Credits:

Elizabeth Wiet, 2019-20 Curatorial Fellow

March 26, 2020

Muyassar Kurdi is an interdisciplinary artist who works across film, movement, sound, and performance. Her record Voice Games, recorded in collaboration with Ka Baird, was released on Astral Spirits on February 28. This spring, The Kitchen has been working with Muyassar to develop a workshop for MoMA PS1’s Come Together (Apart) festival, which streamed on Vimeo on March 28. To introduce Kurdi’s practice to our audiences, Curatorial Fellow Elizabeth Wiet interviewed the artist, asking her to expand upon her interdisciplinary background, her current projects, and her teaching practice.

You’ve often underscored that you’re a self-taught artist. At the same time, you work capaciously across media: in dance and movement, music and sound art, performance, and film and photography. Can you tell me about your background, and about how you’ve come to develop such a wide-ranging, interdisciplinary practice?

I am a self-made artist, and acknowledging this reminds me of where I come from. There is a raw realness about it. I didn’t go to art school or music conservatory. As a young artist, I made something out of nothing, with no guidance or resources available to me—only burning curiosity and imagination. I feel like I truly got to experiment in art, simply because no one was telling me how to do it at all.

I have very early musical memories from my childhood, when I played in a family band with my blonde mother, who was a folk musician of French-Swiss descent. I also sang in church and took piano lessons. I’d improvise at the piano for hours, with my feet dangling from the piano bench and my upper body moving in a circular motion. I was entranced by free sound. My father, on the other hand, is a Palestinian Arab from Jordan. We would drive to Devon Street in Chicago and visit the local Arab stores—parking on the side of the road on summer days to make falafel sandwiches, while drinking cola and listening to Palestinian music on dubbed cassette tapes. We’d also go to the mosque—the bows and prayer calls were a very poetic sight. At family dinners, my aunts, wearing cream-colored hijabs, would speak loudly in Arabic while cooking. The sounds of language imprint on your nervous system, and when I hear Arabic, I feel connected to my roots.

Growing up in a bi-racial home made me feel like I was being pulled in opposing directions, and making art allowed me to move beyond my strict upbringing. When I was sixteen, I bought my first 35mm film camera. Eventually, photography led to filmmaking, then to movement and embodied performance.

Being part of the underground scene in Chicago also heavily influenced me. Before gentrification, we had many warehouse and underground spaces. I was out every night when I was young, seeing performances that turned my entire world upside down. Though I started off in folk music, the concert spaces I frequented began getting noisier, and things shifted for me, too—I became interested in electronics and jazz, and I began to cultivate a more improvisatory, urgent, and wild performance practice. Though I consider myself a composer, I have no interest in traditional notation. I learned how to read music as a child, but I prefer to play by ear and intuition.

More recently, I’ve started thinking about how art can be a healing practice, and have begun incorporating somatic movements such as Alexander Technique and Feldenkrais into my artistic practice. I am constantly exploring how the disciplines connect. I make dance films because I’m interested in documenting how the body moves in space. But voice was my earliest instrument, and lately I have been creating pieces for electronics and voice. I am interested in how these worlds co-exist: the body and the machine.

Your record Voice Games, created in collaboration with Ka Baird, was released at the end of February by Astral Spirits. Ka has participated in several projects with The Kitchen, and her new work with Max Eilbacher, Vivification Exercises, was slated to premiere at The Kitchen on April 3 (this performance is now postponed in response to COVID-19). How did you first come to work with Ka?

Years ago, I saw Ka perform in Chicago with her band, Spires That in the Sunset Rise. That performance resonated deeply with me. It was very physical, raw, meditative, chaotic, and ritualistic. I was in my early twenties at the time, and still learning how to direct my own energy in performance—I found Ka’s performance inspirational, especially because women were underrepresented in experimental music. Ka and I stayed loosely in touch, and our friendship and interest in each other’s work deepened when I moved to New York City after spending time traveling, performing, and teaching in Europe. We eventually vocalized and recorded together at Pineapple Reality in 2017.

Voice Games is composed of material we recorded at Pineapple Reality and at the Pioneer Works studio during Ka’s Summer 2018 residency. In the recordings, you can hear me laugh. At one point, it felt like we were on one long car ride, and we were getting silly: “Get out of the car, Ka!” We were really listening to each other. It felt like we were old friends.

You’ve had quite a busy year: in addition to the release of your new record with Ka, you’re also finishing up a commission with Roulette in Brooklyn. Can you tell me more about your current projects?

I was scheduled to be in residency at the Watermill Center with Lucie Vitková and OPERA ensemble this April, though that has been postponed to 2021. In May, I’ll begin a residency at HarvestWorks, working on a piece titled Brain Works, which will be a non-linear, interdisciplinary piece ruminating on embodiment after brain injury. I haven’t directly addressed this experience in my work before, but my rebirth after my injury has heavily informed my life as an artist. Because I have had to re-learn how to walk, talk, speak, and regain my cognition, I have grown incredibly aware of how I exist in my body. I am very happy to be alive—I feel intensely alive.

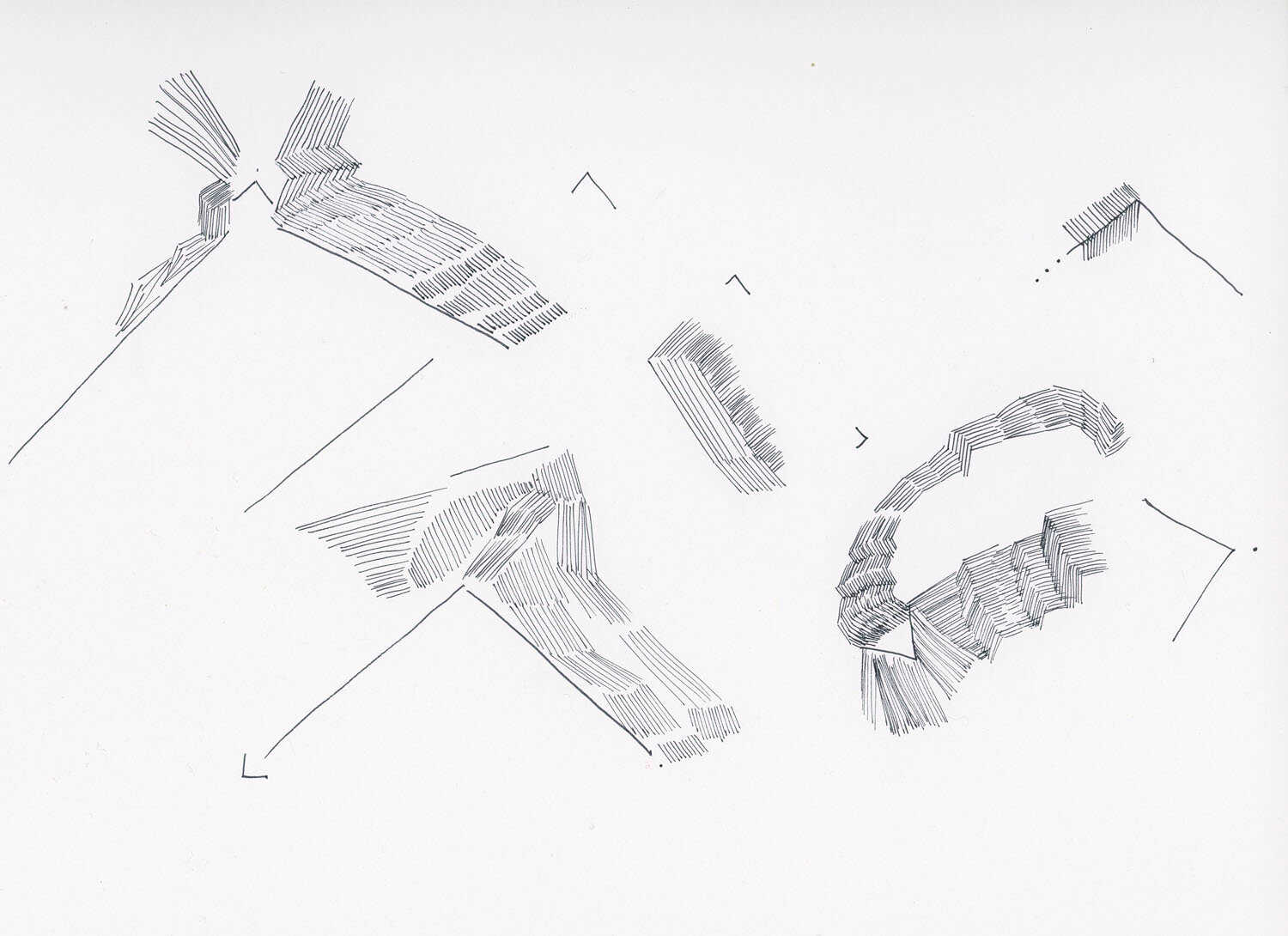

For my current commission at Roulette, I’ve been working on an interdisciplinary piece titled Vast Geographies. The piece will include a short 16mm dance film featuring Eryka Dellenbach followed by a concert with Luke Stewart on bass and me on electronics, bells, and voice. This work is centered on ecology, movement in stillness, cycles, and ritual—we’ll perform amidst many scattered graphic scores and earthly materials. Over the summer, I’ll also be shooting a new 16mm film titled ألوان (colors) with the dancer Miriam Parker. This piece will be a sonic meditation on light and color while exploring the theme of ancestry—an homage to my Palestinian roots.

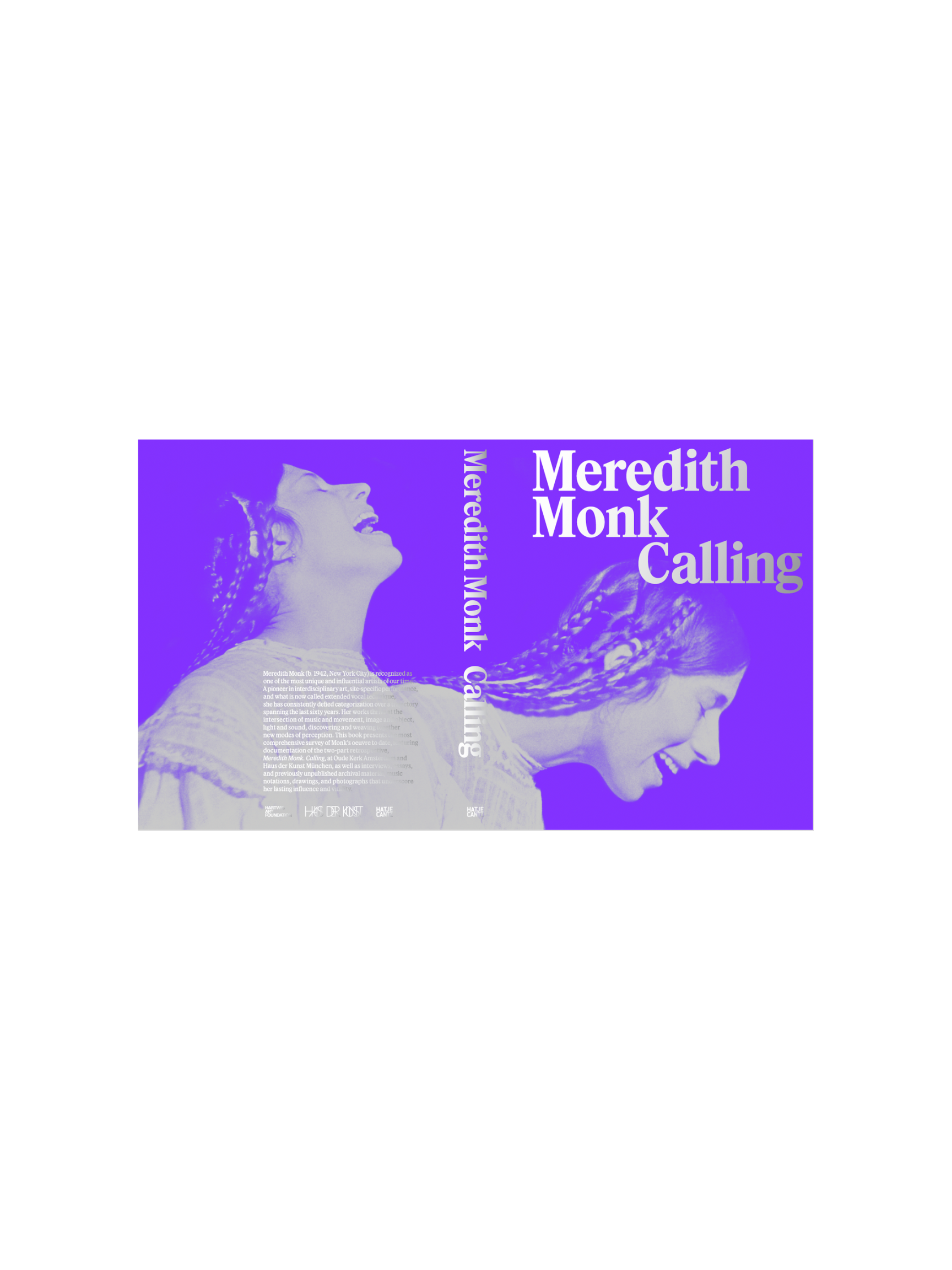

I want to take a step backward and talk with you about genealogies and performance history. One of the first things you did when you came to New York was enroll in one of Meredith Monk’s workshops—and I know that your work with Monk is foundational to your current practice. Critics have also compared your vocalization style to Diamanda Galás (who, like Monk, has presented several projects at The Kitchen). In reviewing your single “I’m Not Really Here I’m Just Going Through the Motions” for Tiny Mixtapes in 2014, Maxwell Allison wrote, “Kurdi’s voice escapes in a theatrical bellow that evokes Diamanda Galás’s plague mass invocations as it floats over the din in clear and ringing tones.” I absolutely love that quote—it’s so striking.

Are there other artists from previous generations with whom you consider your work to be in dialogue? For instance, I can’t help but wonder whether the title of your film Field Dances is a reference to Merce Cunningham.

While I was still living in Chicago, I traveled to New York to take my first Meredith Monk workshop at her loft on West Broadway. I remember arriving early and having breakfast with her in her kitchen while we casually talked—I was a bit stunned by it all. At the time I was already working with many modalities, but this experience helped me to understand further the connection between the body, voice, sound, deep-listening, and film. Through the workshops I met Janis Brenner, from whom I’ve since taken voice lessons and whose dancing I recently shot on 35mm film in Central Park and at the Kaufman Studio at Juilliard. As far as Field Dances goes, the title wasn't a reference to Merce Cunningham, but I did learn after the fact that he had a piece with the same name—and, of course, I love his work.

New York has changed rapidly, but there are still bits of “old” New York that make it worthwhile. I enjoy collaborating intergenerationally because it brings this “lineage” to life—it makes me feel like I am a part of something bigger. One year after I moved to New York, I met the musician Daniel Carter, and we’ve been collaborators ever since. He’ll come over to my apartment in Queens and I’ll feed him a home-cooked meal while we talk and play music—sometimes talking more than playing. I later met poet Steve Dalachinsky and his wife Yuko Otomo at Anthology Film Archives, during a screening of some obscure Japanese film. When we got to talking, I found out they had also worked with Daniel. Steve represented old New York to me, and before he died, we would go to each other’s performances. He’d ask me, “Mu, why are you always laughing at my poems?”

At Anthology Film Archives I also met Bradley Eros, and I later collaborated with him in both performance and film. He constantly blows my mind with his encyclopedic knowledge of art. I have always had a love/hate relationship with words: I’m fascinated by linguistics, and I love poetry, but words often feel entrapping. At times, I feel like a fraud when I use words. But Bradley reminds me to bend words and make love with words.

More than many artists, Monk considers her role as a teacher—as a workshop leader—to be central to her practice. Like Monk, you’ve developed a robust workshop practice of your own. Can you tell me more about what these workshops are like, and about how to understand the relationship between your work as a teacher and your work as an artist?

Teaching is always such a privilege. I often feel inspired by my students, who open up new worlds to me, and to each other. This past year, I taught a workshop at Bilgi University in Istanbul, Turkey, to a large class of young women from the university’s dance and music department. What beauty and openness!

Because I work with embodied sound as an artist, many of my workshops include various exercises in voice, movement, and performance. In a workshop setting, it’s crucial to toss the ego aside and to truly explore an unknown part of yourself. It is a time of hard work, empowerment, deep listening, and inspiration. A gathering like this also acts as a protest, because it allows us to become embodied and to feel connected with others.

My work as an artist is woven throughout my teaching—it’s a fluid connection.

Your workshops incorporate many different actions and disciplines: sound, movement, and even text and spoken word. I know they demand quite a lot of the participants. But at the same time, you also stress that your workshops are open to all—that anyone, regardless of background, can participate. Where does this desire to create an open, generous space for your workshop participants come from?

My idea of an ideal space is one that is safe, judgement-free, and expansive. I want to create space for every unique body, and I don’t want to tell that body how to exist, or what is right or wrong. I open up my workshops to anyone, regardless of discipline or previous training, because I don’t find the latter necessary to fully access imagination. I want to remain sensitive to accessibility and inclusivity, and I hope to highlight the uniqueness of each body while creating a multi-sensory experience.