On View: June 20

The Video Viewing Room series presents recent video works and archival recordings. This online initiative revives The Kitchen's longstanding Video Viewing Room—a dedicated space within our buildings from 1975 through the early 1990s.

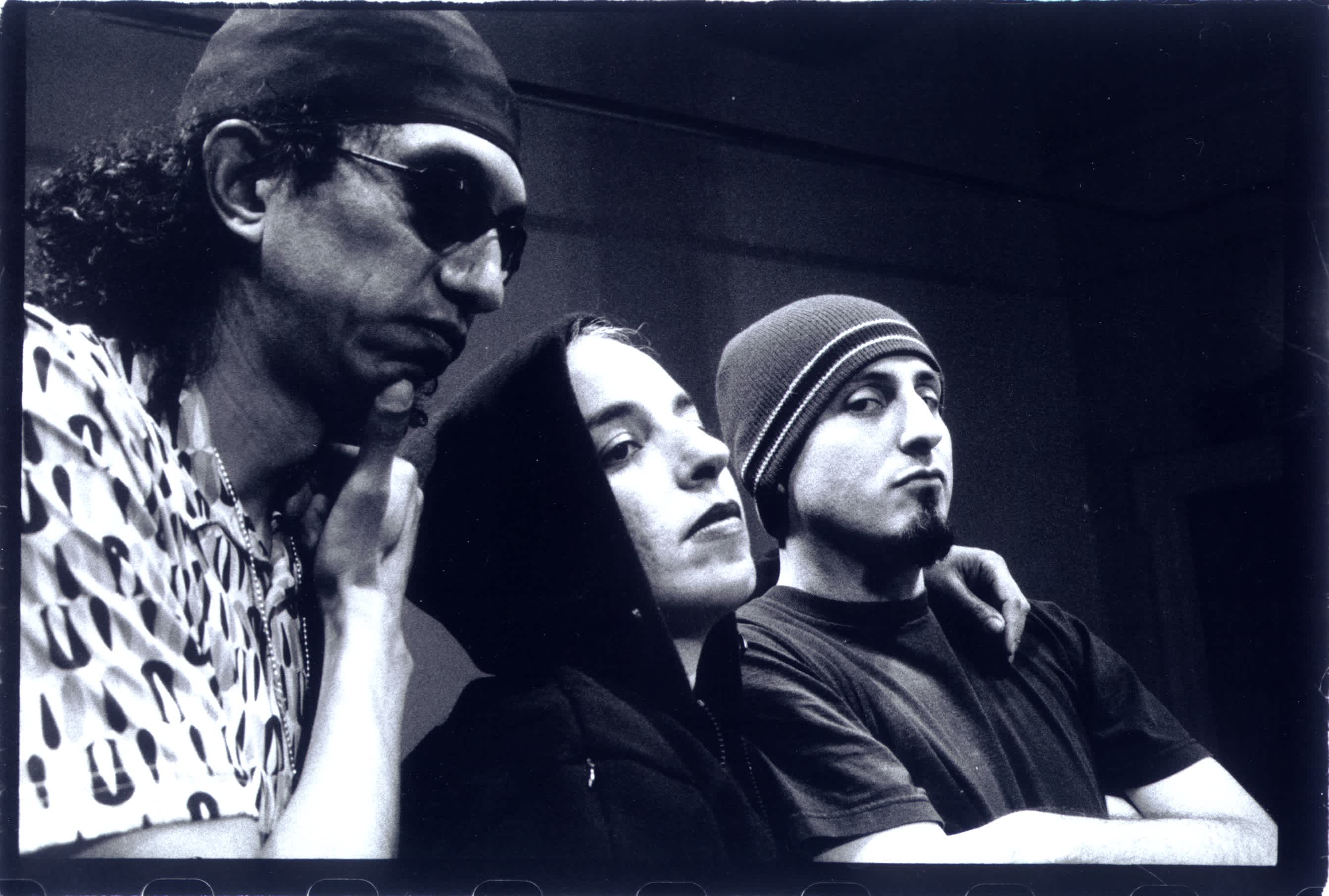

This Video Viewing Room presents three short video works THE GLOBAL WARMAQUINA: The Internet and Its Discontents (2001), El World Brain Disorder: surveillance.control.pendejismo (2002-2003) and TEch TV (2003) by Los Cybrids: La Raza Techno-Crítica—a collective of three artists René García, John Jota Leaños, and Praba Pilar active from 1999–2003 in the San Francisco Bay Area, alongside select photographs from the artists’s archive.

This presentation is accompanied by a text written by Angelique Rosales Salgado.

Los Cybrids: La Raza Techno-Crítica is organized by Angelique Rosales Salgado, Curatorial Assistant.

“THE POWER IS TURNING,” a protest poster reads in the video El World Brain Disorder: surveillance.control.pendejismo (2002-2003). The potential to transform power transfixes Los Cybrids: La Raza Techno-Crítica—a collective of three artists René García, John Jota Leaños, and Praba Pilar who explore cultural and somatic mutations caused by advanced information technologies. Active from 1999–2003 in the San Francisco Bay Area, they refer to themselves as a junta (Spanish for group, often in the context of political revolution) who instigates critical dialogue around access and desire in cyberculture.

In response to society’s fascination with the proliferation of the internet in the late ’90’s, and the expansion of Silicon Valley, García, Leaños, and Pilar formed the collective to enliven their existing criticism about the ever-evolving “digital divide” and the simplistic rhetoric in mainstream media concerning it. The “divide” in question refers to the gap between those who have ready access to computers and the internet, and those who don’t. Within this gap is where the group’s criticism lingers most—in the convergence between online engagement and life offline.

To shape their critical impulse, Los Cybrids reformulate “cyberspace” as an artifact and archetype for access/desire, body/space, culture/globalization, and surveillance/freedom. A “cybrid” is a Latine digi-tech artist from an ethnic demographic disproportionately under-represented in the cyberworld.(1) The group’s name combines “cyborg” and “hybrid” in dialogue with the term “la raza,” which has its origins in post-revolution Mexico and in the U.S. Chicano Movement of the 1970s. (2)The result emphasizes both a racialized and cyborgic body, considering perhaps a type of mestizaje networked with the technologies that are the very source of their criticism.(3) In adapting this name, their hybridized identities begin to interfere with the white-male middle-class subject as the prototypical “body” that these advanced technologies are designed for. The "doubleness" produced by hybridity here isn’t necessarily in reference to specific people, but as scholar Diana Taylor argues, to “signs, systems of power, spaces” that help explain how colonial authority gets produced, performed, and sustained.(4)

The artists' psychic investment in these archetypes becomes personified in their employment of performance, “burla” (mockery), and multimedia as both engagements and provocations. Los Cybrids’s 1999 manifesto, “Cybridnetics: an Ese from the Other Side of the Digital Divide” sets out to to refute the “cryptoreligious myths” of access and utopia accompanying technological invention.(5) “This is not an encounter with technocratic fantasies, utopian visions, nor rendering of maleficent technological dystopia,” they write, “it is a counteroffensive against the mili-corp monoculture that evolves and promotes Information Technology to stifle critical voices.”(6)

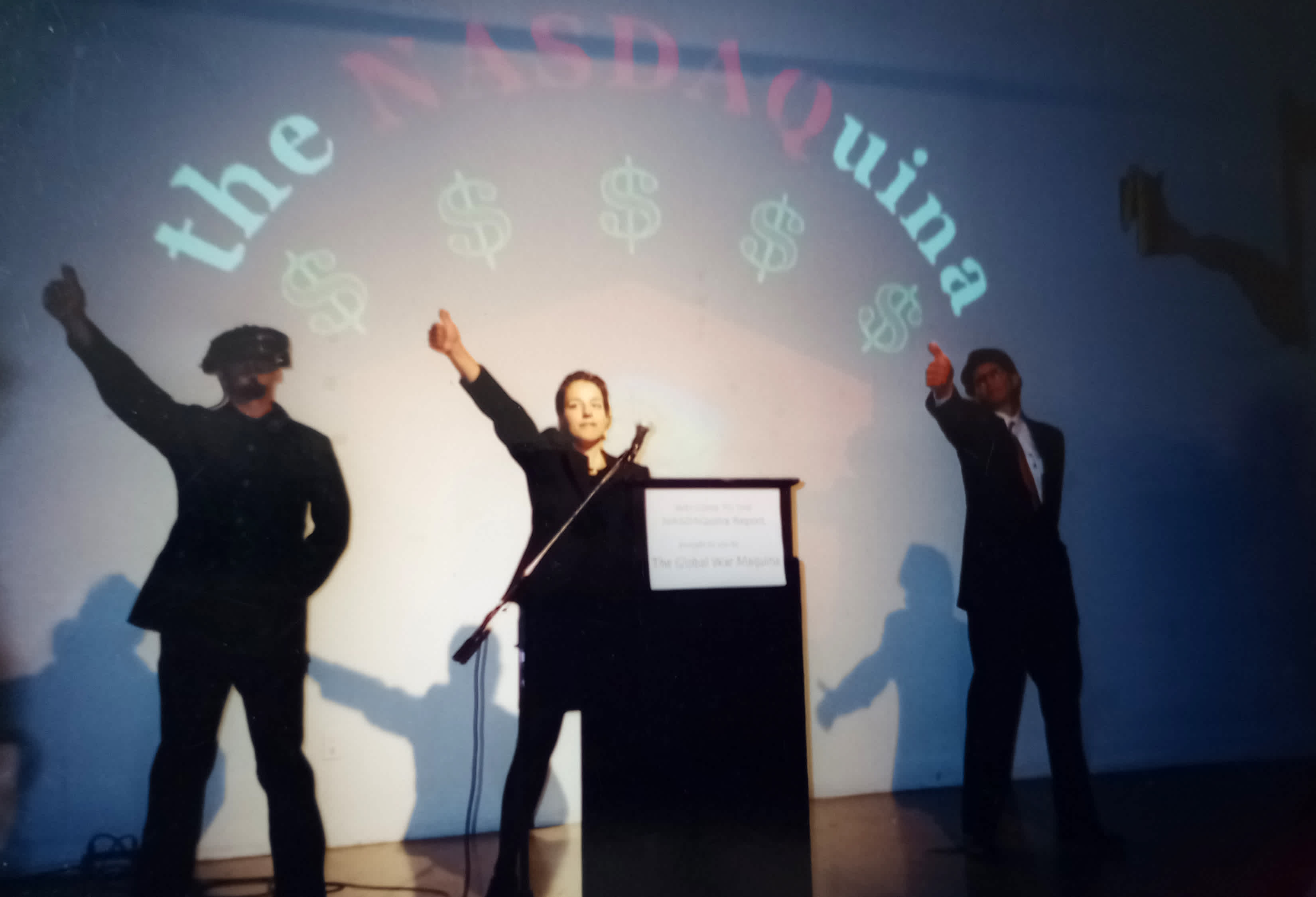

THE GLOBAL WARMAQUINA: The Internet and Its Discontents (2001) parodies how surveillance, environmental degradation, and militarization are at the forefront of a wave of globalization newly enabled by information technologies. Footage of then-president Bill Clinton and the United States Congress cuts to clips of anti-globalization (WTO) and union labor protests colliding with police violence. Simultaneously we see García, Leaños, and Pilar performing as figureheads in the “investors fiscal year-end and state of the globe report on the state of high-technology investment.” (7) It feels like the prelude to a board-meeting-cum-lecture-performance where the artists take the stage to praise the spread of digital capitalism and global capital investments.

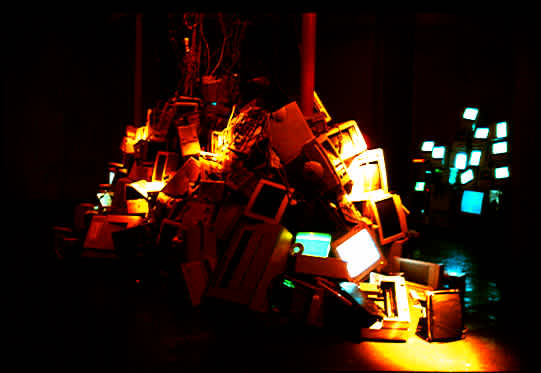

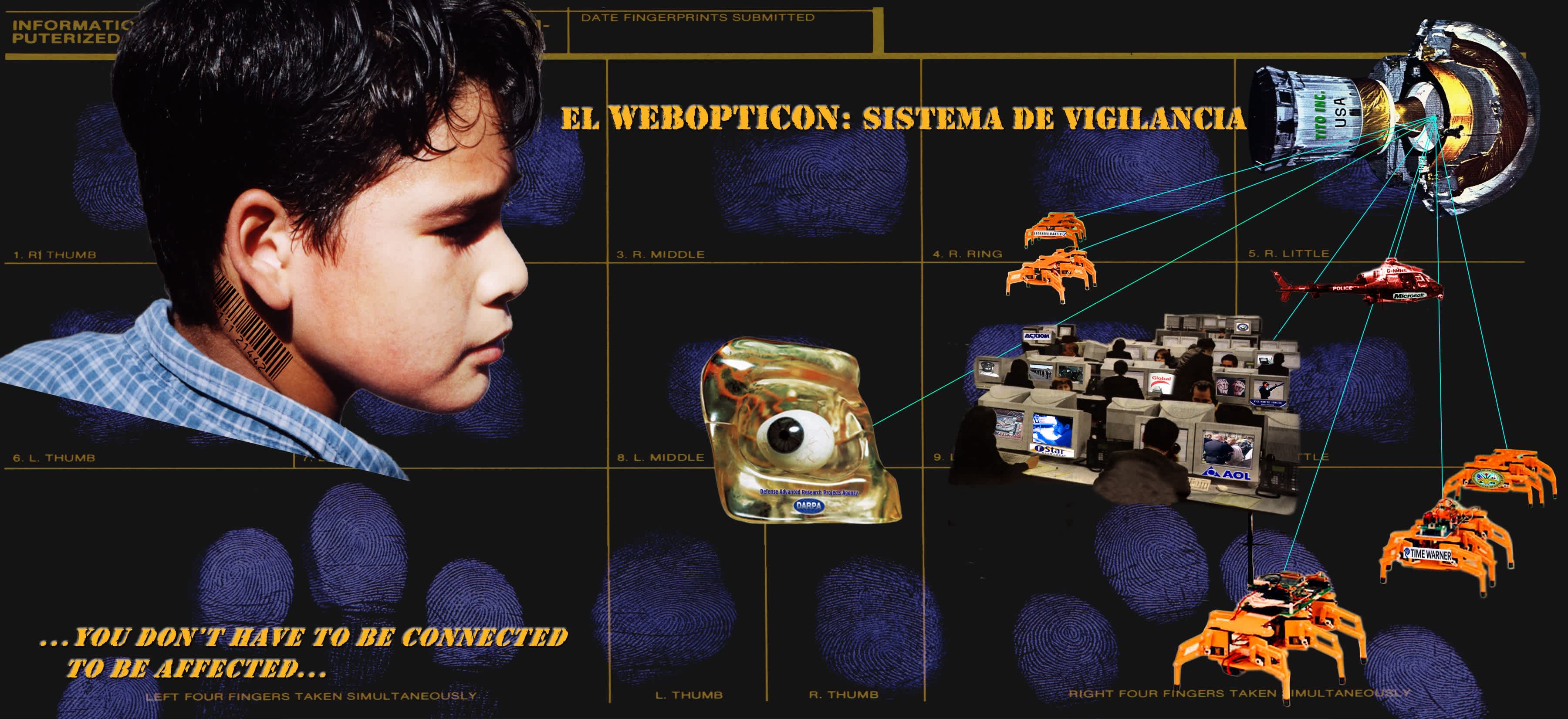

El World Brain Disorder: surveillance.control.pendejismo (2002–2003) similarly satirizes how sanctioned militarization and social reorganization is inherent within the declaration of a “New World Order.” First coined by the Bush administration in 1991 after the Gulf War in Iraq, the term proposes a unilateral global system of cooperating liberal democracies. The fast-paced video montage of national security footage, sniper cameras, and data tracking software unfolds like a mash-up of a “we interrupt this program” broadcast, a system-reboot pop-up window, and a video game commercial. Ironically, a drum and bass-esque remix of the track “It’s a Small World” by Richard M. and Robert B. Sherman scores the video, implicating the internet’s non-stop wireless connectivity as a source of both unrestrained access and unforeseen commodification.

Los Cybrids’s 2001 essay “Webopticon: Aquitectura of Control” deems this interconnectivity as the “latest weapon in continuing war on the poor and communities of color.” (8) In dialogue with the inclusion of pendejismo (assholery) in the video’s title gets at the inattentive colonial unconscious of American society that justifies colonial extraction, genocide, and imperial warfare within a perpetual splitting of humanity along racial lines. They name digital red-lining, racial profiling, security cameras, location tracking, and the Automated Biometric Identification System (IDENT) for storing and processing biographic information for national security as real-life examples. What bears the imprint of these advancements more broadly, they note, is the privatization of prisons, and the accelerated rate in which Black people are incarcerated in the United States.

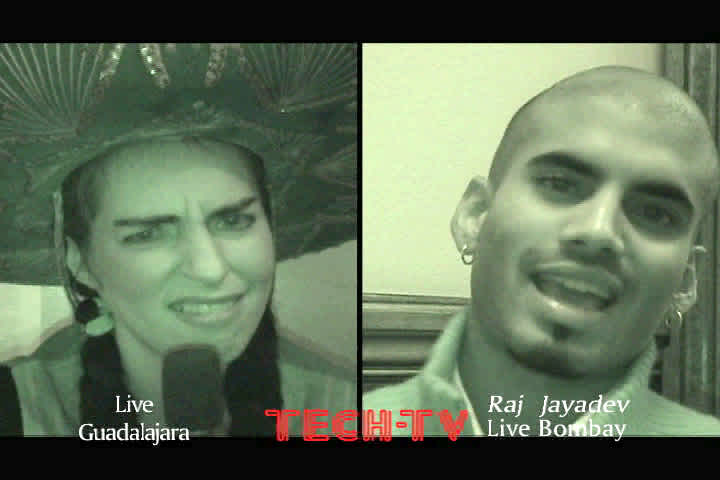

The group’s vision continues to surge through an exaggerated type of burla (mockery) that is quintessentially Mexican. This sensibility—rife with wordplay, double entendres, and verbs modified as adjectives—is particularly idiosyncratic, shady, and often spills into themes that might be deemed “politically incorrect.” While silly to try to capture an affect / effect that is deeply social and culturally-specific within the limits of the English language, Los Cybrids democratize this sense of humor by attending to how its meaning and liveness might serve as forms of study. The video Chicano, Chicana, Latino, Latina, Hispano, Hispana: TEch TV (2003), as they call it, is “the only show dedicated to Latinos in advanced technology.” The show is frenetic, mixing news updates and emotional stories with slapstick comedy, unfolding like the late-night Univision Spanish-language television program called Sábado Gigante. (9)

The video’s score elaborately mediates the work’s tone, however unserious, with the inclusion of two popular Spanish-language tracks: “Gimme Tha Power” by Molotov, a Mexican rock band best known for their political satire and social criticism towards the Mexican government, as well as “Maligno” by Colombian rock band Aterciopelados, a song about an internal battle with a destructive force (likely, a lover) that has embedded itself within the narrator's psyche. The song goes on: "Tiñes mis días de fatal melancolía / You tint my days in fatal melancholy [...] Eres el hacha que astilló toda mi vida... / You're the axe that splintered my entire life." The track suggests a loss of control and autonomy, here layered onto a clip of an animated Aztec character endlessly staring at their screen, who is afflicted by a deep sense of melancholy.

Juxtaposing and reworking language for the purpose of political reorientation aligns with Mexican/Chicano artist, writer, activist, and educator Guillermo Gómez-Peña’s transdisciplinary arts organization, La Pocha Nostra, founded in 1993, which is concerned with polluting, “browning,” and infecting web space.(10) Peña’s group, invoking revolution and resistance through reference to the Zapatistas group, develops pedagogies for resistance that theorize on alternative Latine “cyber-barrios,” “ethno-cyborgs,” and “cybervatos.” Los Cybrids’s politicization of both language and humor happens when Spanish imposes upon English, exemplifying a sort of intervention on the understood lingua franca of the internet.

The artists, who share a decades-long friendship, often refer to themselves as “cyberputos.” Within their performance scores, video scripts, and writings they often inscribe the word “puta” or “puto” onto machinic technologies and the prefix “techno” onto referential nouns. For instance, “computa” to refer to computer, or “tech-aztecas,” “techno-santeros,” “techno-promesas,” and “techno-criticones.” In this context, “puto/a” becomes a proxy for how technology implicates the body between labor and desire, while “techno” claims a bind on technological determinism. Ciphering between the two is playful, but it also deepens their explorations around desire versus persona, fantasy versus confession, performance versus invisibility.

This betweenness performs disidentification, what Jose Esteban Muñoz calls the work of imagining a reconstructed narrative of identity formation that locates the enacting of the self at precisely the point where the discourses of essentialism and constructivism short-circuit.(11) As a collective proposition—a reformation—within this framework of performance, Los Cybrids give into, participate in, and enable advanced information technologies in order to destabilize them—conditions so often characteristic of both world making and survival.

FOOTNOTES

(1) Los Cybrids: La Raza Techno-Crítica, “Cybridnetics: an Ese from the Other Side of the Digital Divide,” tripwire: a journal of poetics volume 6 (2002): 108. (2) The Spanish expression “la raza” ('the people' or 'the community'; literal translation: 'the race') has historically been used to refer to the mixed-race populations (primarily though not always exclusively in the Western Hemisphere), considered as an ethnic or racial unit historically deriving from the Spanish Empire, and the process of racial intermixing during the Spanish colonization of the Americas with the indigenous populations of the Americas. The term was not widely used in Latin America in the early-to-mid-20th century but has been redefined and reclaimed in Chicanismo and the United Farm Worker organization since 1968. This terminology for mixed-race originated as a reference to "La Raza Cosmica" by Mexican philosopher and politician José Vasconcelos, although it is no longer used in this context or associated with "La Raza Cosmica" ideology by Mexican-American, Native rights movements and activists in the United States. (3) According to the Oxford Reference dictionary, mestizaje refers to racial or cultural mixing and is a principal theme in the valuation of national and cultural identity in Latin America and the Caribbean. It did not come into usage until the 20th century; it was not a colonial-era term. https://www.oxfordreference.com/display/10.1093/oi/authority.20110803100152614 (4) Diana Taylor, “Memory as Cultural Practice” in The Archive and the Repertoire: Performing Cultural Memory in the Americas (Durham, North Carolina: Duke University Press, 2003) 108. (5) The word Ese, Spanish slang for dude or bro, embraces a sort of liminality here, becoming analogous with the word essay. Los Cybrids: La Raza Techno-Crítica, “Cybridnetics: an Ese from the Other Side of the Digital Divide,” tripwire: a journal of poetics volume 6 (2002): 110. (6) Ibid. (7) Performance score, Los Cybrids: La Raza Techno-Crítica, THE GLOBAL WARMAQUINA: The Internet and Its Discontents, 2001. The Lab, San Francisco. Courtesy of the artists. (8) Los Cybrids: La Raza Techno-Crítica, “Webopticon: Arquitectura of Control,” PO’ Press, a project of POOR Magazine (2002): 17. (9) Sábado Gigante is a three-hour program aired on Univision each Saturday since 1986. It is Univision's longest-running program and the longest-running television variety series in world television history. (10) Guillermo Gómez-Peña, “Confessions of a Webback,” Wired Magazine, January 1, 1997, https://www.wired.com/1997/01/ffpena/. (11) José Esteban Muñoz, “Introduction” in Disidentifications: Queers Of Color And The Performance Of Politics (Minneapolis, Minnesota: University of Minnesota Press, 1999) 5.

Video Viewing Room was initiated with the support of the NYC COVID-19 Response and Impact Fund in The New York Community Trust; annual grants from Lambent Foundation Fund of Tides Foundation and Howard Gilman Foundation; and in part by public funds from New York City Department of Cultural Affairs in partnership with the City Council and New York State Council on the Arts with the support of Governor Andrew Cuomo and the New York State Legislature.