Credits:

By Sofía Benitez, Winter/Spring 2019 Curatorial Intern

May 6, 2019

On April 5 and 6, 2019, Stacy Grossfield presented metamorphosis at The Kitchen as part of Dance and Process. I sat down with Stacy Grossfield, along with performers and collaborators Nola Sporn Smith and Alexandra Albrecht, to learn more about their experiences, process, and work.

Initiated in 1995, Dance and Process is The Kitchen’s longest-running series. For ten weeks, participants discuss their work, develop a performance, and present it to an audience. This year, Dance and Process featured mayfield brooks, Rebecca Serrell Cyr, Stacy Grossfield, and Christopher Unpezverde Núñez and was facilitated by Yve Laris Cohen and Moriah Evans.

What ideas emerged from and informed the making of this work?

Stacy Grossfield [SG]: I thought about kinds of women that feel like characters to me. Sometimes I work from a place of wanting to make characters or people that I can’t relate to at all, I don’t know them. That’s really interesting to me, trying to work on things I don’t know how to make. I started to think of upper-class women, the one percent. They feel like aliens to me. Actually, in the way Nola moves in the solo, she’s an animal. We are all animals; even the uppermost-class women are still animals. Nola’s solo was going between upper-class, one-percent woman, animal, and alien.

Nola Sporn Smith [NSS]: We also talked about scenes in films. Stacy is extremely visual. I remember once in rehearsal for the solo, I ran through it and she asked, “how did that feel?” And I replied, “does it even matter?” She was very respectful of our limits, so it wasn’t a cruel process in that way, but she sat outside of it when she built the piece. It was really from the perspective of the audience, how it would appear and how she could craft the piece to be viewed as best as possible.

What is the relationship between the characters and sections?

SG: I wanted to present this piece in three separate sections: a solo by Nola, a duet, and a solo by Alex. When I think about the idea of metamorphosis, I think about how there is a lot of time between different stages of evolution. Nola’s character is a very early version, a stage with a lot of kinks and issues, things that are not working. What’s inside of her is obviously not herself. Alex’s character is a very highly efficient, pretty finished version of this being but still not quite perfect. Her body is fighting what is inside, the self-trying-to-be. That’s how I really feel about these people I can’t relate to. They’ve really repressed being uncomfortable.

NSS: The sections were sequenced in a very dreamlike way. I often describe Stacy’s work as surrealist dance in the way she distorts a recognizable thing or idea. In this case it was a woman or feminine figure.

Is there humor in the work? Was it intentional, or something you expected?

SG: Part of my work is always humorous, but I never expect it because I learned that you can’t. Nobody laughed as much with my previous work as they did with this piece. In one of the DAP showings, everyone asked me if I was okay with the laughter and I said, “I don’t know how people don’t laugh.” I know for sure because of the way Nola and Alex are working so hard, if a viewer goes into it from a kinesthetic level, especially fellow performers, then they will probably miss the humor because they are seeing it from a different lens. But from a certain view it is really funny—I always laughed in rehearsal.

In the last section I think people only laughed at the special effects. I planted them on purpose because even though it did get very serious, I needed to make sure people knew that the text wasn’t sincere, that it was a parody.

NSS: Both my mother and partner’s mother wondered why people were laughing and felt disturbed by it, thinking the performance was hard to watch. It seemed like we were in pain or doing things that were really difficult. I think they had a personal empathy for women who are in a costume of professionalism [the skirt suits]. Some male-identified people said they couldn’t access the piece fully because it seemed to be about femininity or what women go through. That was interesting to me—I actually felt dehumanized in the piece, so it was surprising to hear their response. I wonder if as performers, Alex and I stay in the realm of being women, or if we ever transcend it—whether it crumbles at any point.

Could you speak to the choices for the visuals in this piece?

SG: I started to think about the characters being like aliens and the idea of a genre—a horror, thriller genre. Something I’ve rarely seen in dance. I’m really inspired by films and wanting those special effects to be onstage with the performers. Dance and Process was an opportunity to go into the far direction I have been wanting to explore, creating real visuals.

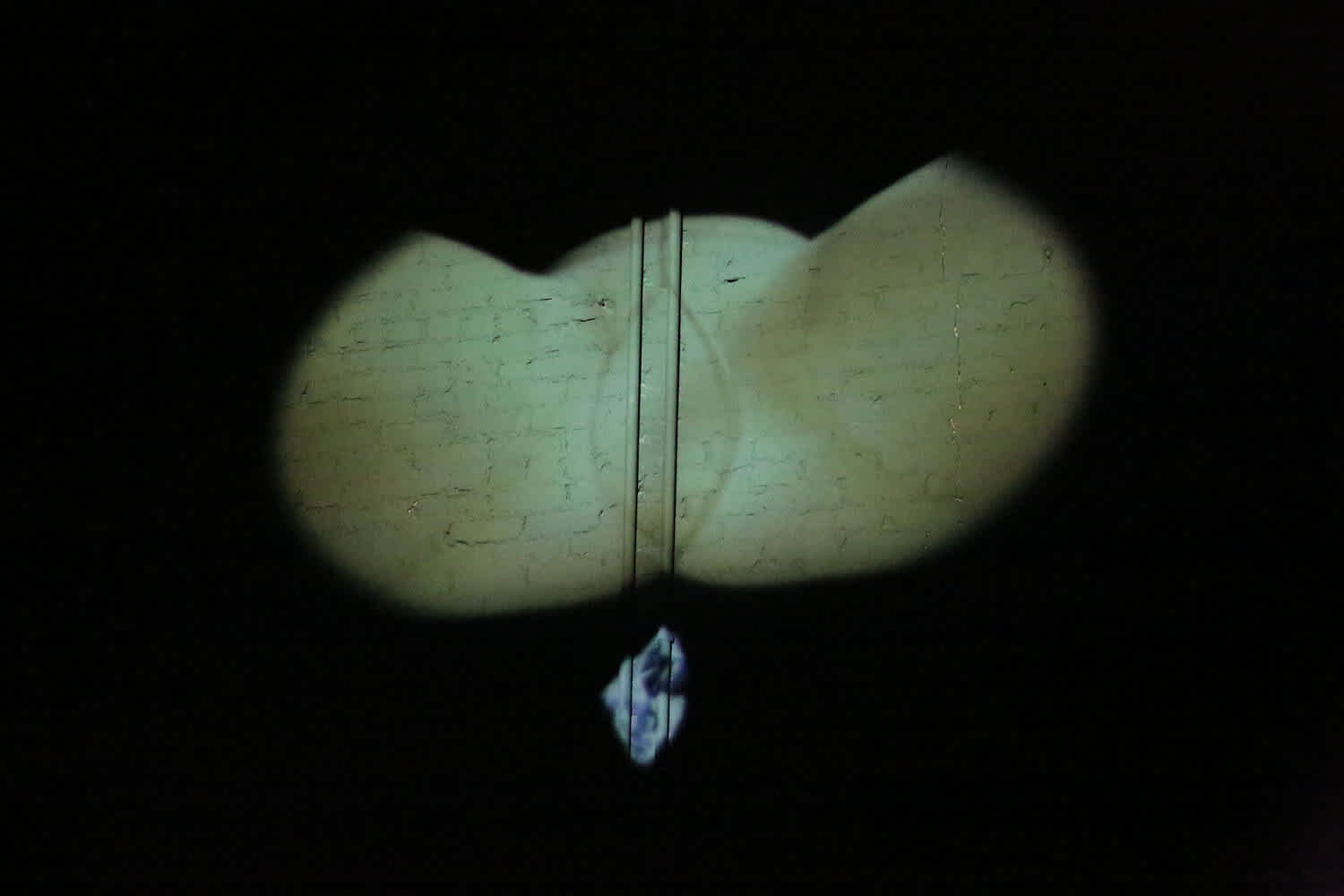

I had a subconscious vision of a crotch with pantyhose. Then one day, it really made sense to me: this character has diamonds coming out of her; she doesn’t actually have genitalia. I’m sure I have a subconscious obsession with Barbie because I played with Barbies like nobody’s business. I was obsessed, and obsessed with them not having genitalia. That fit really well with making the performers not real people.

Alexandra Albrecht [AA]: Stacy also used time as a function to let people hone in on an image and reimagine the possibilities of what is happening. In the duet for example, Nola and I sustained shapes or positions between blackouts.

How do you think about performance and discipline in your practice?

SG: When I create work that is task-oriented, and set up circumstances for performers to navigate, I learned it always achieves rigor in a way that is very real. I set up circumstances such as using costumes and shoes, create shape-based movement, and then try to seal the design of the piece so the “performance air” can’t get in. Negotiating the impossibility of these tasks is what disciplines the work. Sometimes while performing, what happens to your brain and your body feels out of your control, but if you have to really focus in the moment to not let that wig fall off and keep doing those rolls even though there’s paint on the floor and your shoes are slipping, it will achieve this thing where you can’t think about performance.

NSS: Stacy asked me to approach performing this piece as if it were a rehearsal, without the extra energy of performance, or “turning something on” that I have not turned on before. It was challenging to keep my energy dropped and do the task at hand.

AA: I really relate to that. All the work that I choose and chooses me is really dense, physically and intellectually and emotionally. I do get nervous, but once I am in the rhythm of the piece it is very task-based, checking the boxes and getting through the show. When I perform, I can fall into being this character and it’s freeing.

Has this process changed anything about your perception or experience?

AA: I thought about de-sexualizing and de-gendering. How these feminine bodies and feminine outfits could be stripped of femininity into beings, almost like tadpoles. I enter Nola’s and my duet from that place, although a lot of viewers still saw it as Sapphic, which was startling. From inside, it’s not at all sexual to me; it is more about my perception of how my body fits into the work. Our bodies are intertwined in such a way that even in the moments of stillness it is still very confusing. We become one quivering being that is hard to tell apart.

SG: It’s impossible, but I was trying to get people to see these bodies in an abstract way, two-bodies-being-one, seeing them as shapes, deconstructing femininity and womanhood. I realized sexuality is always present when two bodies get close together. I decided I was going to play with that and not ignore it. I wondered if we, as an audience, could go so far in visually that we could sink into new territory. If we watched the moving shape for long enough, could we move past the sexuality? They are two people attached, but I tried to erase any edge of pleasure or caring for each other.

As a performer, with your own investment in your body, was there pleasure in performing this piece?

AA: Definitely. What makes it pleasurable for Nola and me is that we are so connected and so close, and we trust each other so much to get each other through it. Nola and I had not met before although I had been following Stacy’s work forever. There is a cinematic through line in Stacy’s work that makes it stand out from anything else I see. It is something I have always been attracted to and felt to be really powerful.

Could you tell us about working with the structure of Dance and Process?

NSS: It’s exciting to have the continuity of a group watching your work evolve over time, and a diverse panel of people responding to it in a very personal way. Alex and I never saw what anyone else was working on until the dress rehearsal, so it was very intriguing.

SG: Dance and Process raised serious questions about what I am trying to do with my work. Going forward, I feel that the way to approach my work is to have movement push the idea of character, which will inform meaning for viewers.