Credits:

By: Amari-Grey

June 25, 2025

Scene 1: Into the Archive

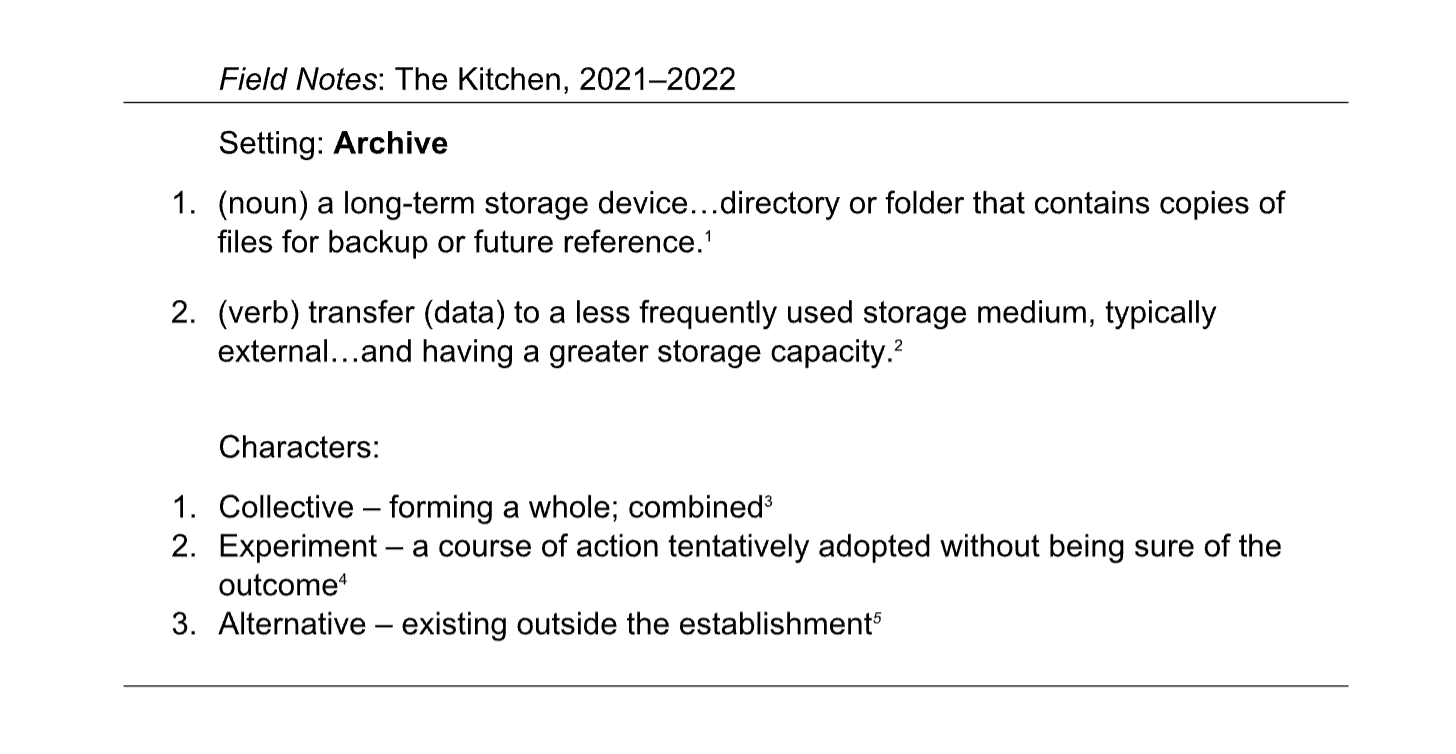

In 1971, on the western end of Broadway Central Hotel at 240 Mercer Street, the Mercer Arts Center emerged as “a family of theaters under one roof that, until very recently [in 1971], leaked.” At Mercer, Steina and Woody Vasulka—early pioneers of video art and New Yorkers of six years at the time—rented the hotel’s 30-foot-wide disused kitchen “and equipped it with videotape machines, tape recorders, television monitors, loud speakers, a piano, and other equipment.” (7)

Conceived as a site for showing the then-nascent medium of video, this small, mutable space was capable of shifting between production, presentation, and performance for those who knew it was there, or who trickled in from one of the Center’s five other theaters. What became “The Kitchen” arose here as a collective of artists and directors, intentionally unstructured and nonhierarchical, “donating their time” to a medium based in that very material.(8) This experiment in giving time freely, and offering space for it to be spent, stood out against the still relatively limited access to video technology and paucity of time in an art world conditioned by capitalism.

Coming out of the 1960s, where similar downtown experimental arts spaces, like the East Village’s Electric Circus, were “short-lived,” (9) the opening of The Kitchen in June 1971 (10) regathered artists with experimental intentions, encouraging the developing field to survive the unsteady fiscal climate. Centered on providing access to the increasingly public medium of video, The Kitchen operated on charitable donations (11) and an admissions split with presenting artists (12), holding weekly music performances and a Wednesday “Open House” where anyone in attendance could screen their videotapes. In its early years, The Kitchen was housed as a project under the fiscal sponsorship of Howard Wise’s nonprofit Electronic Arts Intermix (EAI), enabling the collective to receive New York State Council on the Arts funding while remaining unincorporated as a nonprofit institution. In this way, with a lack of formalization and growing support from artists and art workers across experimental disciplines, The Kitchen diverged from both the city’s commercial gallery scene and established institutions, aiding Mercer Arts Center in becoming what the New York Times dubbed “a kind of downtown Lincoln Center seen through the wrong end of a telescope.” (13)

A reputation for inverting norms would follow The Kitchen’s evolution as the Vasulkas departed in 1973, leaving both New York and the collective, and Robert Stearns became the space’s first Executive Director. With an expanding calendar of screenings and the incorporation of live music programming, The Kitchen’s audience was widening beyond the 150-person capacity at the Mercer Arts Center. Two years after the beginnings of the experiment, The Kitchen faced a rising budget and impending rent increase at the Center, cementing the decision not only to leave Mercer’s kitchen in June 1973, but to separate from EAI and become an independently incorporated nonprofit organization.

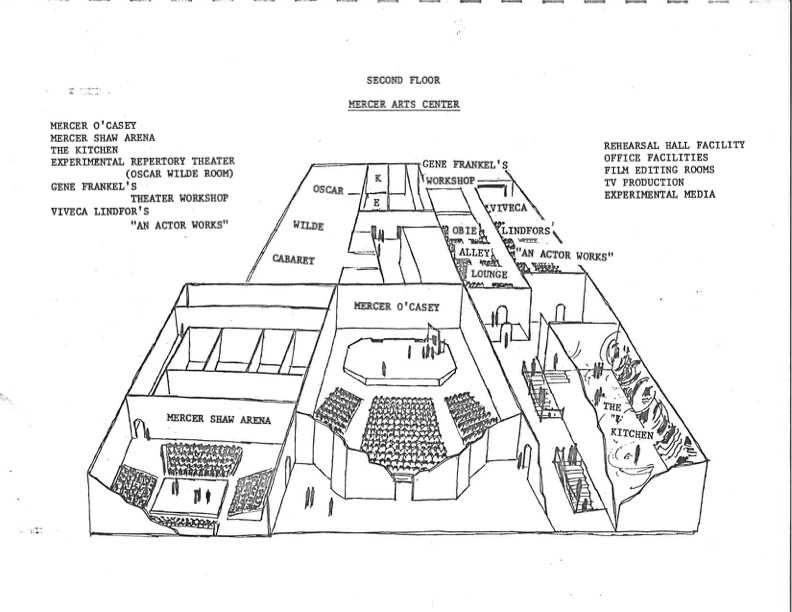

Working with volunteer lawyers, The Kitchen incorporated as Haleakala Inc.—taking on a name that means “house of the sun”—as Stearns formalized the organizational structure, integrating a board of directors and advisors, including art dealer Paula Cooper and artists such as Caroline Stone and Philip Glass. That fall, an agreement with the landlord of 484 Broome Street on the corner of Wooster Street), the former LoGuidice Gallery Building, allowed the organization to lease the second floor for $10,000/year, providing space for performances, a gallery, and a video viewing room. (14)

Moving further downtown into the still burgeoning SoHo district, The Kitchen continued to situate itself both physically and artistically “on the fringes” of “the dominant art-world centers.”(15) In the 1975 Kitchen Yearbook publication, Stearns named the institution’s intentions:

The Kitchen chooses to present artists’ current works which are sometimes unpolished sketches and ideas and at other times highly professional accomplished works. This flexibility is often impossible for larger, more established institutions to attempt. It has become vital that, as the nature of contemporary art activity shifts that a means be kept open for the artist to reach a public. If the older institutions cannot do this, it is necessary to invent new ones. If the older institutions cannot do this, it is necessary to invent new ones. One of the significant evolutions in the art world in the 1970 s has been the development of what are sometimes called “alternative spaces.” The term has some meaning. However, it carries with it a connotation of tentativeness, yet also betrays a comparison to some other form of institution— perhaps the museum. The Kitchen is not alternative to anything. It has been invented for the contemporary art idiom: intensely personal, uncollectable art work and activity. The Kitchen’s structure and its staff are uniquely suited to handle the special and changing requirements.

Confronting the relationality inherent in being designated (or not designated) “alternative,” Stearns seems to ask if it is possible for the now-institution to assert itself still as an experiment, independent and “uncollectable,” rather than an alternative option to the mainstream. These questions resonated for others at the time, such as critic John Rockwell, who likewise wondered at The Kitchen’s transformations, writing in 1977, “The Kitchen epitomizes what is best about the extraordinary artistic community that thrives in the midst of our biggest city. Yet at the same time, it is itself an ‘edifice,’ in that it’s larger and more firmly established than the alternative loft spaces that otherwise house this sort of work. If that’s a paradox, it’s a productive one.” (16) Such comments represent the trajectory of The Kitchen’s first half-decade of existence, during which engagement from the artistic community and increasing attention to new media art pushed the original collective towards what Steina Vasulka called “the dilemma of success,” (17) where the need for a larger space and the opportunity for governmental funding could outweigh the spirit and opportunities of alterity that inspired the institution’s formation. We might consider what it means for the institution to have shifted from the intimacy and multimodality of a bygone kitchen in a former hotel to the enshrinement of the experiment in a more visible, long-term site; from the self-governance of artists working with a medium still considered radical and illegitimate towards the legal conditions of nonprofit status and proximity to, or intimacy with, the mainstream.

Scene 2: In Support; Building As Site

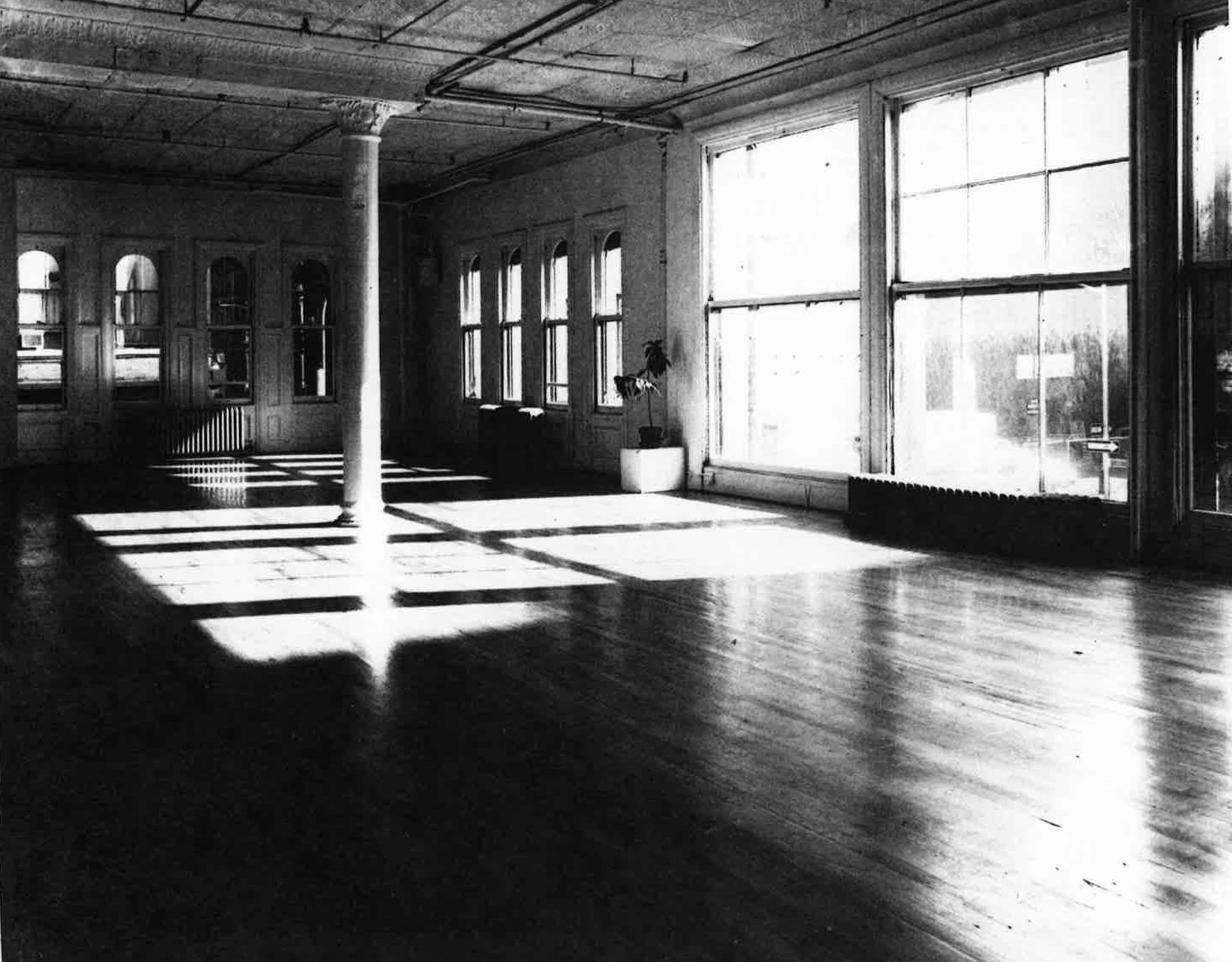

November 18, 2021. Early on that Thursday night, I slipped into the opening of In Support— a six-floor exhibition marking the end of The Kitchen’s fall season at its home on West 19th St.

The institution relocated to Chelsea from 484 Broome Street in 1986, renting an ice storage facility turned artist studio from Dia Art Foundation and then purchasing the building the following year. With this move, the decade-old institution found itself at the helm of experimental arts in a neighborhood removed from the now-established arts center of SoHo, and it began laying the groundwork for the area to become “the gallery hub [Chelsea] is today.” (18)

Scanning the room, I listened through the murmuring visitors into the walls of the former warehouse, hearing echoing footsteps, the chime of the elevator. Featuring Fia Backström, Francisca Benítez, Papo Colo, and Clynton Lowry, and organized by curator Alison Burstein, In Support investigated the relationship an institution has with its people, whether patrons, artists, or others:

The title of the exhibition alludes to a stance that institutions commonly articulate in language describing their aims, activities, and ways of engaging publics—for instance when stating that their programming serves “in support” of artistic experimentation. In Support invites participating artists to probe the meaning and implications of such expressions, asking: who and/or what do institutions like The Kitchen support? Who and/ or what supports them? In what ways do institutions position themselves in support of people, projects, or causes? What hierarchies of support exist within and among institutions? Is support inherently good? (19)

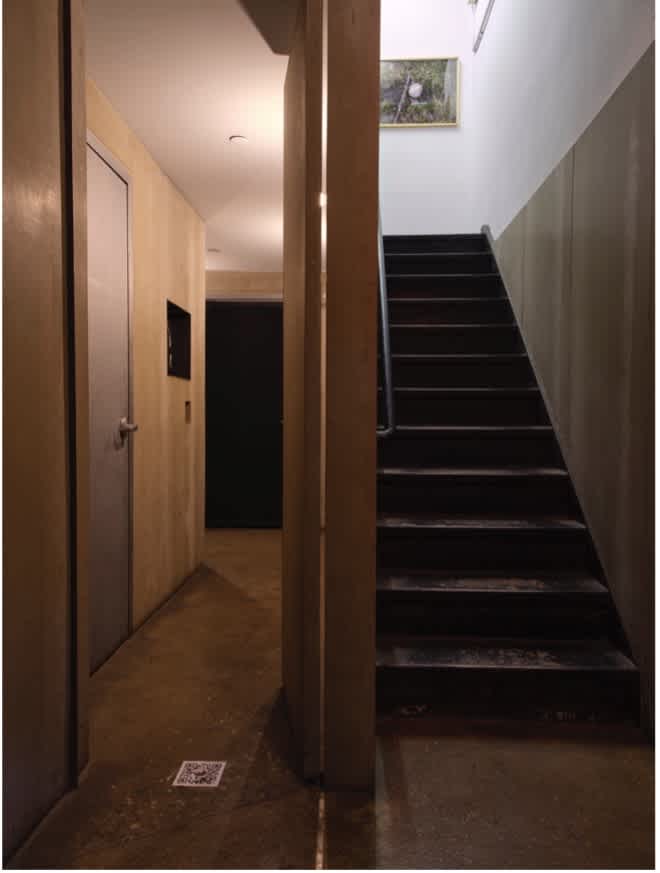

My gaze fell to the ground in front of the lift, where QR codes were planted. Clynton Lowry’s series “Invisible Art Handler” included six such codes on the building’s floors, linked to videos depicting “the typically unseen labor of art handlers.” (20)

The videos show typical maintenance activities taking place, with the person themself rendered invisible through digital editing. Objects of labor seem to be moving on their own—a mop cleaning a floor, a ladder carrying itself between floors of the building, and a saw chopping wood. Calling attention to these often unseen activities, the videos reveal the time, support, and attention that anticipate and follow our visits to the space. As data is processed between the codes and the visitors’ devices, these portions of Lowry’s series sharpen the visitor’s attention to the energy that powers both the operation of the QR codes and their connection and the institution in which they’re housed. These codes resituate our visit to The Kitchen as part of a process rather than a moment, connecting our presence to that of others we may not encounter otherwise.

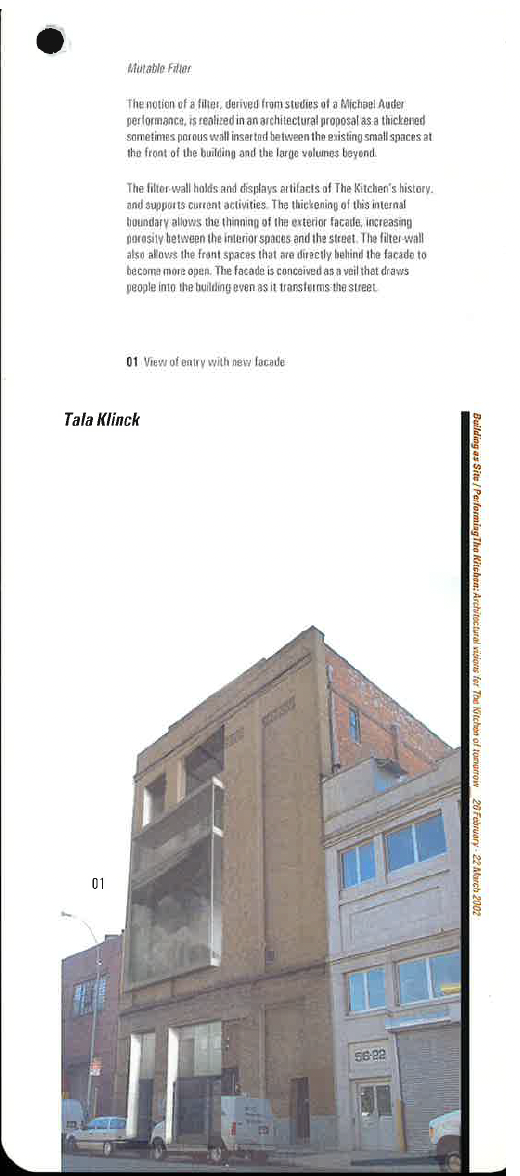

In February 2002, The Kitchen collaborated with Professor Linda Pollak and Harvard Graduate School of Design students to stage an exhibition conducting “an investigation of time and space that challenges preconceived ideas about theater, institution and the city.” (21) Building As Site: Performing The Kitchen read the institution’s location and physicality in a bodily grammar, characterizing the building as both a complex ecosystem and its own lifeform; similarly, the exhibition’s projects considered the interactions and support between “performers, audiences, and the neighborhood” of The Kitchen. (22) Designs by Tala Klinck, then-student and architect, proposed renovations to the edifice featuring a “mutable filter”— “a thickened sometimes porous wall… allow[ing] the thinning of the exterior façade, increasing porosity between the interior spaces and the street.” (23) Rather than “thresholds that divide one space from another,”(24) permeable layers of The Kitchen would “[draw] people into the building even as [they transform] the street.” (25)

Her models attend to the transfer of energy and attention that occurs through the facade of the building, and by increasing the walls’ porosity, she transforms the exchange between The Kitchen and its people from the accident of a leaking roof to an intentional design. As in “Invisible Art Handler,” Klink reveals both person and building as containers and conductors of energy that in their connection blur the notion of site between the physical structure and the network of those powering its operation. Whereas Lowry’s QR codes suggest the residue of human labor that remains in a space, available to be scanned and revived for those attentive to it, Klink’s work recognizes people as activators of The Kitchen before and after entering its site.

Scene 3: Where there’s love overflowing

May 2022. A series of rehearsals marks the rhythm of The Kitchen’s final exhibition in its Chelsea building, before closing for renovations. Organized by Lumi Tan, Senior Curator, and Sienna Fekete, Curatorial Fellow, E. Jane: Where there’s love overflowing ran from April 1 to May 14, 2022, culminating in a performance by the artist’s persona, MHYSA. In the weeks before, the exhibition invited audiences “to listen in on” rehearsals through the closed doors of the first-floor black box. The invitation to eavesdrop on MHYSA’s voice but not her body moderated the audience's access to the diva while emphasizing the labor of the performer and the anticipation for it. Likewise, the elements of the exhibition—digital drawings, gouache text on the walls, sculpture, video, and a diva’s stage—are characterized in the Exhibition Score as performers in units of quintets, trio, and soloist. The exhibition’s title cites a lyric from the song “Home,” a classic from The Wiz, written by Charlie Smalls and first sung by Stephanie Mills as Dorothy in the 1975 Broadway premiere. Performer “group two,” a quintet of gouache paintings hand-brushed onto the walls, chronicles the timeline of the song’s renditions, “start[ing] when Stephanie Mills first breathed life into it, and end[ing] with Jazmine Sullivan, the R&B queen of our contemporary time.” Assembling a history not only of the song’s performance but of Black popular music as a loving body, E. Jane positions the exhibition as “talking about the archive as a space to find love overflowing.”

Performer four, the stage, transforms with MHYSA’s presence into a site where energy flows between her body, the structure, and the floor. Reading the surface as an extension of Klinck’s “mutable filter", this to become stored in The Kitchen’s site, just as the performer summons up “the reverberations” (28) already archived in the grounds. “Where there’s love overflowing” then serves as a directive, summoning the most loving of “the residues of [The Kitchen’s] many histories” (29) to flow into audiences today. This intention to call upon love, shared histories, and presence concluded this era of the institution’s physical space, offering a throughline for its ongoing and future evolutions.

Since 2022, The Kitchen has taken up residence at Westbeth Artists Housing while the Chelsea building undergoes renovation, in a loft space that visually and affectively channels the spirit of the former Wooster Street loft. As “a version of a space that the Kitchen has grown beyond,” the temporary location represents what Executive Director Legacy Russell called “a chance to revel in our history, to champion those who brought us to this point and to bring in new voices and perspectives, too.” (30) In this setting, the organization holds a heightened proximity to the beginnings of its experiment and the questions of its originating collective, as this period “without walls” makes space for new considerations, energies, and love to overflow.

Footnotes

- Dictionary.com,“archive,” accessed May 19, 2025, https://www.dictionary.com/browse/archive.

- Oxford Languages, (Oxford University Press, 2023), under “a rchive.”

- Dictionary.com, “collective,” accessed May 19, 2025, https://www.dictionary.com/browse/collective.

- Oxford Languages, “experiment.”

- Dictionary.com, “alternative,” accessed May 19, 2025, https://www.dictionary.com/browse/alternative.

- McCandlish Phillips, “Mercer Stages Are a Supermarket,” New York Times, November 2, 1971, https://www.nytimes.com/1971/11/02/archives/mercer-stages-are-a-supermarket.html.

- Tom Johnson, “Someone’s in The Kitchen — With Music,” New York Times, October 8, 1972, https://www.nytimes.com/1972/10/08/archives/someones-in-the-kitchen-with-music.html.

- Johnson, “Someone’s in The Kitchen.”

- Nick Hallett, “Visual Music at the Mercer Street Kitchen (1971–1973),” The Kitchen On Mind, May 27, 2021, https://thekitchen.org/on-mind/visual-music-at-the-mercer-street-kitchen-1971-1973.

- Woody Vasulka, Steina Vasulka, Don Foresta, and Christiane Carlut. “A Conversation, Paris, Saturday 5, December 1992.” Vasulka.org., accessed September 3, 2024, https://vasulka.org/Kitchen/essays_carlut/K_CarlutConversation_01.html.

- Robert Stearns, “The Kitchen,” Electronic Arts Intermix, May 2001, https://www.eai.org/user_files/supporting_documents/Bob_Stearns_Kitchen.pdf

- Leendert Drukker, “The Kitchen: Creative TV’s Concert Hall,” Popular Photography, May 1974.

- Phillips, “Mercer Stages Are a Supermarket.”

- Stearns, “The Kitchen.”

- Gwen Allen, “In on the Ground Floor: Avalanche and the Soho Art Scene, 1970–1976,” Artforum, November 2005, https://www.artforum.com/print/200509/in-on-the-ground-floor-avalanche-and- the-soho-art-scene-1970-1976-9737.

- John Rockwell, “Something’s Always Cooking in The Kitchen,” New York Times, April 29, 1977, https://www.nytimes.com/1977/04/29/archives/somethings-always-cooking-in-the-kitchen.html.

- Jud Yalkut, Woody Vasulka, Steina Vasulka, Shridhar Bapat, and Dimitri Devyatkin, “Open Circuits: The New Video Abstractionists,” Vasulka.org, https://vasulka.org/Kitchen/essays_yalkud/K_Yalkut.html.

- Sara O’Brien, “The Kitchen in Chelsea.” The Kitchen On Mind, March 20, 2018. https://thekitchen.org/on-mind/the-kitchen-in-chelsea/.

- Alison Burstein, “Introduction,” in exhibition booklet for In Support, The Kitchen, 2022. Published in conjunction with the exhibition In Support, organized by Alison Burstein, Curator of Media and Engagement, with project management by Zack Tinkelman, Production Manager, at The Kitchen, November 18–March 12, 2022. https://assets.ctfassets.net/a9iaiu8vcml1/2BF3RENUGoDG4NnrpS2RAt/933ee8b1df15b768bb2daef76a2c07ad/InSupport_2022_March_Digital.pdf.

- Burstein, “Introduction.”

- The Kitchen, press release for Building As Site: Performing The Kitchen, February 26–March 22, 2002.

- The Kitchen, press release for Building As Site.

- The Kitchen, Building As Site Exhibition Guide, The Kitchen, 2002. Published in conjunction with the exhibition Building As Site: Performing The Kitchen, organized by Linda Pollak and presented at The Kitchen, February 26–March 22, 2002.

- Andrea Ling, “The Girl in the Wood Frock,” Master’s thesis, University of Waterloo, 2007, https://uwspace.uwaterloo.ca/bitstream/handle/10012/3032/The_Girl_in_the_Wood_Frock.pdf.

- The Kitchen, exhibition guide for Building As Site.

- E. Jane, exhibition score for E. Jane: Where there’s love overflowing, The Kitchen, 2022. Published in conjunction with the exhibition E. Jane: Where there’s love overflowing, organized by Lumi Tan, Senior Curator, and Sienna Fekete, Curatorial Fellow, and presented at The Kitchen, April 1–May 14, 2022. http://archive.thekitchen.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/04/EJaneExhibitionScore.pdf

- Alexis Jacquet, “A Dialogue with E. Jane,” edited by Sienna Fekete, The Kitchen On Mind, May 10, 2022, https://thekitchen.org/on-mind/a-dialogue-with-e-jane.

- O’Brien, “The Kitchen in Chelsea.”

- O’Brien, “The Kitchen in Chelsea.”

- Brian Seibert, “The Kitchen Will Spend Some Creative Time in a Westbeth Loft.” New York Times, August 25, 2022, https://www.nytimes.com/2022/08/25/arts/dance/the-kitchen-at-westbeth.html

BIO

Amari-Grey is a writer, curator, and research-based artist. Her practice considers memory, time, and possibility for/through black trans peoples, with herself as a site of study. In the recent essay series Digital Semiotics & Pandemic Intimacy (CJLC), she took the context of quarantine to decipher the libidinal stakes of her self-translation and interaction in cyberspace, exploring the recapitulation(s) of antiblackness from the physical into the digital. Currently she is making new writing and curatorial projects on the function of death and Our origins in the universe.

@amarixgrey