Credits:

By manuel arturo abreu, non-disciplinary artist

October 16, 2023

To experience Love — To give Love — To receive Love —

To share Love

In Life — To make it Work through Work

To search for a Way to see if Life and Living in itself is

Art by being a Creative process

– Moki Cherry, July 2, 1973 (1)

Don and Moki Cherry’s Organic Music Society was a family’s effort to build a nourishing context for aesthetic production and contemplation. For a decade, orbiting a schoolhouse in Tågarp, Sweden, the American trumpet player (Don) and Swedish visual artist and designer (Moki), as well as their children Neneh and Eagle-Eye, explored the worldmaking capacity of communal sounding, improvisation, and spiritual nomadism with this Gesamtkunstwerk. Ensconced by Moki’s textiles, their band performed simple, spiritual melodies with casual rigor, drawing from the pair’s global travels in the sixties. Their creative output also incorporated activities such as cooking and eating food, organizing workshops, and hosting a wide range of performers, collaborators, and students.

I learned of this project at the same time as The Kitchen invited me to write a new text that engaged their archives. I discovered that the institution hosted an Organic Music Theatre concert series in 1976, during which Don and Moki performed, as a New York Times review reported, a type of music that aspired to be “universally accessible.” (2) I sought to conduct an ethnography of this performance, but in conversation with Rhys Chatham learned that the recordings of the event were stolen (3), and scant record seems to exist in the public memory aside from some short reviews.(4) To honor this lacuna around this particular concert, I turn to the Organic Music Society project as a whole, considering its continuing relevance, and in particular the importance of Moki Cherry’s visionary contribution.

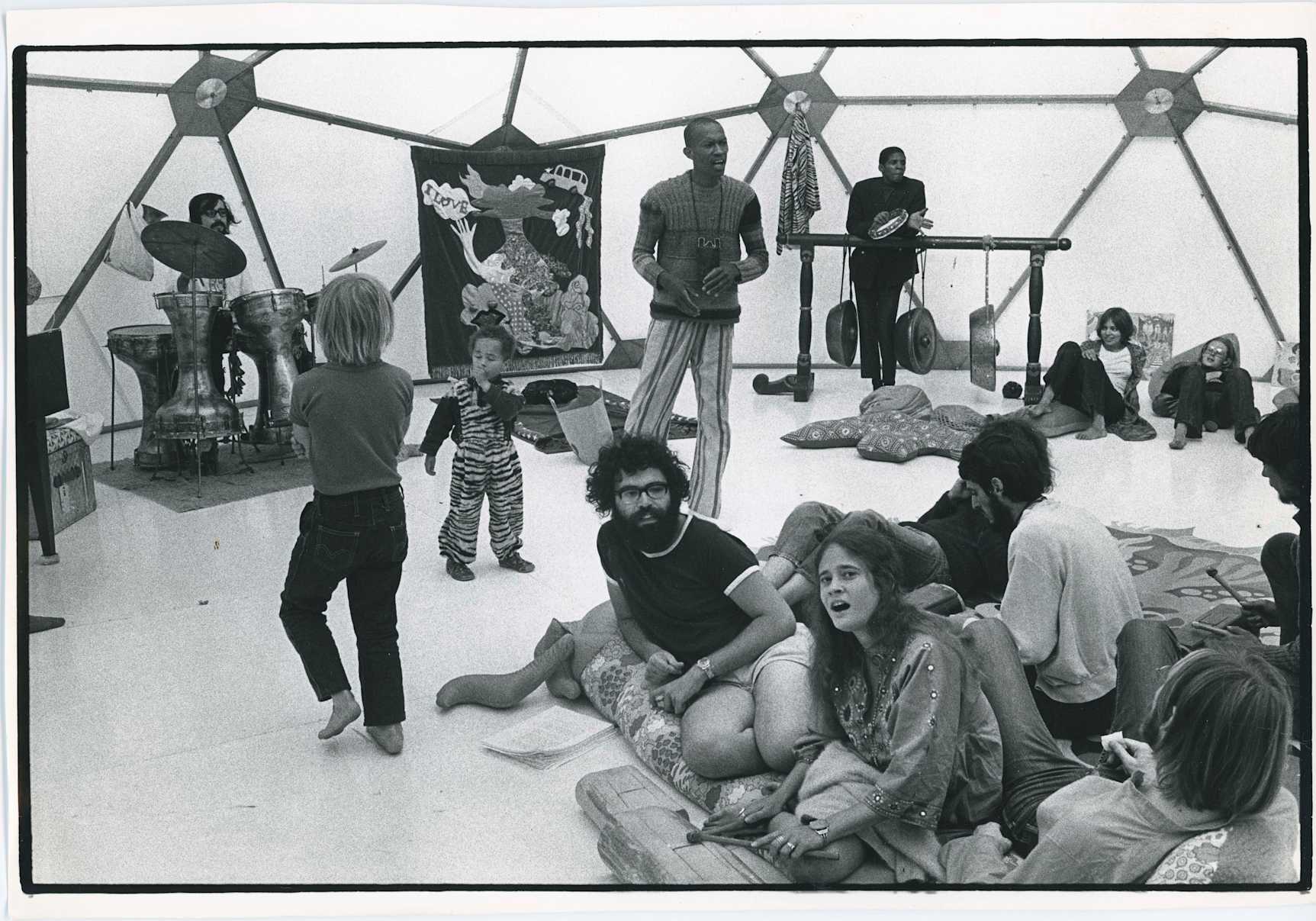

Don and Moki met in Sweden in the early sixties, during the period when he performed, taught, and apprenticed with musicians across the world. In that era, Moki had a practice of opening her home to jazz musicians touring in Scandinavia. One of these musicians, George Russell, introduced her to Don. (5) Thereafter, the two sought to build a life together, marrying in 1963 and going on to live in various places in Europe, Africa, New York City, and Congers, NY.(6) Don was becoming increasingly dissatisfied with the commodification of American jazz: it had lost its connection to its communal, spiritual roots. In a radio interview, Don tells the interviewer: “We [Organic Music Society] started out as Movement Incorporated. This is the period of my life when I decided I didn’t want to play nightclubs, [I’d] rather play under the environment which I felt was in tune with the type of music I was connected with.”(7) He and Moki were interested in co-living, organic farming, and spiritual exploration, which led them to move to the rural area of Congers, NY around 1969. Here, they lived in a geodesic dome and built a self-sufficient community that included other musicians, artists, and like-minded individuals. Cherry's departure from the New York City jazz scene to create a new setting in Congers thus reflected his desire to break traditional musical and societal norms and explore new possibilities for creative expression through community. Moki was the perfect collaborator for this vision.

In Congers, racist realtors refused to sell the couple a house; this, paired with anti-miscegenation sentiment from townspeople, prompted them to leave Congers and formalize their collaboration elsewhere. Choosing to ground themselves in free collective living, listening, and sounding, Don and Moki moved to Tågarp where they co-lived and co-worked throughout the seventies with their kids in an abandoned schoolhouse they purchased for $4,000.(8) Not coincidentally, this remote, southern Swedish town was also far away from New York City’s heroin-laced downtown club scene. Here, in the merging of domestic and performance space where, as Moki said, “the stage is home and home is a stage,” Don pulled from threads that he identified as “organic” during his global travels to catalyze a collaborative, life-affirming project in tandem with Moki’s design and home-building practice.(9) The Organic Music Society and Organic Music Theatre expanded the liberating resonance of free jazz to include life itself, freely inviting others to join in their project of “improvising on stage and in living,” as Moki wrote. To live in this way is to lean into the nourishing potential of attending to the fleeting moment.

The pair began touring the Organic Music Society even before Tågarp. In one of the project’s earliest travels, for almost three months, they replicated the Congers geodesic dome for the 1971 exhibition Utopias and Visions 1871–1971 at the Moderna Museet in Stockholm. Other artists in the show, local and traveling audience members, and staff all passed through the space the Cherrys built, leaving their mark via their presence or through specific interventions responding to the context. Another example of early work: the first audiovisual and theatrical performance that Don and Moki led under the name Organic Music Theatre was at the 1972 Festival de jazz de Chateauvallon in the South of France, which is captured on the LP Organic Music Theatre (Blank Forms Editions, 2021). The group traveled to the venue in a van, gathering puppeteers, dancers, and acrobats along the way. On the outdoor amphitheater stage, a dozen Danish adults and children contributed with sound and movement to the performance. Later that year, they recorded Organic Music Society (Caprice Records, 1972), a masterpiece that explored the common language Don had crafted between disparate global genres, de-centering his own authorship and mastery in favor of performing compositions by other composers in a group setting.(10) “It is not my music,” Don once said of his work.(11) He and Moki sought a universal, free sound owned by none but accessible to all– music as a facet of the organic environment. As Don put it: “I wanted to play different instruments in… natural settings like a catacomb or on a mountaintop or by the side of a lake. I wasn’t playing for jazz audiences then, you realize. I was playing for goat herders who would take out their flutes and join me and for anyone else who wanted to listen or to sing and play along. It was the whole idea of organic music—music as a natural part of your day.”(12)

As such, even while the Organic Music Society would come to be anchored in the schoolhouse, the project environment was mobile, spatially choreographed by Moki’s resoundingly colorful sacred tapestries, stage sets, and costumes: “Wherever we were was home, so we started working together—and living it,” Moki wrote in her diaries. Operating simultaneously as art and portable functional object, Moki’s textiles sculpted the timbre of the space of performance by damping and emphasizing certain frequencies and spatially generating the contemplative, improvisatory context of the “organic.” Her drawings and tapestries took on additional roles by serving as the visual component of concert posters and LP covers throughout the seventies. One of Moki’s most beautiful tapestries, from 1976, reads “Organic Music.”(13) Another features the syllables of Indian classical music, to be activated by performers and audiences in contexts where it hung.(14) Indeed, Ben Young states: “Moki’s tapestry was the symbol, score, and at times lyric sheet for the music.”(15) Further, the content of the textiles elucidates the nature of the project: when I try to define “organic music” for myself, particularly its spiritual or contemplative components, I think of two other textile works by Moki. One reads “ORGANIC THEATRE OR THE LIVING TEMPLE.” The other: “music of universal silence.” Here I imagine a sound so big and loud it can’t be heard. A silent sound of such scope demands a specific ethics of living grounded in vigilance toward the invisible and unheard, something like faith.

There is a precedent for Moki’s use of textiles in Organic Music Society environments: while spending much time on the road touring in the late sixties and early seventies, Moki, Don, and their children also lived in a rented apartment in Gamla Stan, Stockholm, whose walls and ceiling Moki had elaborately decorated in order to transform the function and spatial choreography of rooms. For example, Moki turned certain spaces into playrooms for the children. A Swedish newspaper photographed the apartment and quoted the couple speaking about the importance of a portable domestic space given Don’s touring schedule. Moki’s colorful tapestries, fabrics, and costume designs established a necessary flexibility that seamlessly fit their private domestic lives, their later semi-public project at the Tågarp schoolhouse, and their public-facing projects at venues and other institutions. The ability to build a mobile home is more than anything a practice of relation, of building a common language among disparate perspectives. Such relationality links Don’s global music studies with Moki’s mobile design language.

Just as her tambura playing for the musical performances served as more than a droning background, Moki's tapestries were more than just decorative backdrops: they were an integral part of both setting the stage and of the action, as performers activated and were activated by them. During performances, Moki would often wear and hold textiles she had designed and created, such as brightly colored robes and headpieces. She also designed a number of costumes for Don. In other cases, Don would interact with her pieces by playing his trumpet while standing inside a large tapestry, creating a sonic and visual effect that blurred the boundaries between the musician and the environment and reimagined the performance environment as a built domestic space (and vice versa). Along with his trumpet mute, playing from within the tapestries allowed Don to shape the timbre of his pocket trumpet. Moki's textiles also played a role in the audience’s participation. For example, during a performance of the composition "Eternal Rhythm" in Copenhagen in 1968, the audience was encouraged to move around the space and interact with the performers and the textiles.

Moki saw her tapestries as an extension of her domestic life, and she often drew inspiration from her experiences of creating a warm and welcoming home environment. For Moki, the stage was not simply a performance space; it was a home, a place where the performers and the audience could come together and share in a communal experience they conjured together in the moment. By creating tapestries that evoked a sense of both domesticity and sacredness, Moki sought to blur boundaries between the stage and the audience, and to build a sense of intimacy and connection between the performers and the viewers, emphasizing the equality of all involved. Moki's notion that "the stage is the home and the home is the stage" reflected her desire to make a more inclusive and participatory form of artistic expression, one that invited the audience to become active participants in the performance. By inviting the audience to touch and interact with her tapestries alongside the “real” performers, Moki created a sense of community between performers and viewers.

The extensive labor of care that drove Moki’s contribution to organic music is more relevant than ever today, in a time of information overload, structural isolation, and violent global extraction.(16) Moki’s concept of cooperation and shared understanding through art and design ties directly into the idea of organic music, which centers the importance of collaboration and the breaking down of barriers between different cultures and musical traditions. Lofty as it may seem, the Cherrys saw organic music as a way of creating a more harmonious and interconnected world: the genre described not simply a style of playing, but also a philosophy that emphasizes the importance of collaboration, improvisation, and open communication. In this sense, we can see Moki’s tapestries as an embodiment of the principles of organic music, as they invite participation and collaboration and help to create a sense of shared experience and community among the performers and the audience. Further, in journal entries, poems, and drawings with linguistic content, Moki described improvisation as central to being. For me, this evokes notions of eternal performance and ties into Moki’s early practice of hosting jazz musicians. From the journal entries and art documented in the publication Organic Music Societies, it’s clear to me that this notion of process with no end or beginning was something like the divine for Moki. The timeless, sacred duty of sharing space together locates sound as a host consciousness in the rehearsal of community. Making space for oneself and for others is a kind of sounding.

BIO

manuel arturo abreu (born 1991, Santo Domingo) is a non-disciplinary artist who grew up in the Bronx and lives and works on unceded lands of First Peoples of the Pacific Northwest. abreu works with what is at hand in a process of magical thinking with attention to ritual aspects of aesthetics. Since 2015, with Victoria Anne Reis, they have co-facilitated home school, a free pop-up art school with a multimedia genre-nonconforming edutainment curriculum, including residencies at Yale Union (2019) and Oregon Contemporary (2022–23). They’ve exhibited at Kraupa-Tuskany Zeidler (Berlin), Simian (Copenhagen), Kunstverein München (Munich), the Portland Art Museum, Palazzo San Giuseppe (Polignano a Mare), Halle Für Kunst Steiermark (Graz), Kunstraum Niederösterreich (Vienna), the Studio Museum in Harlem, Veronica (Seattle), and the Athens Biennial 7. They’ve published with Art in America, CURA, the Serpentine Gallery for their Hervé Télémaque catalog, the Institute for Studies on Latin American Art, X-TRA, and Rhizome.

Footnotes

(1) Moki Cherry, July 1973 diary entry from “Life Writings, Diaries, and Drawings,” in Organic Music Societies, eds. Lawrence Kumpf, Naima Karlsson, Magnus Nygren, (New York: Blank Forms, 2021), 306.

(2) Robert Palmer, “Don Cherry, Jazz Trumpeter, Plays and Sings at the Kitchen,” The New York Times, Oct 26, 1976.

(3) Rhys Chatham, Zoom conversation with the author, October 2021. At the time of the Organic Music Theatre concert, Chatham directed the music program at The Kitchen.

(4) I also emailed a number of audience members; few had any particular memories. One person who would prefer anonymity wrote back, for example: “Hah, an ancient history query! Unfortunately, my recollections of the event are more than a bit hazy. I remember the scene, with Moki's tapestries hung behind the musicians and, I think, their kids running around. Moki was on tambura pretty much and, truth to tell, I found her presence a bit off-putting, kind of aggressively spiritual, if you will.” French composer Ariel Kalma wrote back: “... I don't remember much of this, a long time ago... But I was impressed by the cohesive happening between those musicians…”

(5) The story of how Moki met Don Cherry through George Russell is mentioned in Moki Cherry's journal entry dated February 10, 1963. This entry and all diary entries I quote in this essay are from Organic Music Societies, eds. Kumpf, Karlsson, Nygre.

(6) Some places Don Cherry visited, many with Moki, include: in Europe—France, Spain, Italy, Sweden, Denmark, the Netherlands, Germany, Switzerland, Austria, and Norway; in Africa—Morocco, Mali, Senegal, Ivory Coast, Ghana, and Nigeria; in the Middle East and Asia—Turkey, India, Nepal, and Japan; in South America—Brazil, Argentina, and Chile. See Moki’s journal entries in Organic Music Societies, Kumpf, Karlsson, Nygre, eds.

(7) This radio interview between Don Cherry and Christopher Brewster first aired on March 12, 1970, on WDCR, Dartmouth’s free-form community radio station, during Cherry’s tenure as an artist-in-residence at the school. Christopher R. Brewster and Don Cherry, “An Interview with Don Cherry,” in Organic Music Societies, eds. Kumpf, Karlsson, Nygre, 251–252.

(8) Today, this would be equivalent to a bit more than $30,000.

(9) Moki Cherry, “Life Writings, Diaries, and Drawings,” in Organic Music Societies, eds. Kumpf, Karlsson, Nygre, 282.

(10) Such compositions include pieces by Terry Riley, Pharoah Sanders, Abdullah Ibrahim, and others, and Naná Vasconcelos’ interpretation of a north Brazilian ceremonial hymn.

(11) Cherry quoted in Magnu Nygren, LP liner notes for Don Cherry's New Researches featuring Naná Vasconcelos, Organic Music Theatre: Festival de jazz de Chateauvallon 1972 (Blank Forms Editions, 2021).

(12) Don Cherry, quoted in Francis Davis, “Don Cherry: A Jazz Gypsy Comes Home,” Musician, March 1983, 54.

(13) The text “Organic Music” is stitched in white in an arc on a split plane whose top half has a gorgeous golden-yellow pattern of birds and leaves, while the bottom half is creamy white with a geometric pattern of red and blue triangles and blue dots. Over this is a winged heart symbol with an ear (with a star in the lobe) in its center. From the vertex of the heart and its outstretched wings rise two green forearms whose hands are touching at their fingertips—the left one with a sun in its palm, the right one with a crescent moon—as well as a heart and a pair of wings.

(14) For example Sa, re, ga, ma, pa, da, etc.

(15) Ben Young, “Relativity Suites,” in Organic Music Societies, eds. Kumpf, Karlsson, Nygre, 393-414.

(16) Forbes reports that 73% of surveyed Gen Z youth report feeling lonely most of the time. See: Kian Bakhtiari, “Gen-Z, The Loneliness Epidemic And The Unifying Power Of Brands,” Forbes, July 28, 2023, https://www.forbes.com/sites/kianbakhtiari/2023/07/28/gen-z-the-loneliness-epidemic-and-the-unifying-power-of-brands. Vox reports that 22% of surveyed millennials have zero friends. See: Brian Resnick, “22 percent of millennials say they have ‘no friends,’” Vox, August 1, 2019, https://www.vox.com/science-and-health/2019/8/1/20750047/millennials-poll-loneliness.