On View: May 16

The Video Viewing Room series presents recent video works and archival recordings. This online initiative revives The Kitchen's longstanding Video Viewing Room—a dedicated space within our buildings from 1975 through the early 1990s.

This Video Viewing Room premieres an excerpt of Olukemi Lijadu's forthcoming feature Sister Sister (2025), an impressionistic portrait of Yéyé Taiwo and Kehinde Lijadu, the legendary music duo The Lijadu Sisters.

The film is paired with Lijadu's recent sound composition Mind Baby (2024), a sound work comprising three pieces of reimaginings of the lullaby / folk song “Brown Skin Girl” sung to Lijadu by her Jamaican grandmother, created as part of Alvaro Barrington's Tate Britain commission Grace, alongside sound-based works by artists Femi Adeyemi of NTS, Kelman Duran, Devonté Hynes, Naima Karlsson and more.

From January–April 2025, Lijadu was the inaugural resident at Magnet—an artist-in-residence program and satellite project hosted by non-profit arts organization Speciwomen that welcomes artists based outside of New York City, partnering with 99 Canal to provide private studio space. Lijadu’s residency at Magnet focused on deepening her research surrounding the project of her upcoming film Sister, Sister.

This presentation is accompanied by a text written by Angelique Rosales Salgado.

Olukemi Lijadu: Two Hundred Years Together is organized by Angelique Rosales Salgado, Assistant Curator.

Olukemi Lijadu, Mind Baby, commission for Alvaro Barrington: Grace, Tate Britain, 2024

“I keep saying: to speak is to touch.”

Harmony Holiday, MAAFA (2022) (1)

“But, what does language have to do with the street?”

Renee Gladman, The Sentence as a Space for Living: Prose Architecture (2019) (2)

Olukemi Lijadu fixates on the contours of voice. Inflections inherited, bound up in stories interwoven through improvisation, recitation, repetition. Lijadu is a filmmaker, DJ, and composer, based between London, U.K. and Lagos, Nigeria, who stages conversations with images and sound as installation, both by transforming the scores of her filmic works into live performance and by creating sonic landscapes for her images to exist.

In the circuit of speech, artist Lyle Ashton Harris often begins any discursive public address—a conversation, a lecture, a live program—by asking, “Can I be heard?” It is a remark he simply re-works from the question commonly articulated as “Can you hear me?” or “Can you hear this?” Harris’s consideration of vocality here, arranged newly, exceeds the rhetorical moment of his ask and lingers on durational encounter. “Can I be…” His statement indexes the voice but emphasizes full embodied presence, demanding we turn toward a better disposition of viewing the unknown: arrival. In his life, artistic practice, and frequent use of portraiture, Harris excels at resituating our relationship to the positionality of “I” with regard to “you,” exploring the intimate frictions between dissonance and identity.

Portraiture in its many forms, after all, is an extension (prolonging) of life. What does the voice know about the body, anticipate of it? What of tension, failed speech, silence? How much voice? How much presence? In multiples, a chorus, active or deferred, fleeting, memorialized, undaunted, necessarily queer? Through familial lineage and matrilineal kinship, Lijadu orbits Harris’s musing, uncovering the ways voice, image, persona, and movement become collective sensation. With familial roots in Nigeria, the Caribbean and Brazil, Lijadu invests in sound and diasporic music as transcendent conduits of memory and reconnection across the Atlantic, asking: How have West African polyrhythms and patterns been preserved and transformed into Black American music? How has this reformulated and constructed our understanding and conceptions of modernity and time? The artist’s experimental approach to music and the moving image is informed by the Yoruba philosophical principle of complementary dualism. It is a world sense distinct from the Western Aristotelian binary dualism; one that sees opposing forces or concepts not as conflicts but as inherently interconnected and complementary, foregrounding duality not as separation but as unity. Yoruba cosmology holds this perception as profoundly embodied in the revered significance of twins, or “Ibeji,” who carry a uniquely divine connection and are seen as embodiments of the orisha Shango’s power and favor.

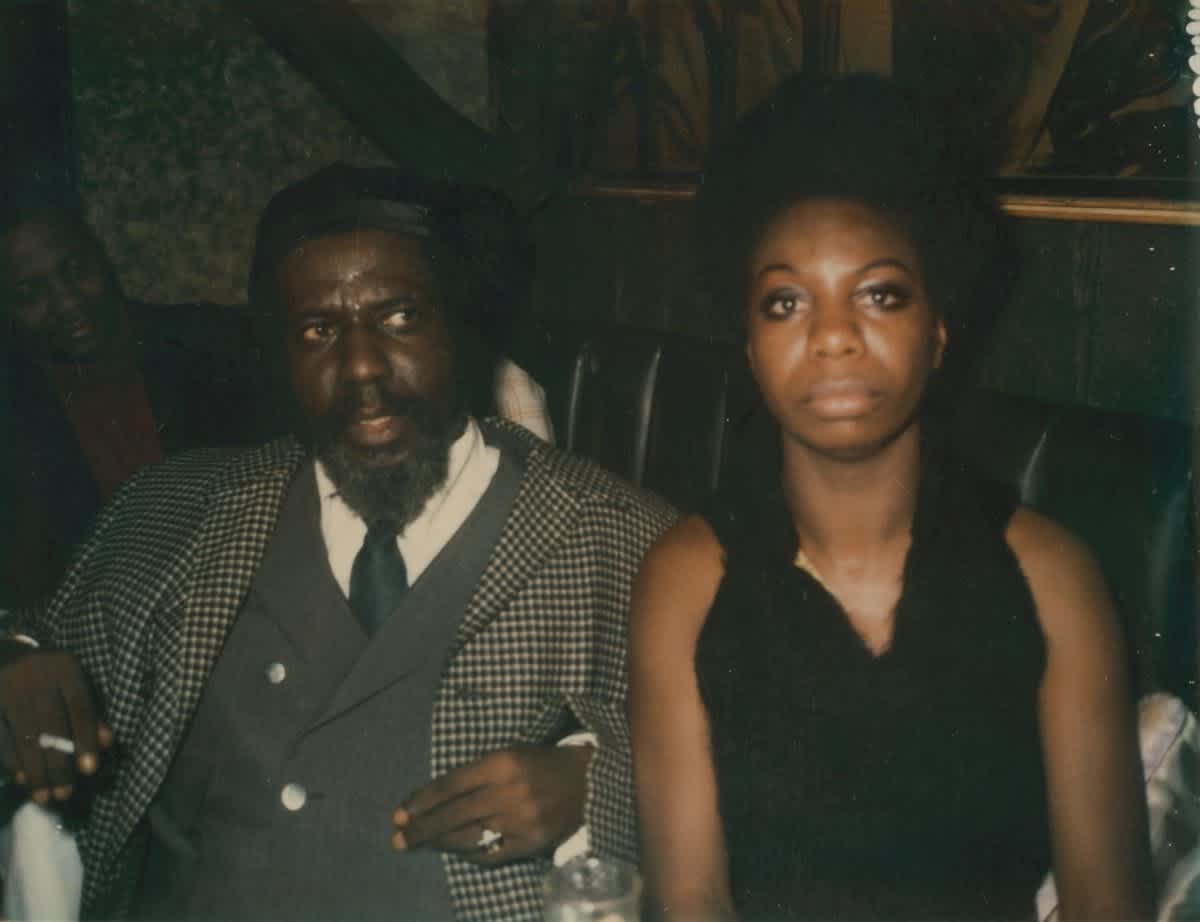

In the excerpt of her forthcoming feature Sister Sister, Lijadu perceptively constructs and anchors this consciousness as moving-image, documenting since 2018 her twin aunties, Yéyé Taiwo and Kehinde Lijadu of The Lijadu Sisters. The legendary music duo, who call New York home since the late 1980s, began releasing music in 1968 and by the mid-1970’s were among the most celebrated and influentially dynamic artists of the era as pioneers of Nigerian pop, combining Nigerian juju and apala music with soul, reggae, rock, disco, and Afrobeat. Lijadu’s teaser excerpt opens with a radiant image of the both sisters standing side to side, singing “O san ka sun re mi” (a Yoruba phrase that means "I am well") that rouses a sense of recurring, cosmic doubling. The work moves like Adam Pendleton’s evocative video portraits (of Lorraine O’Grady, Ishmael Houston-Jones, Yvonne Rainer), which rather than render his subjects in a straightforward documentary address, create a kind of collage of ordinary encounters intercut with personal memory, sonic echoes, and an intergenerational sense of meditation and conversation.

Behind the lens, Lijadu’s tender sensibility searches for her aunties as much as it finds dialogue in imaging the close intricacies of shared body language as communication. Moments of sisterly embrace—Yéyé Taiwo and Kehinde looking intently at each other, Kehinde delicately tying a necklace on Yéyé Taiwo’s neck, the two exchanging a mischievous giggle—emerge interspersed from the foreground of a quiet, black screen. Between sight and sound the frame returns again to a luminescence reminiscent of Alice Coltrane’s 1980’s television broadcast Eternity’s Pillar. Lijadu’s accelerated visual pace, rich lighting, and dramatic close-ups carry narrative, yet dually invest in a sense of shared fugitivity. To call upon Greg Tate’s words, reflecting on the work of Ming Smith: “A fugitivity that is not bound up with escape but a kind of self-illumination.” (3)

We hear whispers of the artist’s voice continue to tune the emotional force of the psychic interior she has constructed to keep their legacy. The film itself is dedicated to Kehinde, who passed in 2019. Yéyé Taiwo and Kehinde’s voices, often intertwined, speak in rhythm, elegantly magnified by Lijadu’s score that resonates in the fold of their shared echoes. Together, their speech harmonizes doubly and their expressions and intimacy revel in the surround—a dream-like oral history that attends to the incommensurability of an entire lifetime, spiritual and social. “Rather than tell the definitive story of my aunts in all its impossibility,” Lijadu says, ”I seek for this film to be a way for the audience to experience them alongside me, not looking for truth per se but rather something more akin to Werner Herzog’s concept of ‘ecstatic truth’.” (4) What emerges from the stirring footage of the two sisters together before Kehinde’s passing, will progress into following Yéyé Taiwo as she finds her voice again, reclaiming her sound in preparation to perform solo for the first time. As the film teaser concludes, we hear Yéyé Taiwo sweetly proclaim: “I love my sister. And I know… We have two hundred more years together…” Prescience is a promise. Lijadu illuminates, “Each person contains a world, and two begin to create a universe.” (5)

BIO

Olukemi Lijadu is a visual and sound artist who works with the moving image, philosophy, and music. Lijadu DJs under the moniker Kem Kem. She uses the power of cinema to take viewers on audio-visual journeys of reconnection across the Atlantic. Lijadu approaches music as a living archive of communal memory and lost connections—critical given the fractured history of the Black diaspora worldwide. With heritage from Nigeria, the Caribbean, and Brazil, the impetus of her artistic practice is both personal and political. Her academic training as a philosopher deeply informs her experimental approach to an ever expanding practice—she holds a bachelor’s and master’s degree in philosophy from Stanford University, where she wrote her thesis on Yoruba metaphysics.

Solo and group exhibitions have been V.O Curations, ICA London, Marian Ibrahim Gallery Chicago, and Manifold Deluxe at Frieze Cork Street London. She was selected as a 2024 Villa Albertine resident where she explored the connections between Chicago House and West African music. Most recently Lijadu also completed the New York based Magnet residency with Speciwomen. During which time she screened her films at The Metrograph. Kem Kem has performed at a number of international art institutions, including Tate Britain, Serpentine (London), Bozar Museum (Brussels), La Gaite Lyrique (Paris), and the National Museum (Lagos). Lijadu is currently based between London, UK, and Lagos, Nigeria.

FOOTNOTES

(1) Harmony Holiday, MAAFA (New York: Fence Books, 2022), 68. (2) Renee Gladman, “The Sentence as a Space for Living: Prose Architecture,” tripwire: a journal of poetics volume 15 (2019): 95. (3) Greg Tate and Arthur Jafa on Ming Smith’s “Acts of Love” in Photography in Ming Smith: An Aperture Monograph (New York: Aperture, 2020), 225. (4) Olukemi Lijadu, Angelique Rosales Salgado, personal communication, May 2025. (5) Olukemi Lijadu, Angelique Rosales Salgado, personal communication, May 2025.

Video Viewing Room was initiated with the support of the NYC COVID-19 Response and Impact Fund in The New York Community Trust; annual grants from Lambent Foundation Fund of Tides Foundation and Howard Gilman Foundation; and in part by public funds from New York City Department of Cultural Affairs in partnership with the City Council and New York State Council on the Arts with the support of Governor Andrew Cuomo and the New York State Legislature.