Credits:

By Beau Bree Rhee, Artist; Alison Burstein, Curator; Angelique Roasales Salgado, Curatorial Assistant; Legacy Russell, Executive Director and Chief Curator

February 19, 2025

In 2022, The Kitchen partnered with Madison Square Park Conservancy to present the performance Shadow of the Sea by Beau Bree Rhee on three occasions between September and October. This new performance, conceived in dialogue with Cristina Iglesias’s exhibition Landscape and Memory at Madison Square Park (June–December 2022), brought live performance outside the walls of The Kitchen and into the public spaces of the park and city streets. Shadow of the Sea took shape as what Rhee called a “dance poem” composed of eight unique stanzas. Following an initial stanza in the form of a migratory score that began simultaneously on the east and west coasts of Manhattan, the remaining seven sections of the piece unfolded on the Oval Lawn in Madison Square Park, where Iglesias’s exhibition was installed. Video documentation of the piece is available to view in the On Screen section of the website.

One year after the performance took place, Rhee joined members of The Kitchen’s curatorial team—Alison Burstein, Angelique Rosales Salgado, and Legacy Russell—to reflect on Shadow of the Sea’s relationship to the artist’s practice, the work’s unique characteristics as a performance for public space, and the references and collaborations that informed the piece. A transcription of this original conversation was published in an artist's publication for a workshop titled "CHOREO-GLYPHS" at Yale School of Art in fall 2023. Revisiting the conversation for the context of On Mind, an abridged version of the dialogue appears below, accompanied by documentation of the performances in 2022.

Alison Burstein (AB) To begin, we’d like to talk about the emergence of the piece. Shadow of the Sea was born out of an invitation to create a new work in dialogue with Cristina Iglesias’s exhibition Landscape and Memory at Madison Square Park. Iglesias’s exhibition comprised five bronze sculptural pools installed along the path of a creek that used to run through the site, reflecting on layers of buried histories. I was interested in creating a point of contact between your work and Iglesias’s exhibition based on what I recognized as a number of resonances with the themes you explore across your practice—including the connections between the deep past and present, the palimpsestic qualities of landscape, the potential of mapping as medium. Could you begin by speaking about some of your earlier projects, and reflect on the ways Shadow of the Sea built on the ideas or working methods you had been exploring previously?

Beau Bree Rhee (BBR) The context for Shadow of the Sea stems from my work during the pandemic. This was centered around the new earthwork Dream Garden in the Anthropocene (2021– ) in East Hampton, which is a project on a 30 x 300 foot land lot I purchased in a “ghost forest” on Long Island (a forest where a significant number of trees have died due to climate change and invasive species), where my collaborators and I have planted a regenerative cover crop garden and created performance-offerings to the land and its inhabitants. During my residency at Ma’s House & BIPOC Art Studio, I created new paintings and performance work, and developed meaningful relationships of Indigenous allyship with Jeremy Dennis, who runs Ma’s House, and with the Shinnecock Kelp Farmers Coop. Some of my key research references include books by ecofeminists like Vandana Shiva’s Soil not Oil (2007) and Leah Penniman’s Farming While Black (2018) and the essay “A Garden that is a Sculpture” by Isamu Noguchi (1965).

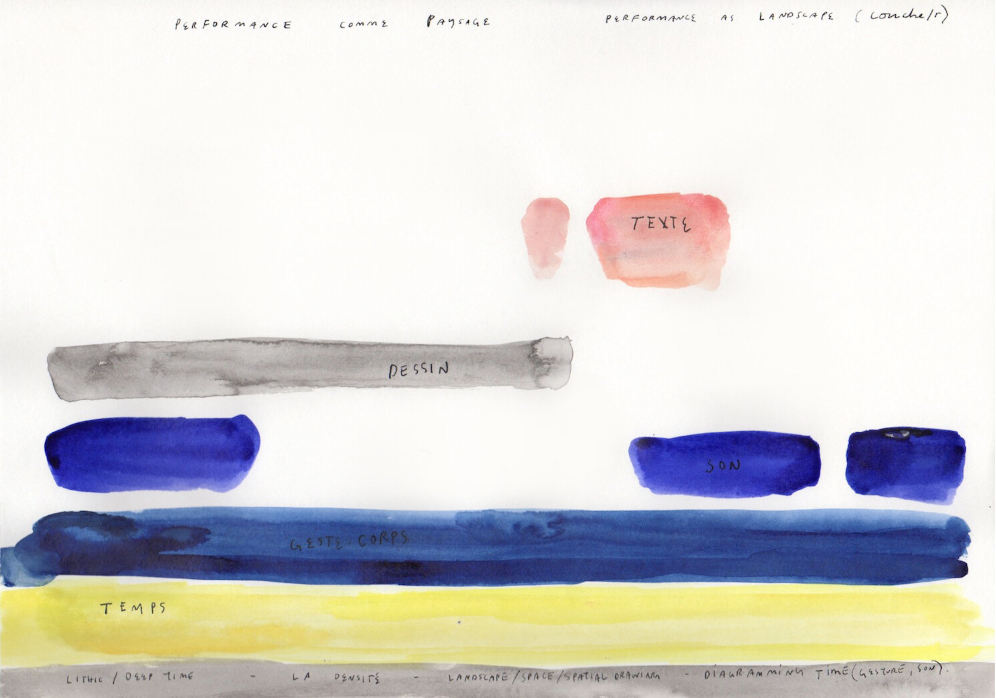

Another relevant work is Performance Paysage (2020), which is a performance that premiered on March 13, 2020 at Daniels Gallery, University of Toronto. I later worked with you, Alison, to present an edited recording of that piece for an installment of The Kitchen’s Video Viewing Room series in September 2020. Performance Paysage is a score with poems, and some song, revolving around the idea of performance as landscape. In this work, I began to probe the body’s endlessly porous relationship to atmosphere through the section of the piece titled “Chorus of Breath.” The tone of the work is dark, rageful in some ways, dealing with grief in the age of the Anthropocene. In Shadow of the Sea, the tone is less dark, but I built on some of these ideas of body and landscape, extended the use of scoring and poems, and drew some visual crossovers in the movements.

I also built on the dance film that Jeremy Dennis and I created together, Les Parages East West (2021), which is based on the Indigenous spiritual belief that souls enter the body from the East and leave to the West. This is a piece where the body is acting as a sort of cosmic lattice, where the Indigenous religious beliefs and spiritual myths are highlighted or mapped or formalized geometrically through the body. Then the body is also a lattice for the actual landscape in some way, as the sun and atmosphere shifts, too. I quote Les Parages East West directly in one section of Shadow of the Sea.

This situation of my practice met this incredible proposition to create a work in dialogue with Cristina Iglesias’s installation. There were a couple of things I noted about her work. I made a note during one of our first meetings with her about the idea that ecology is boundless. Because Iglesias’s piece was referencing historic ecology, I wanted to extend the hinge from past time to future time, with Shadow of the Sea reflecting forward. I additionally was really inspired by the modesty of Iglesias’s intervention in the park, which took the form of buried bronze sculptures tracing the path of the historic stream. There was a subtlety there, and a kind of anti-ego stance. The grandeur of the bronze material was so intense, but then she made a point to hide it away in the grasses that she planted along the edges of the sculptures.

Everything I just described sort of washed through my body, and the movement language that emerged for Shadow of the Sea was new, unexpected, and different.

Legacy Russell (LR) I’d like to talk about the question of the site, noting that this was the first time you had performed in public since the pandemic. The performance centered on Madison Square Park, but it took on a format that began by stretching across two parts of the city. The first section of the work was a migratory score on the east and west coasts of Manhattan—titled A Brutal Meditation (A brisk walk with tenderness at the corners)—that traced where the sea may eventually reclaim the land within the next hundred years. The remaining sections of the piece took place on the Oval Lawn in Madison Square Park. This format allowed for a more expanded view of histories and associations in relationship to New York City as an additional protagonist or performer within the work and also as a collaborator.

The way the performers traveled different parts of the city to meet in a center point brings up this question of public in a different way—recognizing that there were strands of the performance that really bloomed and were contingent on an engagement of the public that occurred unexpectedly across the performances. This, of course, becomes its own score. I’m curious to hear you reflect on that too.

BBR New York City is the ultimate collaborator and the ultimate performance piece. Madison Square Park is also smack dab in the middle of this pulsating, extravagant, glamorous neighborhood. I think as a site, it was quite overwhelming at first. Because as a performer, you want to be adding something. And what can you add to the incredible life pulse of NYC?

I think one word that gave me some liberty was this idea of the Commons. At that time in 2021, we were still masking in public, we were still masking in rehearsal, we were very much coming out of this specific moment of the pandemic.

And here we were, kind of revisiting the Commons. So, some of my background research was looking at the texts of landscape architects like Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux— who shaped our city with Central Park, Prospect Park, and others—and Roberto Burle Marx. They all thought about what the role of a park is in the city. A park is a pretty modern thing, because parks only really exist in cities: if you’re outside the city, you have nature.

I began to rethink Olmstead and Vaux’s concept for Central Park. The park’s history is very problematic, and its construction displaced a lot of communities. But the narrative around it was that it was supposed to be a place of common dignity for all New Yorkers. Olmsted and Vaux imagined the park as a “walking gallery of pictures for the public.” And this quote kind of got me somewhere.

I also had in mind an idea that I’ve kind of latched onto since around 2005, which is a fascination with the etymology of the word choreography. Choreo – the body; graphy –writing. Writing the body.

So, if the landscape architect is creating a walking gallery of pictures, what might happen if that is flipped somehow through the writing of the body?

I asked myself: what do you give the Commons? You give the Commons something like a glyph, something like a poem, something almost classical in nature, like imagining something a bard might read at 6 pm as people are going home. This is how I came to the idea of the dance poem, which is the term that I use to describe my piece.

Legibility was another thing that I was thinking about a lot. How do you create something that won’t just be like a bunch of smoke in the air in this site; something that will be legible to the Commons, to folks who are just passing by, who might just be stepping in for a couple of minutes?

Once I had the idea to create hieroglyphic choreography—images that were bold and legible from many different angles, in a prismatic way on that lawn—then the ideas started coming very quickly. The opening section, the walks along the east and west coasts, felt like the most urgent aspect of the piece. For this section, two dancers on each side of Manhattan began simultaneously at the current shoreline and walked paths through the parts of the city that are projected to be below annual flood level in fifty and one-hundred years. (1) This section established the performance within the contextual flow of an urban-ecological-meditation-acknowledgement. And the reflection on rising sea levels, future water, dovetailed with Iglesias’s exploration of historic water—water to water.

On the walks, the notion of audience is thrilling. There were the audience members who walked with us and became a part of the first part of the piece. Then there was all of New York City, unwittingly and organically a part of this strange, macabre walk, and all the poetic entanglements that happen day-to-day became a part of the walks.

LR Absolutely. Could you expand on what you mean by the idea of the dance poem, and meditate on the relationship, perhaps, between dance poem, a score, and mapping? These are essential points in giving us a better sense of how to reimagine the cityscape as a core component of this piece, and how it’s been staged.

BBR The first thing I’ll say is that poems really got me through the pandemic. As life becomes increasingly incomprehensible, I think poetry has this ability to somehow parse things together or explode them.

I will quote from two folks. First, a longtime reference, Octavio Paz, says in The Bow and the Lyre (1956): “The word free at last shows all its entrails, all its meanings and illusions like a ripe fruit or a rocket exploding in the sky. The poet sets matter free.”

And the other is James Baldwin. In the 1973 documentary From Another Place—which filmmaker Sedat Pakay made while Baldwin was in Turkey—Baldwin says: “I think all poets—and I’m a kind of poet—are caught up in a situation which is a kind of pre-revolutionary situation, and that they have a very difficult role to play. Insofar as real poets, they are committed to the welfare of the people, of all people, but they don’t always read this welfare as simply as politicians might. My role is to try to bear witness to something that will have to be there when the storm is over, that will get us through the next storm. Storms are always coming.”

I heard this a few weeks ago and thought it was perfect, because Shadow of the Sea is about storms, right? It’s about the shadow of water, the shadow of storms, and the shadow of disasters. I think those two quotes contextualize quite well what a poem or a poet is here.

With the term dance poem, I was thinking about replacing the words in a poem with movement, or gesture. There’s something about dance that simultaneously accesses our biological reality, and also accesses this kind of mythic psychological condition.

In order for the piece to be legible at this scale of the Commons, the choreography had to be lyrical. Lyrical in the sense of the poem, the bard, and lyrical in the sense of succinct expression. This is where the stanzas came in: the piece was structured into eight stanzas. As in poetry, stanzas often organize in quick succession a variety wide concepts. Having Shadow of the Sea unfold in this way gave structure to a range of cosmic ideas.

To touch on your question of mapping and cityscape: the first section, or stanza, of the work, was the coastal walks. As I mentioned previously, that section’s score was based on the reading of sea-level rise projections. It was my first time using a scientific projection as a part of a score, and offering a poetic interpretation through the choreography.

We are a city surrounded by water, and in the next twenty, thirty, fifty, one-hundred years we are going to see vast ecological change. But in some ways the maps, though factual, are so hard to comprehend as a human being. The scale of it, and the vastness of time. Also, maps are never completely neutral, right? There are many worldviews that create the map itself, just in that science is an act of interpretation of data. The coastal walks are monumental in scale and anti-monumental in form somehow.

In my work, the maps meet my score, which liberates the question: What does the body know? What do bodies comprehend, and what can be understood poetically or emotionally through that bodily action that could not necessarily be otherwise?

In Stanza 1, A Brutal Meditation, there are poetic moments, despite the brutality of the premise of the walk—moments of tenderness and care and when the two performers come together and coming apart in their movements. It also captures this unease, this achey thing we all know. Lyrical unease: these are moments where it’s like, yeah, we need each other.

Angelique Rosales Salgado (ARS) You’ve touched on this notion of a prism a few times now, and a prism is an object that can cast many shadows. Could you talk about the title Shadow of the Sea, which evokes one of the work’s central questions: “the sea covers 71% of our planet? And what about its shadow?” What brought you to formulate this question? How did it function as a driving motivation for the piece, not only in your research and in your references, but also as you tried to map it out in an embodied way across the project’s different sites?

BBR This question started with the Paul Valéry poem from 1904–1905 published in Poésie Perdue:

Vois l’ombre de la mer/l’onde/que la lune tourmente Et qui traîne des monts sur sa forme dormante Les monts coulent toujours Dans leur ombre.

Which translates to:

See the shadow of the sea/the wave/that the moon torments And which heaves its hills on its sleeping form The hills falling always Within their shadow.

I was simultaneously destroyed and exploded by this image. It struck such a chord in me. Trying to imagine what the hell the shadow of 71% of the planet could even look like is unfathomable. It felt like: this is the time we’re living in. We’re living in the shadow, the incomprehensibly enormous shadow of things. Of forest fires, of floods, of the Industrial Revolution, of Extractivism, of Extreme Capitalism, of all these things. And you and I, we did not have individual agency over when we were born; we were born into these shadows, these reverberations of all these things.

I read that poem early on during the creation of the piece. Valéry was not thinking about climate change, the Anthropocene age, when he was writing it. The collection of poetry that this poem appears in, Poésie Perdue, is detritus poetry—work that Valéry threw out or hid, that was never supposed to see the light of day. The scholar/editor Michel Jarrety published the compilation in 2000. It felt like this sort of double myth, where there was some supernatural force that had picked up that little piece of paper from the early 1900s, put it in this edition in 2000, and then later put it in my path.

Then, like many things in creative life and art making, once that electricity happened, the shadow just kept coming and coming. After a few weeks, I realized I really needed Manhae and his poetry. If Valéry provided the sort of initial explosive image, Manhae provided the kind of spiritual or universal context of Shadow of the Sea. Manhae is most known for his metaphor of the “Nim” or the beloved, who is always leaving and always departing. “Nim” could be your beloved, or yourself, or your happiness, or the latest extinct species. It is sort of a metaphor for loss and evanescence, but also Buddhist transcendental love. He was writing in a time of immense colonial violence and social upheaval in Korea in the early 20th century. He was one of the leaders of the anti-colonialist movement, an activist, community organizer, feminist advocate, writer of essays and articles, and a poet. He was jailed several times. He was pretty radical. The universal love of Buddhism that we come across now in the West is often really diluted, but Manhae is coming from an almost militant point of view in terms of how this transformational tenderness, the aliveness of life, can actually bend things toward less violence and something more whole.

I prepared a rough translation of his foreword to The Silence of Nim (1926), which I hadn’t read again for years until making the piece. In this, he defines who is “Nim”:

“Nim” is not only the beloved, but all things longed for. If all living beings are the nim of the Buddha, then philosophy is the nim of Kant. The rose’s nim is the spring rain, as Italy is the nim of Mazzini. Not only do I love nim, but nim dost love me. If romantic love is freedom, so also is Nim. However, have you not received the frugal constraints attached to freedom’s good name? Do you also have a nim? If so, it is not your nim, it is your shadow.

So here, in this forward, I was like, “I found it!” The shadow is this unification. It’s a cosmic bond that one cannot escape of interbeing.

In addition to these poetic references, there’s also a physical reality to the shadow that I think is good in terms of it being a metaphor that is understandable.

All of these layers came through in the movement. I think it is important for me to foreground that the movement and the dance language was coming from a non-Western, non-modern dance context. The body needed a lot of space for atmosphere. It needed a lot of time for shadow. It needed negative space gravitas for water to come in and clouds to pass through and things like that. It also needed simplicity, sparseness, directness—again, channeling the efficacy of a glyph.

I explored those references in different ways through the piece, and each stanza was stylistically different. Throughout the piece, the status of the body also evolves: from pedestrian (so, human) to becoming non-human to eventually becoming water or poem or element in the final section. Maybe a dissolving of the human.

AB I’m curious to tie back to something that you said previously, as it relates to the question of the legibility of this piece in public, and how that connects to the nature of the work as a dance poem. One of the things I’d be interested in hearing about is the relationship between the different Stanzas as you’re starting to describe them. Each has a different tone, and as a result the piece ranges quite widely. Could you reflect on what that means for audiences who might be coming in and out of the piece and only experience one or a few of the Stanzas? How might that have impacted viewers’ interpretations of the work?

BBR One thing I was thinking a lot about, going back to the concept of the Commons and legibility, is hieroglyphs and the body being a bard for the public, for the many different ranges of public in terms of class and race, native New Yorkers and visitors, and whatnot. Another thing I’ve been thinking about since COVID is realism, because the more real something is, I think, the more unreal or more surreal it becomes.

I was interested in Shadow of the Sea in making a dance poem that felt real. I think what connects Shadow of the Sea with Performance Paysage and other work, despite how different the tones are, is that I’m interested in providing space for some kind of emotional quality or psychological context in which we can sit for a moment and just together recognize that we’re living through this. Because what we’re living through in the Anthropocene is so strange and catastrophic. One psychological term that always comes to mind is cognitive dissonance. We live in such contradictions. Another term is derealization; studies show that our minds are "derealizing" the experience of climate change as a way to mitigate trauma.

I wanted the piece to capture those contradictions. Therefore, with the range of tones across the Stanzas, I thought it was important to have this kind of like prismatic kaleidoscope, where you have, for example, something very pedestrian in Stanza 1; something more jazzy Stanza 3, A March & A Blues; something quite esoteric and geometric in Stanza 4, X; something more blossoming and eternal in Stanza 5, Insurrection (Big Turtles); something maybe frustratingly stagnant or boring in Stanza 6, Repose (Nature morte); and something more embodied and poetic in Stanza 8, Sea. All of these things exist in harmony together in the piece in a very nonsensical, almost whiplash way.

I was asking, what can this piece do? Perhaps it can provide a space or rite for an hour, where perhaps we can touch our reality through this movement language, these glyphs, the sounds, the spatial arrangements, how we take up space together. In a way that’s gentle but brutal, not weak, and with courage.

ARS Could you speak about how the range of styles and invocations of each of the eight Stanzas comes from not only the movement that’s unfolding inside of each sections, but also the different pieces of music or spoken text accompanying the movement? I know that the song selection charts your personal connections to an intergenerational range of artists with whom you’re in dialogue. Could you address this aspect as well, and the kinds of relationships you have with them—ranging from those with whom you’ve collaborated directly, and others of whom you draw inspiration from at a distance?

BBR I chose the music very carefully. Stanza 3, A March & A Blues features the song B.B. King, “Why I Sing the Blues,” from Summer of Soul Soundtrack: Live at the 1969 Harlem Cultural Festival (2021). This song was important because it references the history of New York City Parks: it was performed as part of the 1969 Harlem Cultural Festival, which was the subject of the recent documentary Summer of Soul (2021, directed by Questlove). In addition to making links with urban history, like this festival, I also wanted to connect to my personal history. Like in Stanza 5, Insurrection (Big Turtles), the track was a piece by Jeremy Toussaint-Baptiste, Big Turtle (2017). Jeremy is someone I have collaborated with on multiple occasions in the past, including in the exhibition Julius Eastman: That Which is Fundamental at The Kitchen (2018). So with that, I was building on my own institutional history with The Kitchen.

The sound designer for the piece Michael Hernandez created the track for Stanza 6 Repose (Nature morte), using the 220 hertz frequency—the frequency at which scientists have found trees communicate.

For Stanza 7, Era of Loss, I chose a song I associate with the US, Nina Simone, “I Get Along Without You Very Well” (1969). Arguably the greatest thing that the US has given the world is Jazz and the American Songbook.

I was interested in making all these webs at various scales intertwine, and in collapsing different eras.

LR To conclude, I would love for you to talk about the idea of the collective within the scope of the performance. Could you reflect about what it was like to work with a range of collaborators throughout the making and production of the piece? What does it mean to move, act, produce, engage, ideate, imagine, or re-world through a collective practice, in lieu of or, perhaps, in intersection with the idea of a singular individual?

I appreciate that in the history of dance, with the notion of the company, there is always this complex and also really wonderful stickiness that engages the possibilities of collective body, individual body—how each are provided space and have opportunities to stand in place of one another. How did you experience that within this process of contribution with your ensemble of dancers, which included Bria Bacon, Cara McManus, Chaery Moon, and Caitlin Scranton, as well as collaborators Mariah Anton and Savannah Jade Dobbs.

BBR You bring up an interesting point that dance is generally collectively authored, because the choreographer is always collaborating with the dancers in their bodies, and often quoting movements made by others. In the case of Shadow of the Sea, some movement is very particular to who I am and how I embody the world. The movement language is my own in the ways it is so glyphic and reduced. However, in the rehearsal process, I left a lot of space open for the dancers to make choices, to inject their own selves and interpretations of the material. Jazz is always a presence in my work. In Jazz, there is riffing, and that ultimately is always collaborative and collective, in that you’re developing something new within the context of a shared vocabulary and artistic language.

With this piece, I was the funnel and the prism through which many voices were shining. The scale of the work, the subject of the work, the Commons of the work, the ambition of the work required so much more than the individual. The Anthropocene, this geological age, and climate change are things we’re all experiencing. Therefore, it’s a universal experience, and in Shadow of the Sea that universality was represented and lived by the cast and the huge team behind it too.

FOOTNOTES

(1) “Land below annual flood level” denotes areas that are predicted to flood on average once per year. The research-based projections are drawn from the Coastal Risk Screening Tool on climatecentral.org. The walk areas currently are zoned high-risk (VE or 100-year Floodplain) by FEMA.

BIO

Beau Bree Rhee (she/they) is a visual artist and choreographer. She works primarily with performance and painting, additionally with scores, drawing, poetry, and installation. Her work centers around body-space-ecologies and radical interbeing. Rhee is trilingual and tricultural (Korean-American-French), based in NYC and Paris. She is invested in collaborative and multi-modal work connecting disciplines such as cosmology, science, myth, literature. Rhee is engaged in "liberation work" - her practice opens life-affirming possibilities beyond the extractive and oppressive systems that created the reality of our environment today. She works with movement, color and ecological practices to create new visual and choreographic languages that express this larger vision.

In 2024 and 2025, she has been working as a laureate artist-in-residence at Cité Internationale des Arts Paris. Rhee has shown her work at institutions including The Kitchen; Madison Square Park Conservancy; Ma’s House BIPOC Art Studio; KW Institute for Contemporary Art; Bard Graduate Center Gallery; Kaaitheater Bruxelles; Baryshnikov Arts Center; MoMA/PS1. Over the last ten years, she has presented five evening-length performances and four solo exhibitions.

Rhee is a part-time Assistant Professor at Parsons School of Design, and has guest lectured at Columbia University, Yale University, The Whitney Museum, Guild Hall East Hampton, and others. She is a grant recipient from the Tishman Environment and Design Center and The New School. Rhee holds an MFA, Haute école d’art et de design (HEAD) Genève and a BA, Art History and Dance cum laude Barnard College, Columbia University.