Credits:

By Sarah Lou Haddad, 2022-2023 Curatorial & Archive Intern

May 30, 2023

“Where performance documentation is concerned, the question of the documentary, or the production of truth and knowledge, arises from a slightly different angle. The intention of creating a link with the live moment is of course inherent in performance documentation. The documents are supposed to provide evidence that the event actually took place.” - Irene Müller (1)

As a time-based medium, performance poses a paradox for documentation. With the advent of video technology, performance has become inextricably linked to video recordings as a primary form of documentation. However, this relationship comes at a price: as with all experiential art, “liveness” is embedded in the meaning of the work, and this liveness is altered with the flattening of video. Performance, in this context, then begs the question: how can we preserve a medium that is antithetical to the objectification of art? Performance at times can rely on memory or objects to carry on its legacy, as it has done since long before video’s existence. Without a camera, preservation becomes about the remnants or traces that are left behind when the performance is over. However, with the accessible and advanced nature of video, is this phenomenon of rejecting our need for video documentation akin to the sentiment of the Luddites? (2)

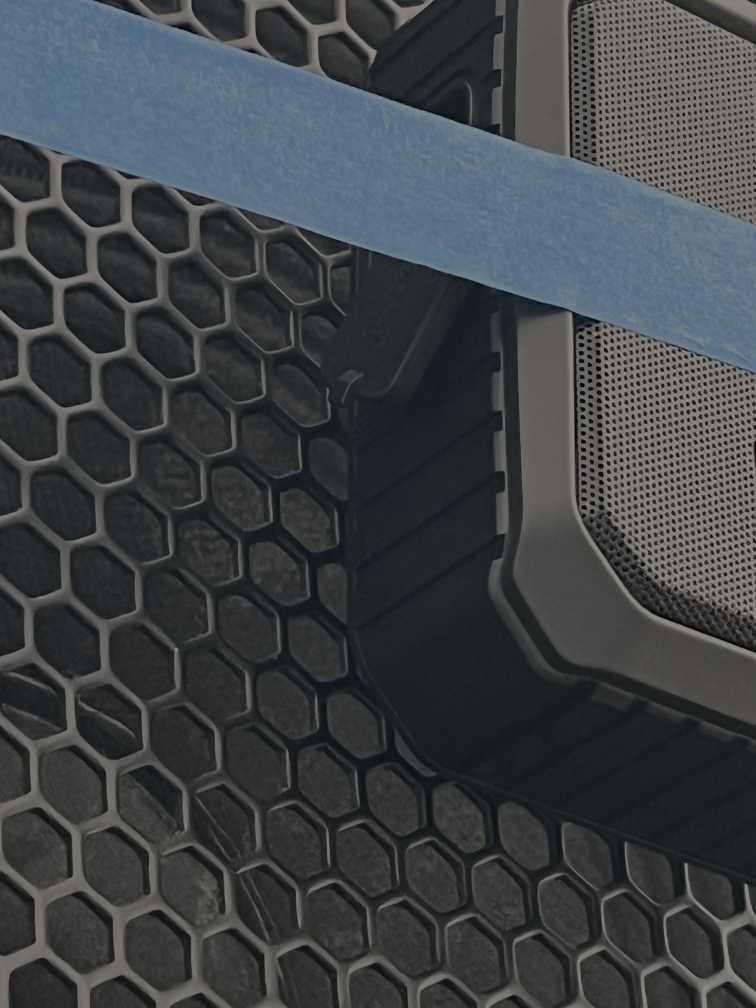

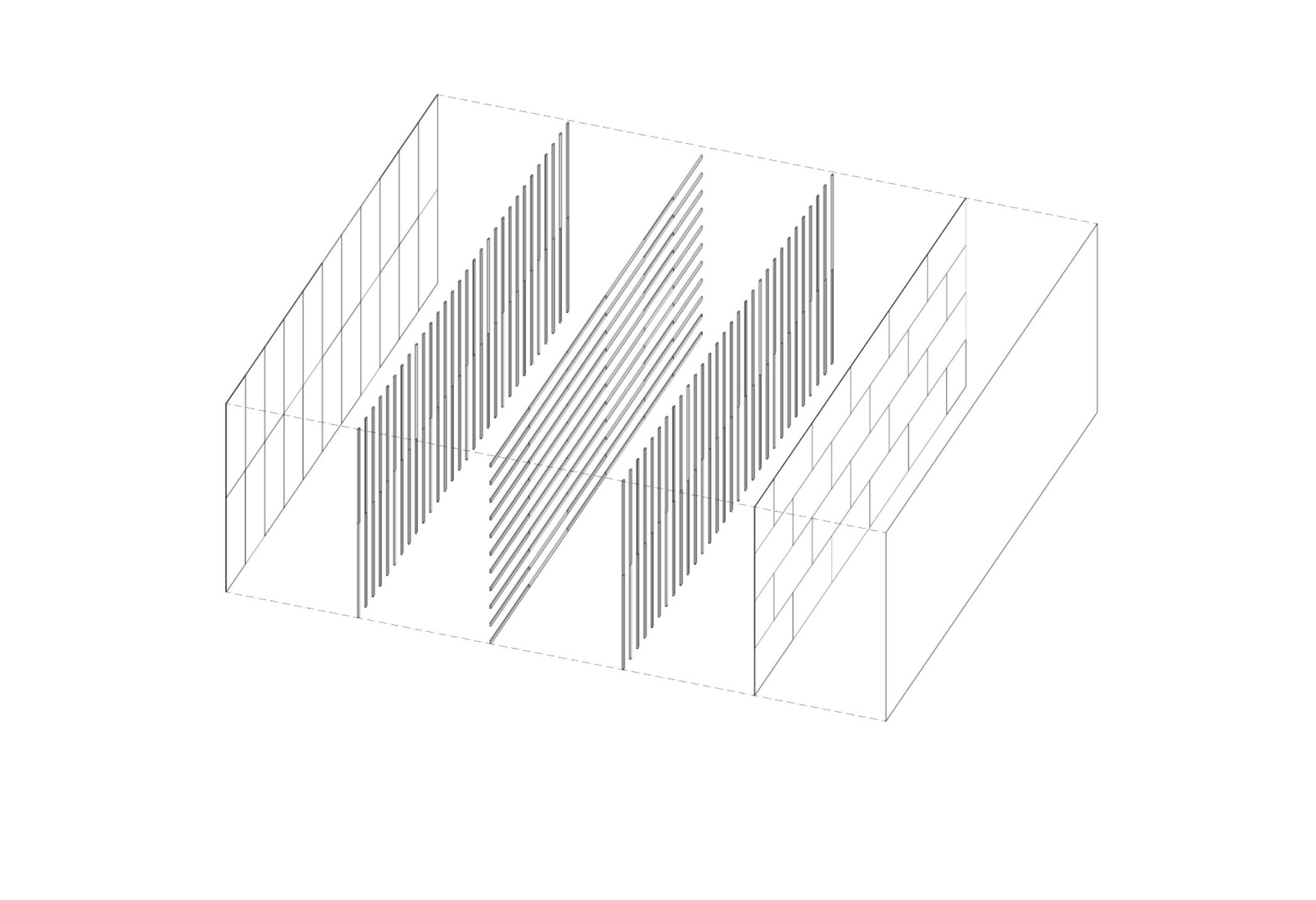

It was a Wednesday in the beginning of November 2022 when I first went to view a performance at The Museum of Modern Art with my colleagues from The Kitchen. I walked into MoMA’s Kravis Studio and took my seat with the other Kitchen folks waiting patiently for Yve Laris Cohen’s Conservation (2022) to begin. Conservation was the second of two alternating performances Laris Cohen staged as part of his exhibition Studio/Theater (2022). With my limited knowledge of Laris Cohen’s body of work, I had no clue what was about to ensue, but my anticipation was building purely in response to the sight in front of me. The other audience members and I were seated at the periphery of the room facing a large, warped grid of rusted metal tubing suspended by wire from the ceiling, hanging precariously just a few inches off the ground. Just to the right of my seat stood two wooden walls wedged between the institution’s structural columns. The windows of this wall were blown out and the wood was singed at the top from what I could only imagine had been a catastrophic event. Later it became clear that the walls and the grid were restored pieces from the historic dance venue Jacob’s Pillow in Becket, Massachusetts—remnants of the Doris Duke Theater, which was destroyed due in the 2020 fire.

The performance started as Laris Cohen walked casually into the room, dressed in the black, utilitarian garb of a stagehand—one of the crew members who the audience typically does not see. Laris Cohen took a knee in front of a contraption that, like the rusted grid hung in the center of the room, was connected with wire to a pulley system on the ceiling. Laris Cohen then attached a handle to the object and started to crank it. The artist continued the cranking motion, which incrementally raised the sculpture higher off the ground, as he called in his first performer, Lynda Zycherman, Conservator of Sculpture at MoMA. He began by asking her a line of questioning pertaining to the condition of the pieces of metal in front of her, and then moved onto queries about what conservation processes MoMA would enact on the metal grid if he were to entrust the piece’s care to them. Zycherman meticulously answered all of the questions Laris Cohen threw at her, even as it became increasingly obvious through her reactions that she was not entirely clued in on what the artist was going to ask. I later found out through Laris Cohen that he improvised all of the questions he asked.The performance continued as Laris Cohen called in his other performers, who included conservation, architecture, and health specialists. One-by-one they approached the grid and answered questions of Laris Cohen’s choosing. The unpredictability of the questions created a sense of suspense for both the audience as well as the performers, waiting as our maestro guided us through the conceptual tapestry he was weaving before our eyes.

The two performances, Conservation and Preservation (both 2022), alternated over the course of twelve weeks, with each being staged six times: each performance included different questions prompting different conversations attached to the same core. While sitting in the audience I started looking around the room feverishly searching for a camera to no avail. The thought that the slight modularities of this iteration of Conservation would be lost, or at least only known to the minds of myself and the other people in the room worried me. Relief came in the form of an older man in the corner of the room seated at a typewriter-like machine who seemed to be transcribing the valuable conversations. In Preservation, it was revealed that his name was Dominick M. Tursi, a stenographer who has worked in court transcription for over fifty years. Tursi was transcribing the performance in stenography, the subjective art of writing in shorthand, and eventually would translate it to English.

After the performance was over, the worry I had felt sent me on a theoretical spiral. I had been pondering the relationship between video and performance in my own art practice, and Laris Cohen had fragmented the fragile understanding I had about that relationship. I had previously thought that due to the prevalence of cameras in the modern age, video documentation was compulsory for all contemporary performances. Although, with Conservation, the transcription and the Jacob’s Pillow artifacts rendered the need for a recording unnecessary. And even if the performance had been recorded, typically institutions only record one of the performances due to the cost of documentation, so this would not capture the variations across the run of performances.

I found that it was equally compelling to think through other performances that happened at The Kitchen through the lens of the decisions made about documentation by artists. I can not help but think about Fine, a performance that Laris Cohen did at The Kitchen in 2015. Fine confronted institutional restrictions and limitations by describing a performance and sculptural piece that the artist proposed that did not happen. The result was a piece that was completely altered from its original conception. In Fine, the artist presented performers with a line of questioning similar to in Conservation/Preservation, revealing that impracticality and monetary reasoning kept Laris Cohen from realizing the piece he’d proposed. When I watched the video documentation in The Kitchen’s archive, I observed that there is an ad hoc quality to it, as it is simply a record of what had happened in the room. This logic tracks back to Conservation/Preservation as Laris Cohen explained to me in an interview I conducted: he mentioned that the dress rehearsal for the MoMA performance was recorded purely for archival and research purposes.

In a 2023 BOMB Magazine interview with Ksenia M. Soboleva, Laris Cohen addressed the subject of documentation by explaining that it is never a major priority for him: “I privilege the live viewing experience for audiences over documentation, and I would rather lack a recording than have obtrusive cameras disrupting the performance environment. I’ve attended many performances where the live audience feels incidental, in deference to future video viewers.” (3) He goes on to explain that in his mind while creating the performances was Juliette Singh’s book No Archive Will Restore You from 2018. In this book, Singh describes the seductive and hopeless desire to be included in the archive of academia. She calls the archive a “pure tease” and says “we were unabashedly shoving borrowed dollar bills down its skimpy thong,” referring to the student debt of her and her fellow graduate students. (4) This book became the explanation of how I was feeling in the audience at Laris Cohen’s performance—Conservation/Preservation was a rebellion against the preconceived normativity of the video archive for performance.

When I spoke with Laris Cohen, I had the desire to understand where the idea to transcribe Conservation/Preservation stemmed from. His answer: Dr. Anne Hutchinson Guest, one of the main innovators of the recording of four-dimensional movement onto paper, better known as music notation. Music notation was Hutchinson Guest’s response to the documentation of choreographed dance performances, as she had disdain for video as a form of documentation for dance performances in particular. Laris Cohen remembers Hutchinson Guest dubbing video “the enemy” when it first became popular as a tool for documentation. (5) In 1953 Hutchinson Guest was asked in an interview about her contempt for video to which she responded: “Can they film dancers from all body angles? And dancers’ clothes get in the way; will they dance naked?” (6) Hutchinson Guest’s sentiments capture the plight of documentation: it can never equal the specificity of the live experience, so it becomes a game of approximation. Laris Cohen revealed to me that he had proposed Hutchinson Guest to be a potential performer in Preservation, but she passed at the age of 103 in April of 2022, before the performances took place. Her potential inclusion as a performer motivated Laris Cohent’s decision to transcribe the performance series. In Conservation/Preservation, Tursi would transcribe not only the conversation between Laris Cohen and the performer, but also the movements unfolding simultaneously along with them. This choreography included Laris Cohen’s cranking movement as well as the non-verbal actions of the performers. Laris Cohen’s cranking movement was documented inherently in physical space by the grid's position, as the cranking slowly lifted the grid up to the top of the room by the end of the performance. The grid's capacity for movement insights a potential energy that can be released only by the artist. Whether at the top of The Marie-Josée and Henry Kravis Studio or the bottom, the grid's position is a signifier of the action that occurred, prompting unique interactions if encountered outside of the performance duration. Between the physical artifacts of the grid, the theater wall, and the Stenographic transcriptions, a record of the specificity of the experience exists here without a camera. Laris Cohen reflected on the pitfalls of documentation and compensated tenfold, sacrificing the camera for the sake of uniqueness recorded within twelve individual transcripts, one for each evening. I was struck by the revelation that Laris Cohen created a performance piece that was self-preserving and independent of videographic documentation.

Furthermore, it felt to me that Laris Cohen was fighting for the permanence of the Jacob’s Pillow artifacts within his line of questioning. A prominent theme in Laris Cohen’s work is the idea of care, and this performance was no different: he asked the audience and the performers to take a deep look at how institutions enact care—hence the ideas of “conversation” and “preservation.” The idea of care extended further when Laris Cohen interviewed his last performer, Lisa B. Malter: the artist’s personal gastroenterologist. Laris Cohen asked Malter to elaborate on the status of his chronic disease in relation to his body as a trans person. The pipes in front of me suddenly turned to intestines in my mind's eye. Serpentine and rusted, held together miraculously by shiny silver screws that became a metaphor for the temporary medical solutions intended to mitigate the effects of chronic illness. By the end, the earlier conversations with Zycherman and other conservation specialists felt a lot different. Laris Cohen was bargaining for the conservation of the pieces in front of us as an extension of his own interior.

In Soboleva’s interview with Laris Cohen, she asks the artist about his relationship to documentation as it relates to the elusive nature of queer histories as well as performance. Laris Cohen responds, “My allergy to video documentation does come from a queer place, I think; although archival practices can of course themselves be queer, as can the material attachment to, and the desire for, the archive’s holdings.” In my own conversation with Laris Cohen I asked him to elaborate on this, as it felt significant to acknowledge in relation to the documenting of Conservation/Preservation. Laris Cohen explained how queer bodies had been ignored from the pages of history for so long, yet visibility and representation comes at a price. To be documented is to be seen, which can become a sort of trap, placing a target onto vulnerable populations. There is also an element of dysphoria that comes along with one's image, as the archive can preserve past versions of one’s body. As Laris Cohen described it, this dissociation with documented past bodies can be a difficult thing to confront. The refusal of the camera in the case of Conservation/Preservation becomes a source of protection, offering an alternative to the dysphoric experience of peering into a misaligned reflection.

CREDITS & FOOTNOTES

(1) Irene Müller. “Performance Art, Its ‘Documentation,’ Its Archives.” Performing Documentation in the Conservation of Contemporary Art, Instituto De História Da Arte, Lisbon, 2013, p. 21. (2) One of a group of early 19th century English workmen destroying laborsaving machinery as a protest or more broadly: one who is opposed to especially technological change. Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary, s.v. “Luddite,” accessed April 20, 2023, https://www.merriam webster.com/dictionary/Luddite. (3) Ksenia M. Soboleva and Yve Laris Cohen. “Performance as Archive: Yve Laris Cohen Interviewed.” BOMB Magazine, December 13, 2022. (4) Singh, Julietta. “No Archive Will Restore You.” Essay. In No Archive Will Restore You, 22. punctum books, 2018. (5) Martha Joseph and Yve Laris Cohen. “Chronic Theater: An Interview with Yve Laris Cohen: Magazine: Moma.” The Museum of Modern Art, November 7, 2022. https://www.moma.org/magazine/articles/814. (6) Neil Genzlinger. “Ann Hutchinson Guest, Who Fixed Dance on Paper, Dies at 103.” The New York Times. The New York Times, April 15, 2022. https://www.nytimes.com/2022/04/15/arts/dance/ann-hutchinson-guest-dead.html.