Credits:

By Kamikaze Jones, Artist

June 27, 2023

“Don’t Look to Diamanda Galás for Comfort” (1) reads a New York Times headline preemptively covering the premiere of Galás’s “electro-acoustic monodrama” (2) InSEkta, which opened the Serious Fun! Festival at Lincoln Center on July 8, 1993.

Comfort, or lack thereof, seems to be a perpetually divisive notion in the critical analysis of Galás’s oeuvre. For generations, many have taken deep solace in her virtuosic vocal technique, with its seemingly boundless array of colors and shapes, fathomless shadows and serrated edges—all of which coalesce into extreme protestations of unfettered rage and universal mourning. Galás buttresses her classically trained yet intentionally abject vocalizations with singular compositions: tectonic upheavals of piano rooted in the Satanic folklore of the blues, or piercing electronics that evoke Karlheinz Stockhausen drowning in the river Styx. For the uninitiated square or shrinking violet, these guttural expulsions are often mislabeled as surface-level provocation, full of sound and fury and signifying nothing. Yet underneath the deathly exterior—the dense clusters of scar tissue and exposed nerve endings that characterize her catalog—there has always been a life-affirming pulse.

Galás wrote, composed, and performed InSEkta as a work-in-progress on the second-floor performance space of The Kitchen between June 24 and 29, 1993. This engagement represented Galás’s participation as The Kitchen’s inaugural Artist-In-Residence in a residency program likened to “a kind of contemporary patronage” (3) by the Executive Director at the time, Lauren Amazeen. Galás created InSEkta one year after her widely known performance Vena Cava (1992), which was also presented at The Kitchen. Vena Cava was a solo piece that ran from February 19 to March 8, 1992 and was subsequently released as a live album the following year after garnering vast critical acclaim. A propulsive yet minimalist elegy dedicated to her brother, the playwright Philip-Dimitri Galás, who passed away from AIDS in 1986, Vena Cava paid homage to the dramaturgic trademarks of Philip-Dimitri’s “avant-vaudeville” style of performance, characterized by rapid-fire delivery and contrapuntal vocality, with Diamanda appearing somewhat anomalously in a vestal white mini-dress. Marking a shift from the hyper-interiority and intimate grief of Vena Cava while mining similar themes of isolation and trauma-induced psychosis, InSEkta emphasized systemic issues of mass depersonalization over subjective despair. InSEkta revolved around a kinetic and purposefully overwhelming set piece in which Galás was loosely encased for the majority of the performance: a twenty-foot-long, six-foot-high, motorized chain-link cage suspended mid-air over a field of glittering barbed wire, jostled and manipulated by a series of winches and affixed with various stroboscopic lights, ring modulators, and concealed microphones.

In her essay “On Concert Theater,” InSEkta director Valeria Vasilevski wrote that “during the course of the piece her [Galás’s] voice shook the cage and her body started the cage swinging and tilting and shimmering to the modulations of her musical ascents. Because the cage was motorized, we could tilt it to form extremely steep slopes which she had to climb, hanging from chain link.” (4) The artist deployed this volatile mise en scène to amplify the parameters of both institutionalized and psychospatial entrapment, creating an abstract taxonomy of helplessness—one that alluded to imagery of frenzied lab rats, diassociated rape victims, and faceless casualties of biological warfare, each clambering to escape captivity. The references to state-mandated expendability and perceived insignificance were echoed in the sound design, at times reminiscent of the dipterous chittering of unseen vermin. To allow for Galás’s physical mobility to remain unimpeded from within the cage, her naked chest was fitted with “a double gun holster made of leather,” to which two personal wireless microphones were attached, further reinforcing the insectile aesthetic. (5) In a recent conversation, InSEkta lighting designer Dan Kotlowitz, who had worked with Galás previously on Vena Cava as well as Plague Mass (1990), claimed that Galás originally wanted to introduce live insects into the piece by unleashing a thousand cockroaches onto the deck during her performance—a request that was ultimately vetoed, being considered unviable for Lincoln Center’s Alice Tully Hall. (6)

It is somewhat ironic yet strangely fitting that such a mechanically exuberant spectacle has little tangible presence in the archive: no video documentation of InSEkta was readily available upon investigations in The Kitchen and Lincoln Center’s archives at the time of this publication. Furthermore, the critical reception I was able to locate in addition to the previously mentioned New York Times preview consists solely of two arrogant and dismissive writeups that, in this fledgling archivist’s humble opinion, say more about the thinly veiled misogyny rampant in the mainstream music journalism of the era than they do about the work. Stymied by the stagnancy of the Western classical canon, Peter G. Davis of New York Magazine referred to the piece as “InSEkta Repellent” and claimed that “deprived of Con Edison’s assistance, Diamanda Galás’s InSEKta would instantly vaporize.” (7) Edward Rothstein of the New York Times compared it (pejoratively) to “one of those old haunted-house rides in amusement parks." (8)Perhaps it was this bout of negative press that later spurred Galás to write “Critical Knowledge: The Education of a Music Critic”—a short transgressive screed at the end of her collected writings The Shit of God (1996), in which she sodomizes an unnamed male journalist before urinating in his mouth, reducing him to a blubbering heap until he can only mutter “Diamanda is a great genius: when may I kiss her ass?” (9)

Interestingly enough, both reviews cite the seemingly unperturbed reaction of the audience as indications of the performance’s failure. Davis asserts that “when the lights went up, I saw only cheery theatergoers who had apparently experienced nothing more disturbing than a titillating freak show.” (10) Rothstein echoes this dubious sentiment by stating “when the audience left, the friendly banter and loud conversation one heard were not evidence of a wrenching theatrical experience.” (11) That both these men anticipated a shellshocked, catatonic crowd as an accurate barometer of emotional impact was a dated notion even then. When speaking to Stephen Rueff, former production manager at The Kitchen, Rueff insisted that “Diamanda’s lightness and joy behind the scenes was every bit as memorable as her passion and fury onstage.” (12) I would venture to say that the subsequent buoyancy of the crowd deserves a contemporary reappraisal. In lieu of the lazy rhetoric espoused by Davis and Rothstein that amounts to “I don’t know why the caged raven shrieks”—a haughty shrug that positions the confined diva as a hapless practitioner of opaque histrionics—the audience reaction to InSEkta could be reassessed as signs of a community galvanized rather than proof of a clump of flippant and unaffected bystanders.

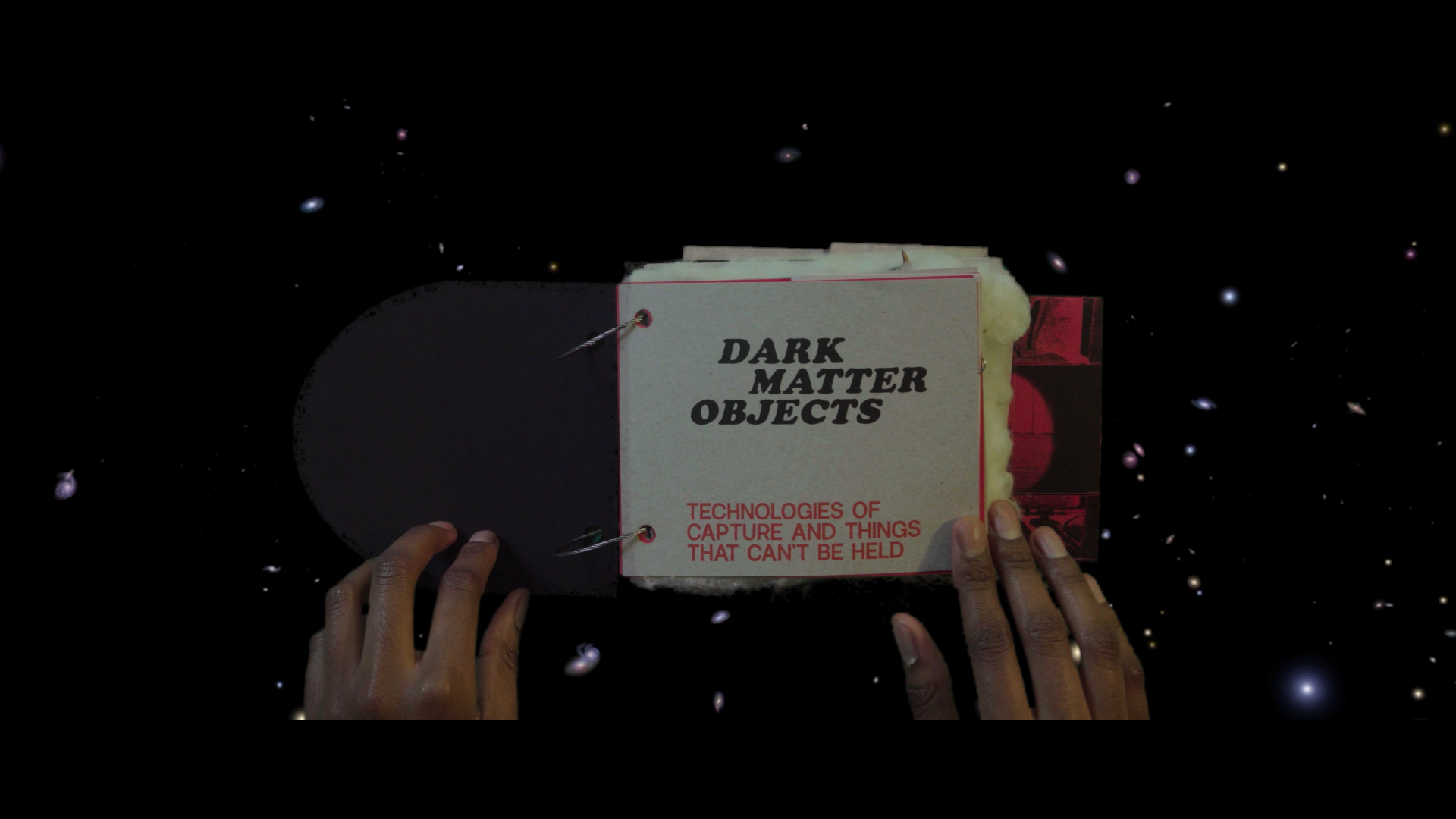

During our conversations, both Kotlowitz and Rueff agreed that the sheer immensity of the production made touring InSEkta virtually impossible. It also never received a formal audio release, further limiting the work’s transmission after its premiere. Now, thirty years after its debut, InSEkta remains an underexamined facet of Galás’s staggering body of work. Incidentally, InSEkta’s lack of archival materiality echoes its thematic focus on anonymous populations and weaponized erasure.

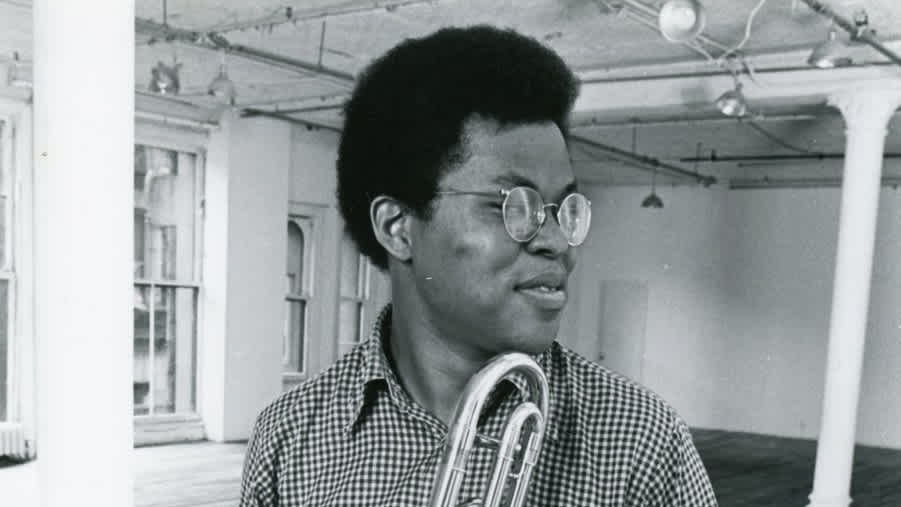

The Kitchen’s initial support of the piece through its residency program stands as a testament to the institution’s longstanding legacy of cultivating a platform for uncompromising artists working in experimental voice. In the ensuing decades, InSEkta has not diminished in its generative voltage. A range of artists’ practices at The Kitchen—from the gothic cathedrals and haunted plantations conjured by spiritual protege M. Lamar, to the diasporic deconstructions of Muyassar Kurdi, and the rhapsodical demonology of Holland Andrews—continue to extend Galas’s electrifying paradigm.

BIO

Kamikaze Jones is an interdisciplinary artist whose work explores extended vocal technique, queer hauntologies, and ritualized erotic transcendence. He is the arts editor of WUSSY Magazine.

FOOTNOTES

- William Harris, “Don’t Look to Diamanda Galás for Comfort,” The New York Times, July 4, 1993. To see the full article, click here.

- Press release for Diamanda Galás, INSEKTA at The Kitchen, June 24–29, 2023. To see the full press release, click here.

- Ibid.

- Valeria Vasilevski, “On Concert Theater: A Director’s Notes: Pioneering a New Form or Putting a Dress on a Tree?” Theater 30, no. 2 (2000): 75–81. https://doi.org/10.1215/01610775-30-2-75.

- Ibid.

- Dan Kotlowitz in conversation with the author, March 24, 2023.

- Peter G. Davis, “Watts and Megawatts,” New York Magazine 26, no. 29, July 26, 1993.

- Edward Rothstein, “A Diva Makes a Cage Her Vehicle,” The New York Times, July 10, 1993.

- Diamánda Galás, The Shit of God (New York: High Risk, 1996).

- Davis, “Watts and Megawatts.”

- Rothstein, “A Diva Makes a Cage Her Vehicle.”

- Stephen Rueff in conversation with the author, March 24, 2023.