Credits:

By Rebecca Teich, Writer

July 20, 2023

Jagged movements fill the stage as bodies flail and fall limp into one another’s awaiting arms or ground and steady in jolted motion; ominous drone disintegrations of Kate Bush’s “Running Up That Hill” flood the sonic space; a backdropped projection of ghostly outlined figures fades in and out of view.

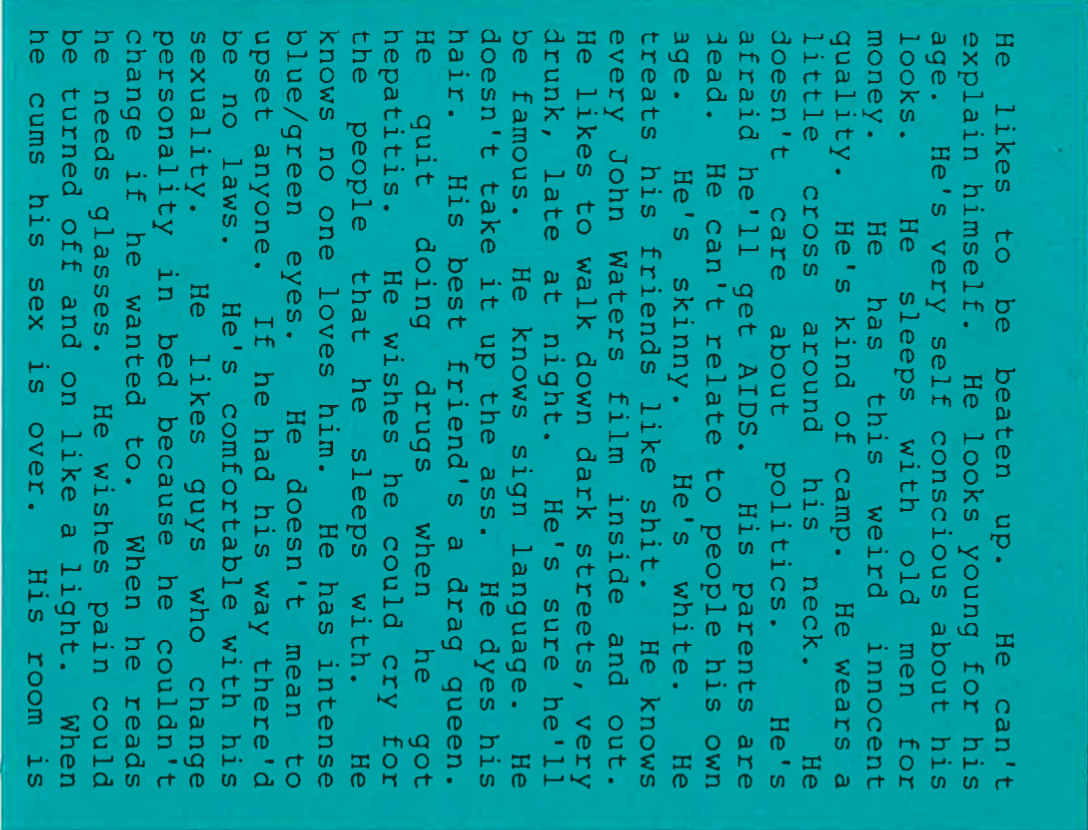

“He wishes he could cry for the people that he sleeps with. He knows no one loves him” (1)

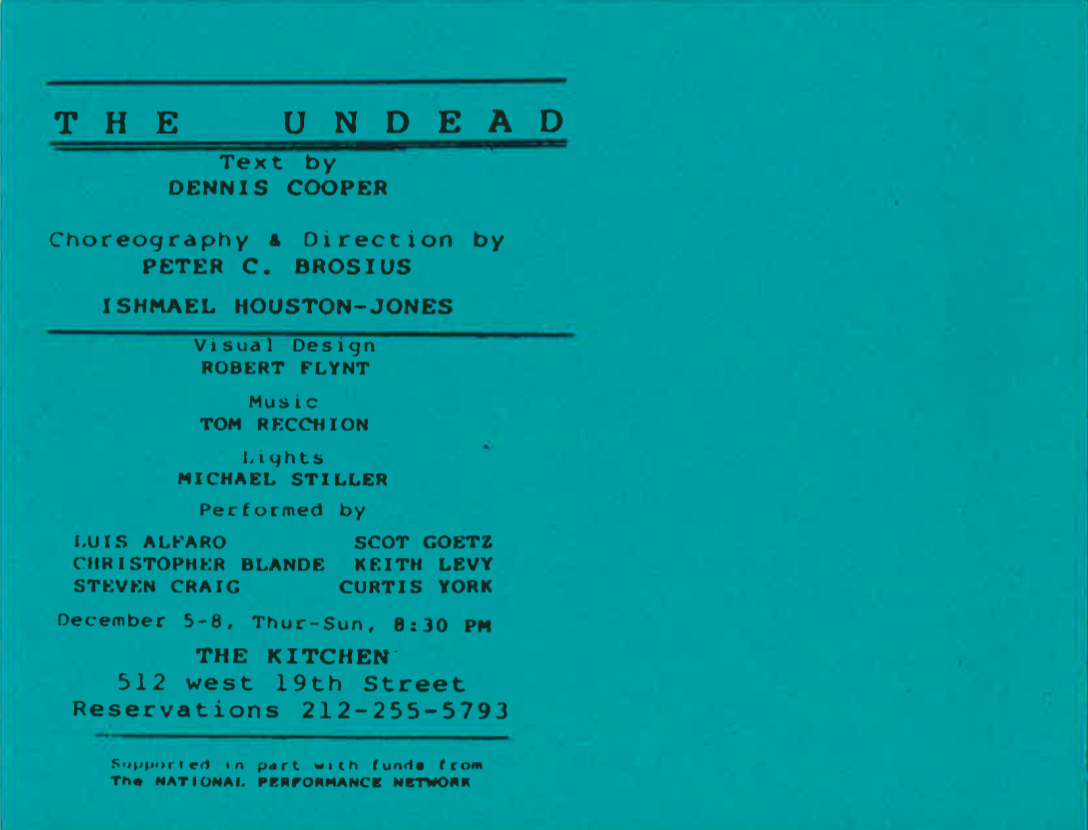

This is The Undead (1990), a performance that splices together text, dance, sound, and visuals by collaborators Dennis Cooper and Ishmael Houston-Jones. Both Cooper and Houston-Jones are legendary figures of queer cult status who have transformed their respective crafts of literature and choreography, yet their collaborative relationship warrants attention in its own right. Their collective body of work includes THEM (first premiering in 1986 and reprised in 2010 and 2018), Hole (1989), and Knife/Tape/Rope (1989). The fourth of their collaborations, The Undead premiered in the Los Angeles Festival of the Arts at LACE in 1990 and was subsequently presented at The Kitchen in late 1991. It would be too simple to say that Cooper lent The Undead its text and Houston-Jones its choreography: rather, collaboration was central to the performance’s production, including the involvement of co-director Peter Brosius, composer Tom Recchion, the photographer/visualist Robert Flynt, and the performers Curtis York, Luis Alfaro, Chris Blande, Scot Goetiz, Keith Levy, and Steven Craig. Following two months of immersive rehearsals, the six performers shaped their respective characters in The Undead based on their own idiosyncrasies and capabilities.

“I want him to get sick so I can take care of him… and I want him to have safe sex and I want him to live forever”

The Undead marked the fifth year of Cooper and Houston-Jones’s collaborative relationship, which developed during a period that saw a horrifying, rising number of deaths due to complications from HIV/AIDS enmeshed with—and in large part resulting from—seemingly endless state negligence and abandonment. Despite this structural silence, the archive of artistic production from this time period resounds with attentiveness, presence, and noise. The archive of performance in particular houses a riotous yet slippery noise, grating against tidier, singular historical narratives that might more easily collapse into the tropes of respectability. Dance performance has a specific relation to the ephemeral: its movements threaten to leave no trace, yet the traces it does leave move. These traces of The Undead live in reproductions splayed across New York City—from the scripts in Cooper’s papers at NYU Fales Library and Special Collections to video recordings in Houston-Jones’s archive at the NYPL Jerome Robbins Dance Division to performance ephemera in The Kitchen’s archive—as well as in newspaper clippings, in memory, and in citation.

The broader backdrop to The Undead ought to be understood as the intertwined collective and intimate experiences of a homophobic capitalist culture of extraction and loss, the underground world of transgressive (2) queer art, and the former’s assault on the latter. Just the same year as The Undead’s initial LA staging, the NEA Four (performance artists Karen Finley, Tim Miller, John Fleck, and Holly Hughes) infamously lost their grant funding when it was vetoed by chairman of the National Endowment for the Arts, Jonathan Frohnmayer, due to pressure from Congress and particularly Jesse Helms. That same year, grantees of the NEA received an amendment to their awards enabling the refusal of federal funding for works that “promote, disseminate, or produce materials that are obscene or that depict or describe, in a patently offensive way, sexual or excretory activities or organs, including but not limited to obscene depictions of sadomasochism, homo-eroticism, the sexual exploitation of children, or any individuals engaged in sexual intercourse.” The extant violence, stigma, and neglect occuring on a national biopolitical level seeped into a targeted attack on queer, sexual, transgressive arts. The government was not just being silent and inactive in their address of the epidemic as entwined with irreducible queer worlds and sex, but it was also actively denying funding, and suppressing artists who stepped out of the bounds of respectable palatability and into the queer, sexual, and transgressive. The Undead’s staging at LACE and The Kitchen situated the performance in the rich company of queer experimental cultural productions communing under the imminent threat of the removal of funding.

These circumstances of The Undead’s production provoke further insights about survival—the survival of individuals struggling to connect under a repressive regime as thematized within the performance and the survival of a work of art made under those conditions. Rather than approaching The Undead as a lost artifact from a bygone past, I want to offer up the performance as a hauntological guide for understanding archival objects living under the sign of HIV/AIDS cultural production and the attendant ongoing, shifting, and overlapping crises of capitalism and homonormativity that eject queerly disreputable individuals and performances stretching into our present.

“Tangled up, spaced out, and really removed”

The Undead mixes queer pop-nihilism with a hypersensorial Gesamtkunstwerk setting wherein monotone language is punctuated by wildly flailing bodies, screen projections, thick musical scoring, and the flash of sex, violence, death, leather, and sequin. The performance revolves around six gay men navigating alienation and loneliness, desire and yearning, who grasp at and fail to hold enduring intimacy steady. The young and alluring Mark—following Cooper’s signature use of stripped down monosyllabic names—is the figure yearned after by the five other players. Mark’s own desires remain open to nearly everyone yet disinterested in anyone in particular. Together the six characters form an ensemble of disreputable queers who are neither lauded as heroes nor castigated as villains. The performance is composed of short vignettes that alternate between scripted dialogue/monologue and wordless, often group, choreography. In the scripted vignettes, characters make attempts to connect with Mark, discuss sex, murder, and pop culture, and muse on their illicit proclivities—each pushing toward the edges of the permissible before their language collapses into gesture. The edges of the permissible collapse with the edges of the body and interaction between bodies, showcasing the punctures and porosities intrinsic to sex, violence, and their overlap.

The edges of the permissible also collide with the edges of the legible. At times the legible sentences of language and dance torque into rhythmic utterance, noise, thrash, and movement. The choreographed sections tread the line between tender embrace and violent scrimmages, with performers tossing each other about in duos and trios. Solo performances often comprise repetitive and seizure-like motions. While there are characters with evoked backstories and discernable driving wants, the vignettes’ ordering does not contribute to a narrative progression, but only weaves further tangles between materialities and abstractions. At one point a character says, “‘Sex is just this bizarre point in the day where things get incredibly scribbly for some reason. Fights are the same way and murders, diseases, stuff like that.” Sex, fights, murder, disease in some ways become equivalent as relational characters within the fabric of the performance.

This invocation of “disease” is not the only instance that the HIV/AIDS epidemic haunts in the backdrop and foreground. The epidemic is palpable, but it is not the sole force shaping alienation, carnality, desire, violence, and sociality within a performance that very much reflects a queerly populated, late ’80s pop cultural universe. In a monologue that was featured on printed material accompanying the performance at The Kitchen, one character rapidfire lists out attributes of a “he” who we might presume to be Mark. One such tagline that is rattled off is: “he’s afraid he’ll get AIDS.” Another overt reference to the epidemic occurs in a dialogue where the two characters go back and forth, quizzing each other on their sexual appetites, with one asking if a potential sexual partner “‘Could… have KS?” When Mark replies “yes,” the other retorts back, “brave.” Less overt mentions of the epidemic populate both the script and the gestures, where concerns over life and death, safety and risk blend and blur. One of Mark’s admirers breathlessly lists a litany of often contradictory fantasies about Mark, speedily uttering, “I want him to get sick so I can take care of him I want my name tattooed on his shoulder and I want him to have safe sex and I want him to live forever.”

These mentions direct and indirect around sexual desire and openness against the backdrop of HIV/AIDS loom palpably over the stage. However the performance refuses a narrow understanding of what might be unsafe, risky, or dangerous sex, and it does so without dividing up those terms into separate lists of morally right and wrong for the individual actors. HIV/AIDS is present as a risk in the type of sex sought out, but it is not the only risk—gestures and signifiers map capaciously and encompassingly around a network of risks taken when pursuing encounters with others. Risk, as well, is not divorced from potential pleasure or even hope—their tricky tango never defects to simplistic moralizing or reductive visions of sexuality, safety, and power.

The Undead isn’t about heroism emerging within a singular crisis, but colliding antiheros and violences that endure beyond rubrics of respectability: low affect, high risk, masochistic, sadistic queer perverts. The Undead snags onto the less glamorous, less sexy, less valiant moments of gay alienation under late ’80s and early ’90s capitalism knitted into a social fabric.

“I'll use the tip of my tongue as a pen and you will have Jane Mansfield’s autograph written in your own shit, Mark”

“The Undead is a Jesse Helms nightmare,” hailed Michael Phillips in The San Diego Union following the debut of the performance in LA. Indeed, the collaboration—across its form, content, and production—would raise Helms’s hackles. Nearly every item enumerated on the prohibitive list of the NEA’s 1990 pearl-clutching amendment is featured, front, center, and in rich ambiguities. Faggotry—neither sexless and respectable, nor politely bourgeois—is in full force and the choreography blurs the line between romantic touch, sadomasochistic sex, collapse under bodily duress, and physical violence. The text does not shy away from age gaps and excrement. The characters reckon with how far they can, should, and do chase sadomasochistic yearnings as well as interpersonal and impersonal connection, amidst choreography that moves from a gentle hold into a tense headlock and back again. There is no resolve.

Thematizing without moralizing the very characteristics the NEA amendment enumerated as obscene, The Undead emblematizes transgressive queer cultural production in its formal stylizations and content around HIV/AIDS and the communities impacted by the ongoing crisis amidst a dominant culture of silence and conservative cultural backlash. It is not only that HIV/AIDS haunts the performance, but also that the performance realizes how governmental negligence, capitalist alienation, and respectability haunts HIV/AIDS culture and production. The legacy of government backlash against aesthetic production has shifted but certainly not evaporated today. There, too, is no tidily resolved ending but an enduring antagonism.

The Undead occasions us to reflect on how we regard queer artistic production from that time period from the vantage point of a present moment that seems keenly attuned toward looking back to such art. (3) Dangers of reproducing, recollecting, and revisiting arise when relegating a past to a neatly finished or dead moment, rather than exploring its “undead” hauntologies and continuities. In a time when many artists who passed due to HIV/AIDS related complications, underrecognized during their lives, are getting post-mortem and post-PrEP re/visitation by the art world, a return to The Undead might refuse to relegate such works to a bygone historical past, to instead view that cultural production as itself “undead.” It is notable that both Cooper and Houston-Jones are still living and producing new work—to sit with their work across time is to sit with their survival as well.

“Haunted people are great. I’m one, that explained the attraction.”

Even amidst its thematization of alienation and disconnect, The Undead is suffused with messy contact that refuses to congeal into the neat categories of strangers or lovers, fighting or fucking, alive (present) or dead (past), language or gesture, narrative or abstraction. The living actors have a ghostly presence, at times fading out of view through the use of lighting and fog, while the presence of enduring machinations of death and violence are rendered palpable through the evocative yet often nonspecific language of death, disease, and danger and the recurrent choreography of fainting, dragging bodies across the stage, and dueted fights. Characters’ alienations and ailments stick to and go beyond a specific cause, refusing simple answers or linear resolutions that we typically demand from narrative, that we typically demand from the past. The performance invokes and provokes us to sit with these layered hauntings. Such hauntings burst from their temporal frame to resist the safety of the past tense. The performance’s antinarrative occupies a perverted, enduring present that also perverts notions past and future.

Relegating HIV/AIDS to the category of the historic past, rather than the still-present, still-living, and undead, inaugurates another kind of silence—conjoined with but nuanced from the initial deadly silence by state officials refusing to address the epidemic—that erases the ongoingness of the epidemic and the structural disparities around race and class that have shaped access to care and recognition throughout. To haunt is to refuse such absentings; to haunt makes something more than present.

“The world has become such a dark dark dark place for the adventurous”

Both within and beyond the performance’s diegetic frame, the stakes of queer transgressive cultural production are laid bare. Performances such as this put pressure on how we understand the permissible, the respectable, the possible, within a nation and dominant culture that thrives on neglect, austerity, and silence, that power washes queerness with a family-friendly gloss. Here, perverts, in all their complexities and amidst deadening structural conditions, move about center stage. The Undead collides pleasure and violence, desire and no release, collaboration and alienation to point not just toward a culture deeply affected by an epidemic, but toward an epidemic shaped by a broader culture of structural abandonment, negligence, and violence. Senator Helms haunted transgressive cultural production and The Undead could have haunted Helms’s dreams to turn them into nightmares.

The Undead haunts and befuddles the very categories of past and present—such that returning to the performance through its documentation illuminates this instance of state repression and queer aesthetic production not as resolved past limited to bygone Regan and Bush eras, but as a microcosm of an ongoing antagonism between what theorist José Esteban Muñoz might term the “stultifying heterosexual present” and a haunted queerness that cannot bear that present. (4) The performance’s characters, screened projections, and drone sonics haunt the stage, and its mode of collaborative queer production haunts that haunting—we sit with the tension between cultural production that points at the totalizing effects of repression while refusing them through collective process. In inhabiting moments of tension—linguistically, choreographically, thematically—rather than resolve, the performance attends to what is undead, what remains unresolved, what tensions linger even as they shift out of frame. In so doing, the conditions of production and stagings of The Undead insist on raising aesthetic hell.

BIO

Rebecca Teich is a writer, curator, and PhD student in English at the CUNY Graduate Center. Currently the co-curator of Desperate Living Reading Series with Ry Dunn, Teich curated the Fall 2018 and 2019 Segue Reading Series, and was Artists Space's teaching-poet-in-residence 2019–2021. Teich's writing has been featured in The Kitchen Magazine; Peach Magazine's anthology series, Invitation to Form: Epic Mix; poets.org, Nightboat's Resonance*, The Poetry Project Newsletter, and elsewhere. Teich’s first chapbook, Caffeine Chronicles (2021), was published by Portable Press @ YoYo Labs.

FOOTNOTES

- All italicized quotations are from The Undead, transcribed from the December 1991 performance at The Kitchen, on view at NYPL Dance Division Archive.

- I use the adjective “transgressive” not to function as a vague catchall for strange but to demarcate aesthetic works that exceed (or transgress) specific rigid boundaries of political and aesthetic conservatism’s mandate of respectability, particularly those set by NEA amendment that passed the Senate and House in 1989 and was sent to NEA recipients in March of 1990.

- For more on the revisitations of HIV/AIDS culture re/production and its archive, see AIDS and the Distribution of Crises, eds. Jih-Fei Cheng, Alexandra Juhasz, and Nishant Shahani (Durham: Duke University Press, 2020); Theodor Kerr and Alexandra Juhasz, We Are Having This Conversation Now: The Times of AIDS Cultural Production (Durham: Duke University Press, 2022); Maxe Crandall, The Nancy Reagan Collection (New York: Futurepoem, 2020); and Marika Cifor, Viral Cultures: Activist Archiving in the Age of AIDS (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2022); among others.

- José Esteban Muñoz, Cruising Utopia: The Then and There of Queer Futurity. (New York: New York University Press, 2009), 49.