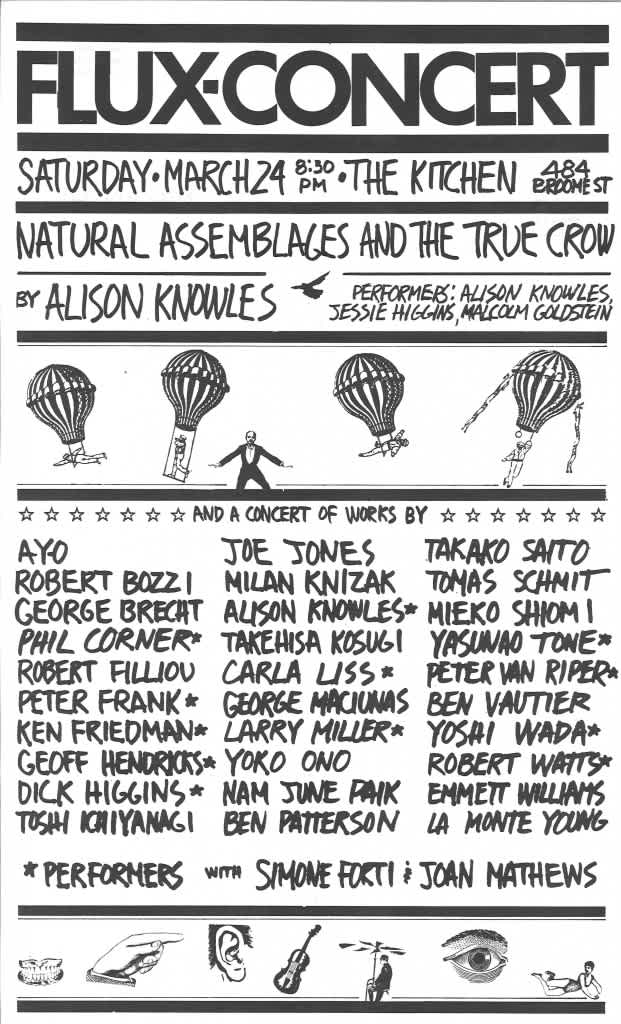

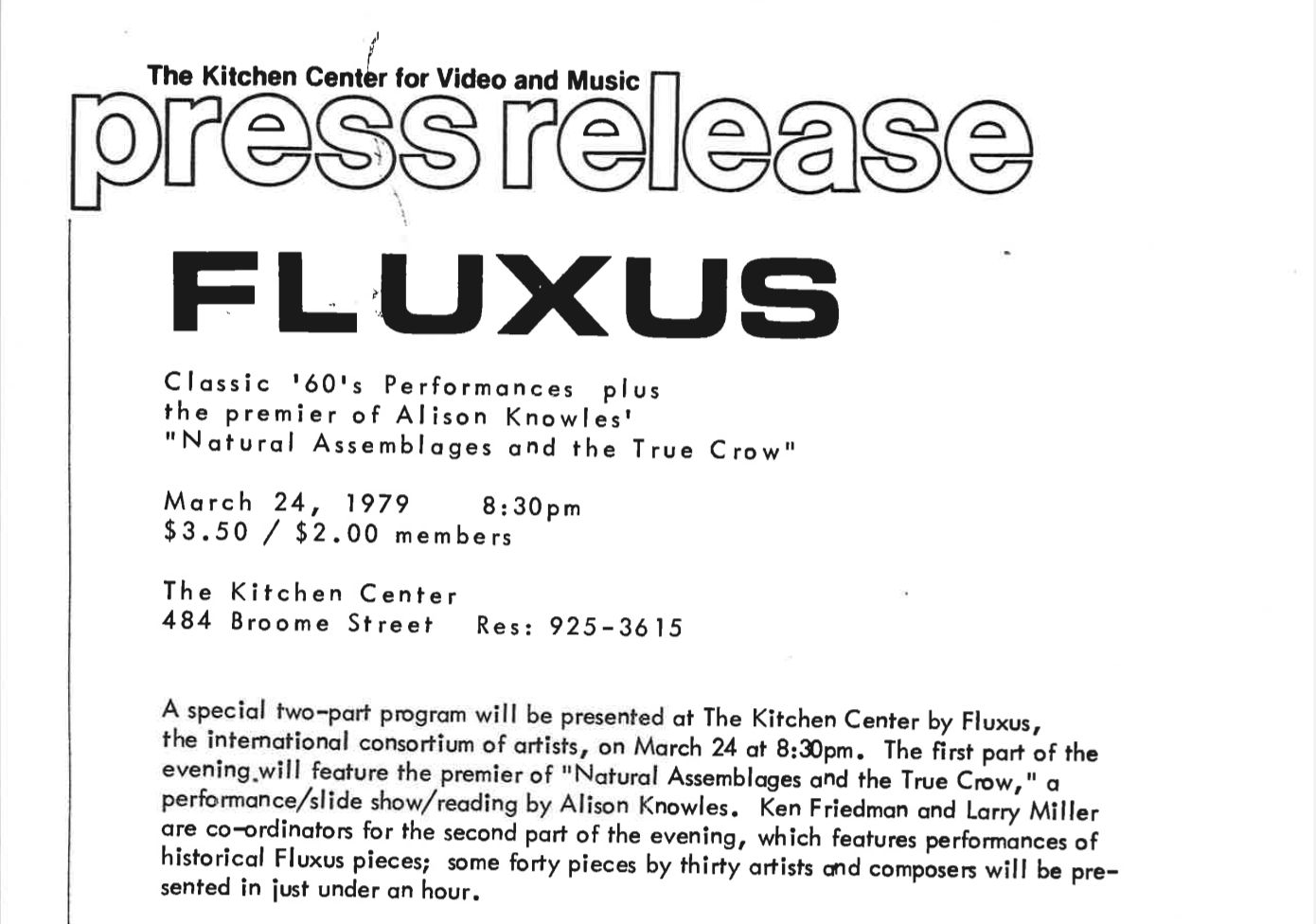

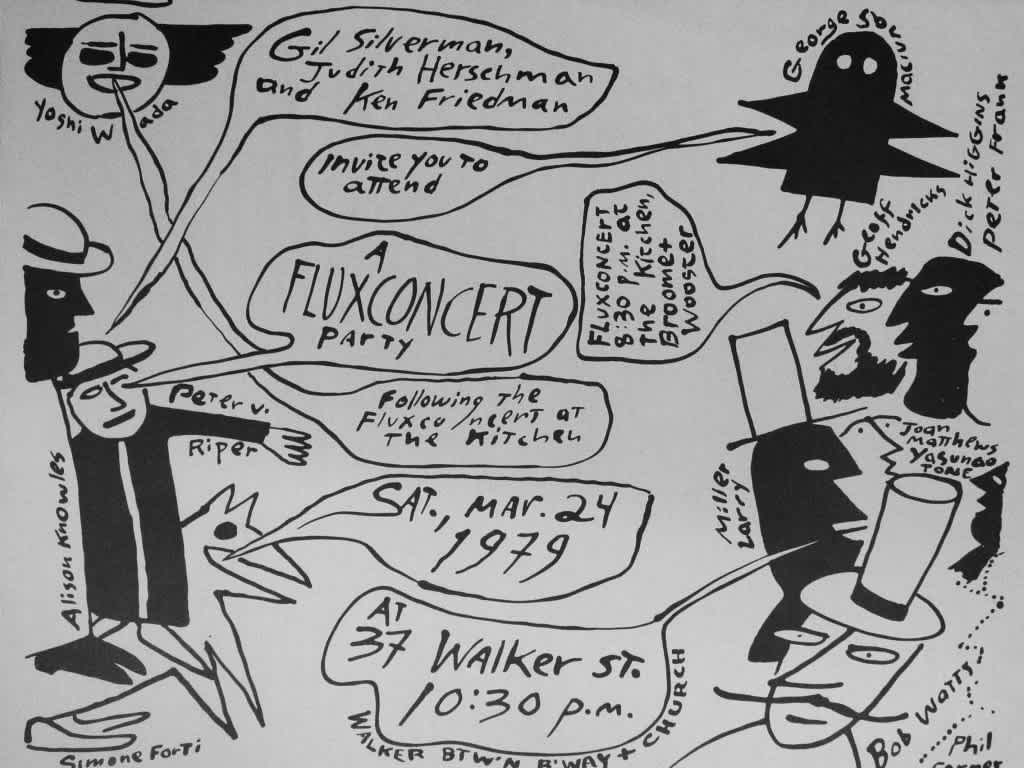

Thus concluded Flux Concert, a night of over thirty performances by prominent Fluxus artists hosted at The Kitchen’s location at the corner of Broome and Wooster Streets (where it was located from 1973–1985). The evening began with an individual performance by Fluxus artist Alison Knowles but was followed by the group concert, marketed as a survey of important Fluxus works from the past two decades. Each performance consisted of a one to two minute “event,” a quintessential Fluxus art form invented by George Brecht and defined by the acting out of short scripts or “scores.” Coordinated by artists Ken Friedman and Larry Miller, the concert included events written by Brecht, George Maciunas, Yoko Ono, Nam June Paik, La Monte Young, and many more, with twelve artists including Knowles, Yoshi Wada, and Yasunao Tone performing them. Many of these artists, including those who wrote and those who performed the scores, had worked with The Kitchen in the past and would continue this relationship for decades: Simone Forti, for example, would perform or show work at The Kitchen no fewer than eight times between 1975 and 1995. Paik would return a similar number of times throughout the early ‘90s.

Yet the relationship between the Fluxus group and The Kitchen was decidedly more complex than a smattering of return performances by several individual artists. Fluxus itself famously defies categorization: art historian Owen Smith has described the movement as “by nature anti-essentialist,” characterizable as an international array of social connections rather than as a core aesthetic or ideology. The boundaries of when Fluxus “ended” and who was explicitly a “Fluxus artist” are therefore impossibly nebulous. Though artist George Maciunas was considered the founder of Fluxus, its participants often organized their own events and artworks independently of him, and claims of “membership” to the group were often contentious due to disagreements among artists and with Maciunas himself. With the Flux Concert taking place after Maciunas’s death in 1978, and therefore—by some accounts—after the termination of Fluxus, The Kitchen’s affiliation with the group appears similarly difficult to define. Notably, Flux Concert’s press release describes the show as “largely historical” and speaks of Fluxus in the past tense, intimating that, at least officially, the group’s activities were considered over. Yet the concert is itself proof that the artists continued to produce work together, and Friedman’s bio in the same document conspicuously states that Friedman “has been involved in Fluxus activities since 1966,” suggesting that the group’s output was still ongoing.

Fascinated by these connections between The Kitchen and this form of art, I chose to investigate them further using three events from the concert as starting points: Piano Piece for David Tudor #2 (1960) written by La Monte Young and performed by Yasunao Tone, A Radio Music (1963) written and performed by Tone, and One for Violin (1962) written by Nam June Paik and performed by Larry Miller. Each performance serves as a lens into a different aspect of The Kitchen’s relationship with Fluxus, from the group’s artistic influence on early Kitchen curators and performers to its artists’ direct collaborations with The Kitchen in later years.

The eigth piece shown at Flux Concert, Piano Piece for David Tudor #2, came from Young’s Compositions 1960 series and was performed by Tone. The event score reads:

"Open the keyboard cover without making, from the operation, any sound that is audible to you. Try as many times as you like. The piece is over either when you succeed or you decide to stop trying. It is not necessary to explain to the audience. Simply do what you do and, when the piece is over, indicate it in a customary way."

As Young was an instrumental early contributor to Fluxus, this work is demonstrative of the movement’s interests in many ways. In her seminal book Fluxus Experience, art historian Hannah Higgins suggests that John Cage’s theories on experimental and circumstantial music composition were foundational to the Fluxus movement. Like Cage’s music, Fluxus events were open to the musicality of chance sounds and to the artistic value of prosaic events more broadly. In Piano Piece for David Tudor #2, the instructional format of the event score encouraged variation at each performance, and while the noise of the keyboard cover opening was deliberately inaudible, it was nonetheless portrayed as music. This Cage-inspired challenge to the boundaries of music and art was common to many Fluxus performances, as was the emphasis on the senses—tactile and auditory—as a means of connecting with the world. To the artists of Fluxus, interacting with instruments in non-prescriptive ways was simply another way of knowing them. Higgins considers this aim of sensory exploration the “ultimate goal of Fluxus”—one that is observable not just in Tone’s careful adjustment of the piano cover but in other Fluxus and Flux Concert works including One for Violin and Piano Work (1970) by Philip Corner.

Outside of the realm of Fluxus, the work of Young and other Fluxus composers played a significant role in shaping the American avant-garde music scene. One artist Young influenced directly was Rhys Chatham, The Kitchen’s first Music Director from 1971–1973 (he returned to the role from 1977–1980). Chatham studied under Young and was a member of his group The Theater of Eternal Music in the early 1970s. In an interview with BOMB Magazine, he cited Young as an important inspiration. This connection extended to shape The Kitchen’s early music programming: many of its earliest performers were friends of Chatham’s from within the New York music community, including Young and Tony Conrad, another composer involved with Fluxus. Moreover, the interconnectedness of the downtown music scene bred crossovers of Fluxus ideas and other contemporary experimental practices, bringing artists to The Kitchen who were influenced by Fluxus even if they were not considered part of it. Thus, in these early years, the relationship between Fluxus and The Kitchen stemmed not only from Chatham’s personal connection but also from the group’s larger artistic impact in New York City at the time.

Tone's A Radio Music was performed later that night, by the artist himself. To start the piece, he knelt on the stage and opened a briefcase filled with transistor radios. He then began meticulously tuning them until they all reached the same station. Finally, he resealed the briefcase, bowed, and exited the stage.

As was characteristic of other Fluxus art at the time, the music generated by the radios was entirely circumstantial. Prioritizing process over program, Tone produced a melody that fluctuated freely with the tuning process, relinquishing control in a way that reflected the open-ended nature of the typical Fluxus event. To remove this control also served to undermine the traditional authority of the artist, a central tenet of many Fluxus works. However, this artistic philosophy gained new meaning when applied to a technology like radio, which, unlike circumstantial environmental sounds, outputs noise that is produced or curated by other people. This peculiarity further de-platformed the artist by distributing his authority to multiple other artistic producers, most of whom were unwitting and unknown.

In fact, A Radio Music was unique in its use of electronics at all, since this technology was pioneered as an artistic medium by several important Fluxus artists but not a universal interest of the group. Most of the events at Flux Concert primarily utilized traditional instruments or prosaic materials such as a piano, violins, paper, cellophane, or water. That evening, A Radio Music thus singularly represented the work of the multiple artists in Fluxus who were highly active at the intersection of art and technology. Paik, for example, was both a prominent Fluxus member and widely considered the father of video art, and he would debut many video art works within The Kitchen’s doors. Shigeko Kubota, who was briefly involved with Fluxus, was an important early feminist video artist who would collaborate repeatedly with The Kitchen. Tone himself was an Fluxus artist and composer who would perform his process-based electronic compositions at The Kitchen throughout the 70’s and 80’s. By virtue of their shared interest in these technologies, these Fluxus artists became more closely involved with The Kitchen than some others due to The Kitchen’s own founding investment in the electronic arts.

Tone would return to The Kitchen several times after Flux Concert, making him part of a long list of Fluxus artists who would perform at The Kitchen on multiple occasions within their lifetime. Many of his later works continued to interrogate the relationship between music, chance, and the processes of production as he did with A Radio Music, and he became particularly well known for manipulating or damaging audio CDs to alter the sounds emitted. In a similar vein, his work Molecular Music, which was shown at The Kitchen in 1989, transformed ancient Chinese characters into an accumulation of images, projected them onto a screen, and then used photosensitive oscillators to create music from them. Besides embracing process, this work and others exemplified what fellow Fluxus artist Dick Higgins called “intermedia,” a strategy used by the group to merge traditional artistic disciplines in ways that challenged the categorical distinctions separating them. For Tone in particular, technology was simply the means through which this interdisciplinary work occurred. Combining electronic music with video and other technical elements, Tone’s works developed parallel to the experiments of other boundary-pushing Kitchen artists, each exploring the philosophical and aesthetic facets of new electronic media as well.

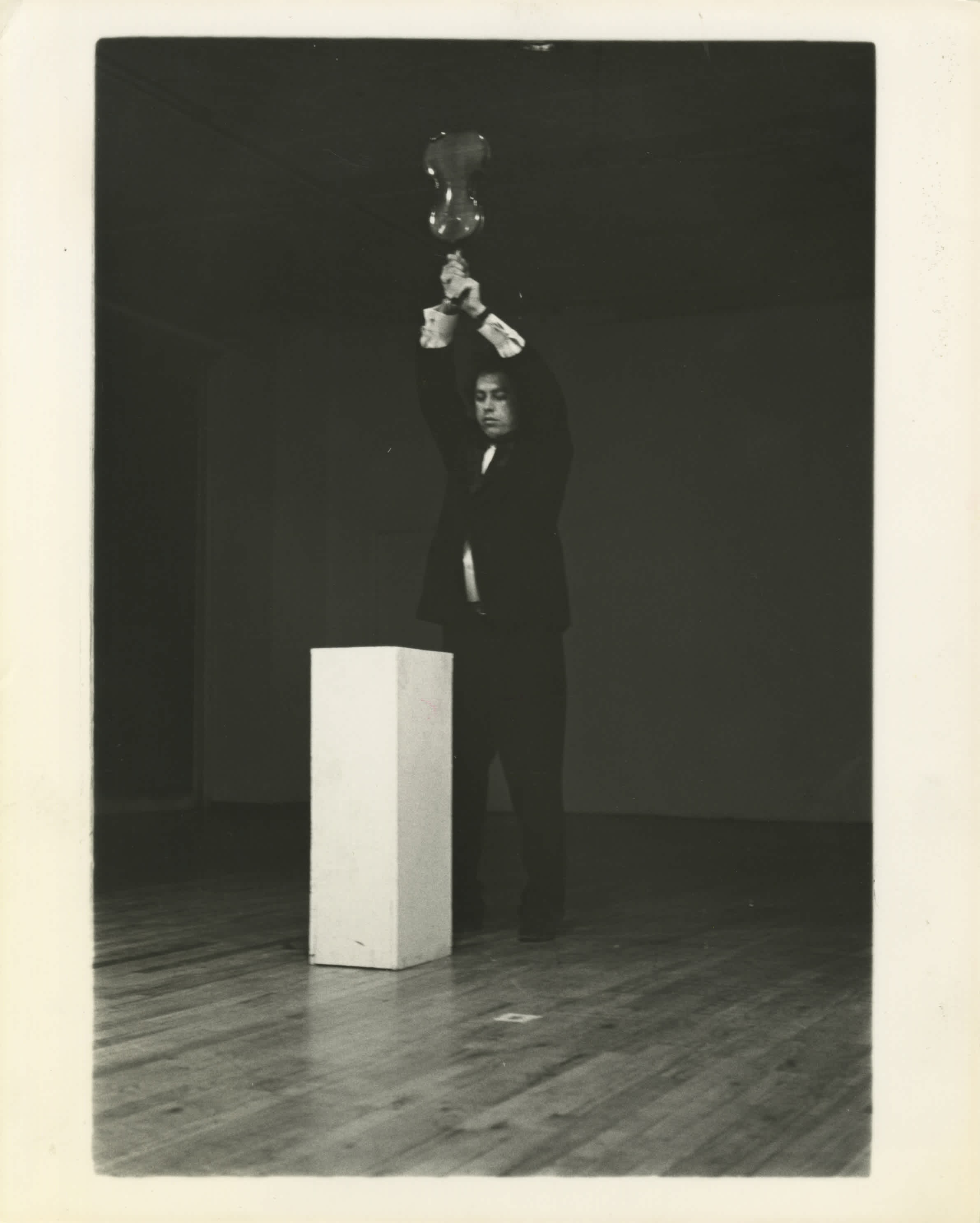

One such artist, who was influential within both The Kitchen and the Video Art Movement more broadly, was Paik. While Paik was not present at the concert itself, Larry Miller helped perform his event One for Violin. Approaching a wooden block that had been placed in the center of the stage, Miller placed the belly of the violin on the block while still gripping the neck in both hands. He then began gradually lifting the instrument, remaining silent for over two-and-a-half minutes as the violin slowly rose above his head. Finally, in a moment of staggering violence, he slammed the violin back down onto the block, where it shattered in pieces onto the stage.

As stated previously, in her scholarship Higgins describes Fluxus’s unconventional interactions with instruments as a way of “knowing” them as objects. Applying this analysis to One for Violin, she observes that Fluxus events can take either a caring, exploratory form or a destructive one: Paik’s work represents one side of the spectrum, whereas Young’s Piano Piece represents the other. This dichotomy demonstrates the intense variability that can occur even among Fluxus events sharing similar formats and performed within one program. There is also a clear relationship between these events and rhythm or time, a characteristic pertinent to Young’s and Tone’s works but most clearly observable in One for Violin’s two-and-a-half minute crescendo. Furthermore, the shock of the piece, generated by the visual element, the sound, and the tactility of the violin shattering, embodies the visceral basis of meaning unique to Fluxus epistemology.

Debuted originally at Neo-Dada in der Musik, a 1962 Fluxus event in Dusseldorf, Germany, One for Violin is a dual testament to the international character of Fluxus and its intertwined history with The Kitchen. This global network was significant to The Kitchen not only because many of the affiliated artists would later perform or show work here, but also because in January of 1984, The Kitchen would temporarily serve as its nucleus. In one of his most important collaborations with The Kitchen, Good Morning Mr. Orwell (and its counterpart 1984 in 1984), Paik would organize and broadcast a live performance of avant-garde artists around the globe to an audience of over twenty-five million viewers. One of the most significant undertakings in the history of video art, the show would involve some of Fluxus’s most important artists, including Charlotte Moorman, Joseph Beuys, Ben Vautier, Paik, and Cage. Although the event took place five years after the already “historical” Flux Concert, these artists, who had all formed relationships and worked together through Fluxus, remained influential and interconnected performers supported by The Kitchen’s institutional platform. The progression from One for Violin (1962) to Good Morning Mr. Orwell (1984) is one of two decades of change in Paik’s own artistic interests, but it also parallels the origins, life, death, and aftermath of the Fluxus movement, as well as The Kitchen’s intermittent role in this course.

The performance described at the beginning of this essay, is Ben Patterson’s Overture (c. 1961), which served as the dramatic conclusion to the night of Fluxus works in 1979. I believe that this group of interconnected performers, each passing something on to the next, could be seen to represent the network of influences and experiments that characterized Fluxus itself: in fact, if these social interactions were the defining facet of Fluxus as a group (as Smith suggests), it was this web of sometimes tenuous connections that characterized the group’s relationship to The Kitchen as well. From the early involvement of Young, Conrad, and Chatham in both Fluxus circles and Kitchen programming to the climactic performances of former Fluxus artists around the world in Good Morning Mr. Orwell, the relationship of Fluxus to The Kitchen was long and deeply complex. Fluxus was established nearly a decade earlier than The Kitchen, yet its artists continued working in New York and at The Kitchen long past the institution’s early years. The boundaries of Fluxus itself were nebulous, from its artists to its timeline to its philosophies, and as artists across disciplines and affiliations rotated in and out of The Kitchen during these same decades, the institution and its network remained similarly in flux. Fluxus and The Kitchen share a lengthy, concrete history—yet fittingly, this history appears as indeterminate as the art of Fluxus itself.