Credits:

By Nick Hallett, musician, artist, curator

May 27, 2021

Visual Music defends a most sublime impossibility—that the eyes may be seduced to hear. The concept has served as a useful analogy for the creation of art since at least the Renaissance, when painter Giuseppe Arcimboldo took a break from eccentric, fruit-bearing portraiture to match the colors of the rainbow with the harmonics plucked on Pythagoras’s Monochord. In 1910, composer Alexander Scriabin scored lighting cues directly into the manuscript of his symphonic poem, Prometheus: Poem of Fire. A few years later, Thomas Wilfred’s mechanical Clavilux illuminations swirled sinewy trails of color across a small, dark screen, predicting the TV set.

Electrical current soothes out the vibratory consciousness of Visual Music, as it transitions one kind of signal into another. In Berlin, during the early 1930s, László Moholy-Nagy and Oskar Fischinger demonstrated this by drawing patterns onto the optical soundtrack of filmstrip, and the inverse, printing the audio waveform onto the image itself. Fischinger’s non-objective animations, set to zestful string symphonies, would result in an invitation to work in Hollywood. On top of allowing him to flee Nazis, this move acknowledged the cultural value of meant-to-be-meaningless abstraction. The opening credits for 1938’s An Optical Poem, for MGM, describe this as “novel scientific experiment…to convey (music’s) mental images in visual form.”

Scriabin’s dream of the musical-visual experience as unfettered, total sensation would evolve in downtown New York during the late 1960s, at short-lived institutions like The Electric Circus, where Tony Martin’s hand-painted slides and films covered every curve of its spandex interior while electronic music percolated from Morton Subotnick’s Buchla modular synthesizer; or at the Fillmore East, where artists-in-residence the Joshua Light Show projected colorful displays of dyed oil in water, which squished and spun to the beat, precisely because a human was manipulating the light source. The tactility of this method gave way to a kind of performance act, whereby artists could improvise with a visible medium to the music in their ears, which on any night might be Miles Davis, Sly and the Family Stone, or The Mothers of Invention. Blocks away, Nam June Paik was hacking into television sets and the first generation of portable video equipment in collaboration with cellist Charlotte Moorman, much as he had destroyed acoustic violins and pianos years earlier. A 1968 Rockefeller grant secured by WGBH in Boston would enable Paik and Shuya Abe to create their first video synthesizer, fulfilling Paik’s prediction that “the cathode ray tube will replace the canvas.” The exact same Voltage Control Oscillators that sounded from the Buchla could now encode video signals with bright colors, and modulate abstract patterns on TV screens in real time. Visual Music’s vibratory consciousness had gone electronic, and a new generation of video artists would come to play.

IT WAS IN THIS TELEVISUAL LANDSCAPE of scrolling horizontal bars that Steina Vasulka and Woody Vasulka, artists and musicians both, lugged several CRT monitors from their Union Square loft to a disused hotel kitchen at the newly renovated Mercer Arts Center, a complex of theaters programmed with off-Broadway shows and live rock, much of it catering to genderqueer audiences. One might catch a performance of Dr. Selavy’s Magic Theatre, a surreal musical comedy by Richard Foreman and composer Stanley Silverman in the O’Casey; then a double bill of The New York Dolls and Jayne County in the Oscar Wilde Room; while the Midnight Opera Company, a psychedelic jazz fusion band led by the Center’s Music Director Michael Tschudin, played in an adjacent lounge.

Mercer Street offered a tuneful setting for the Vasulkas’ vision—a destination for electronic art and video, with the flexibility of a performance venue, distinguishing it from galleries and video collectives. Andy Mannick, a set builder for the Merce Cunningham Company, designed the room with dance in mind. Tschudin lent his Steinway grand. The monitors—abundantly reconfigurable—were connected via matrix to distribute images throughout the space, a shift from the fixed perspective of cinema. Video images could be seen, combined, and altered as quickly as they were caught on camera, like notes in a chord, or instruments in an ensemble. An early invitation to The Kitchen reads, “We will present you sounds and images…made artificially from various frequencies, from sounds, from inaudible pitches and their beats. Accordingly, most of the sounds you hear are products of images processed through sound synthesizer.” The synesthetic origins of The Kitchen are noticeably in the context of downtown theater. But nothing quite like it had ever truly existed—a room full of TV sets, where each night a different audience would assemble and make applause for a medium they could just as easily watch at home. The difference was in the communities it brought together.

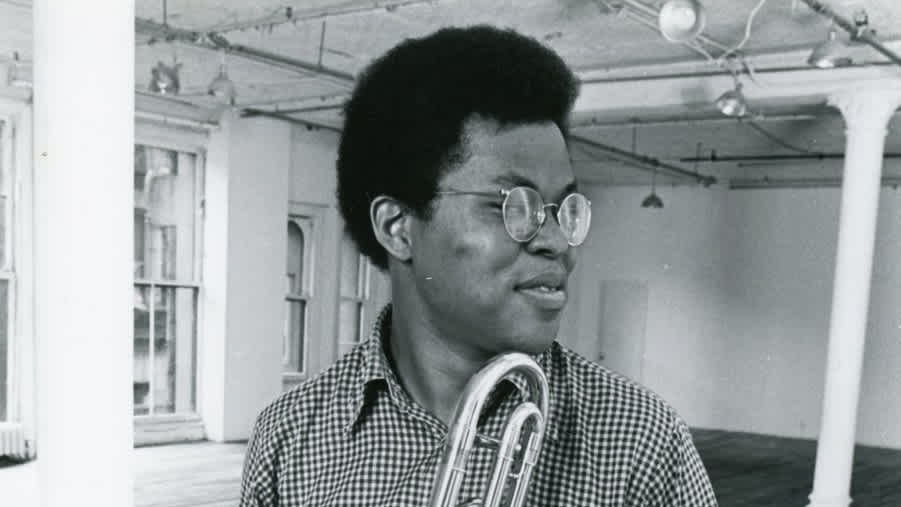

A good example of The Kitchen’s early value system was its Open Screening series, held every Wednesday, which required no invitation to participate. Among the crowd at the very first event were Paik, Jonas Mekas, Shirley Clarke, and a twenty-one-year-old video artist just starting his career, Dimitri Devyaktkin, who showed a “very austere video of performance art” set to the 1968 recording of Robert Ashley’s She Was a Visitor. Hours later, the Vasulkas gave him keys to the theater and the responsibility of organizing its calendar. A team of directors took shape. Far from having purely administrative roles, the “cooks” of The Kitchen also became something of its resident artists. Nineteen-year-old Rhys Chatham had recorded the soundtrack to a set of the Vasulkas’ electronic image pieces. He would program the music series. Shridhar Bapat was hired to navigate the tangled network of monitors, cameras, and playback equipment, and would prove to be just as resourceful as a producer of video festivals. (The term “curator” was gauche.) Dimitri recalls the first seasons as “wide open, allowing anything as long as you talked to Steina early enough, and you got on the calendar. A lot of times we didn’t know what to expect.” The precedent here wasn’t just The Kitchen’s welcoming attitude, but the way an organization could make a realm of technology immediately accessible to artists and activist groups. “The magic of video,” Dimitri reminds us, “was that if you had a great idea, you could realize that idea very easily and quickly. And that was impressive to people. It was the live interaction that we were always interested in, not just simply recorded.”

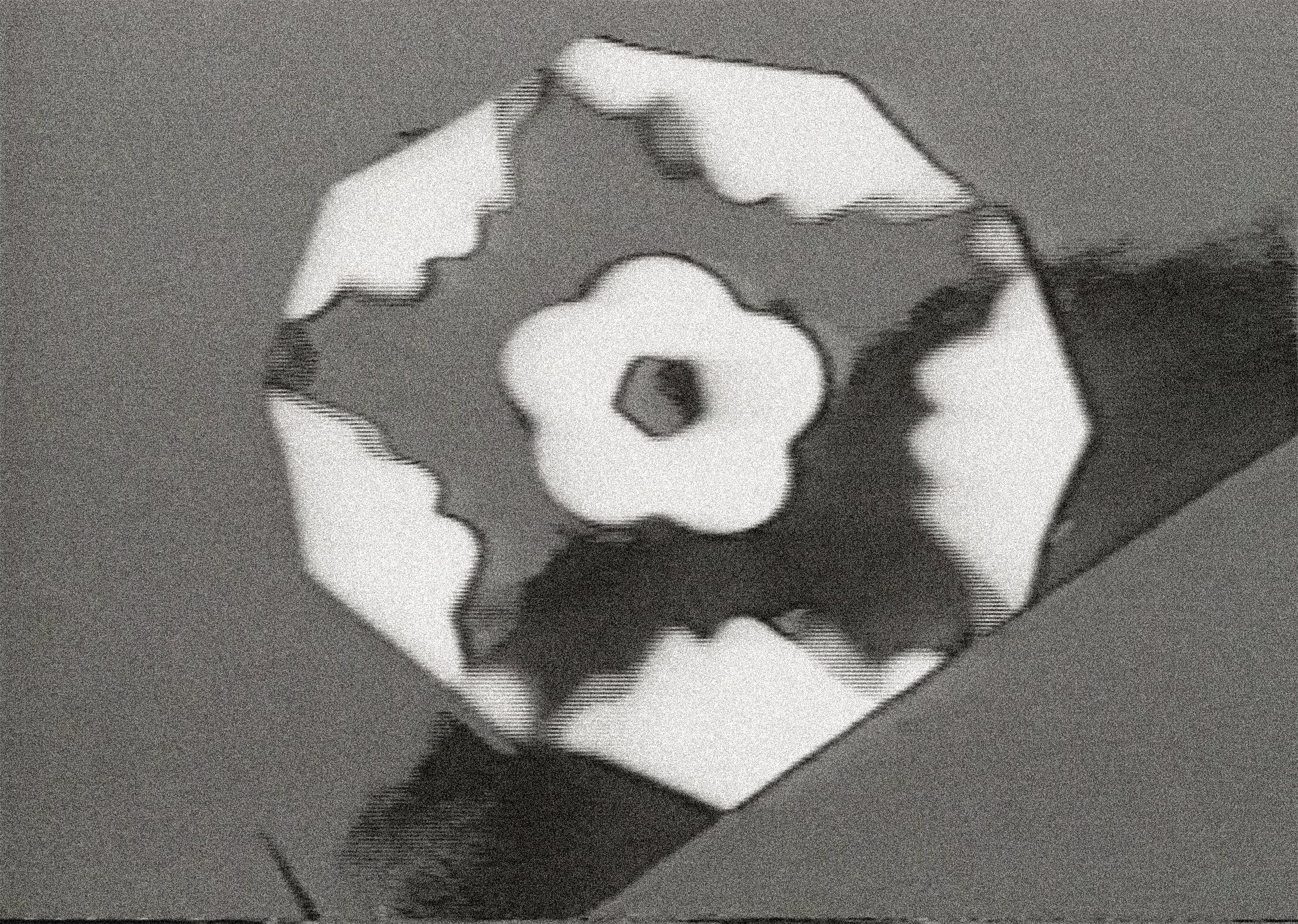

A live interaction could be induced satisfyingly by simply pointing the camera at a monitor of its own image, unfurling a chasm of video feedback. Tilted on its side, the camera would generate trippy mandala patterns that change infinitely, echoing Wilfred’s light sculptures from a half century earlier. Video feedback provides an abstract flow of experience for the eye, like the rumble of electric sound that volleys between microphone and speaker. Too much—of either the visual or sonic—makes volatile noise. But executed by an artist, the effects can be mesmerizing. And Shridhar had earned his reputation as the “best feedback camera turner” in New York. His visualization of Soft Machine’s “A Certain Kind” was shot directly off the monitor in one take. The tape screened at MoMA.

FEEDBACK MANIFESTS IN MODULAR AUDIO SYNTHESIZERS when its components are chained together in a loop. A patch of electronic sound set in motion continues to develop on its own. This cybernetic technique of composition could be explored on the Buchla kept at Subotnick’s Bleecker Street studio, where Rhys was studying when he met the Vasulkas, in a cohort that included Laurie Spiegel, Charlemagne Palestine, and Maryanne Amacher. When it came time to launch The Kitchen’s music series, Rhys briefly entertained asking the band Suicide, favorites at the Mercer Arts Center. The first invitation, however, went to Spiegel. The inaugural concert was held on October 4, 1971, with a performance of her Harmonic Rhythms, an alarm call of throbbing stabs and arpeggiated cries from the Buchla.

Tom Johnson was a music critic for The Village Voice when he paid his first visit to The Kitchen on January 7, 1972 for a concert by Jon Gibson. The program included Voice/Tape Delay, a recorded work that involves phase shifting—another feedback technique—which Johnson described in his review as sounding “like a spirograph drawing.” Johnson was especially struck by the inclusion of live video images by Dimitri, writing, “he somehow managed to superimpose abstract patterns, wave motions, and shots of the musicians in a very effective way.” Johnson would return almost weekly to chronicle the evolving music series, which increased The Kitchen’s visibility as a venue for cutting-edge performance. And while treated as a separate affair from the video program, music would benefit from the presence of televised images. Rhys admits “whenever you gave the Vasulkas or Shridhar or Dimitri half a chance, they would do an instant collaboration with whomever was playing, and the composers would love it.”

The printed program for Rhys’s Music with Voice and Gongs from February 28, 1972 bills Dimitri as producing video images, alongside the collaboration of five dancers. Today, Rhys recalls the concert in a “vague, dreamlike fashion,” and Dimitri identifies the document as typed on his typewriter, but has no memory of the video images or movement. Earlier, in 1971, Rhys had premiered the more familiar Two Gongs—an hourlong exploration conducted with Yoshi Wada of sustained metallic noise, drifting from a hushed simmer to a fiery roar. One is left to imagine how that soundworld manifested into the 1972 bacchanale from the handbill alone.

Less than two weeks later, on March 11, 1972, Rhys and Laurie Spiegel would reunite as musical collaborators to Tony Conrad at the premiere of Ten Years Alive on the Infinite Plain. Conrad had built them both amplified long string drone instruments not dissimilar from Pythagoras’s Monochord. Spiegel played the bass pulse and Rhys held steady in a guitar register. In combination with the just-intoned harmonics of Conrad’s violin, the group drowned out the whirr of four 16mm film projectors, from which frantic loops of strobing black and white vertical lines gradually interlaced to form new image configurations. A surprising detail of The Kitchen premiere is that Steina and Woody were also involved—mixing the live video image for playback on the monitors, deepening the media saturation.

On March 5, 1973, The Kitchen presented Alvin Lucier’s The Queen of the South, a loose gathering of a concert that demonstrates the findings of 19th-century physicist Ernst Chladni: visible particles like salt or sawdust scattered onto a vibrating plate will form intricate floral patterns relative to the harmonic series of each sound, as if blown into place by the wind. Video cameras hung above three 4’ x 4' tables with attached transistors, as subsonic bass tones quietly shook piles of colorful sand into an array of cymatic sculptures. The steady, electrical flow of sound allowed for precise control over the audio spectrum, giving the Chladni figures extraordinary depth. Monitors were spread out in groups of three. One could see what was happening by looking at the monitors or walking over to the tables. Twelve channels of audio surrounded the room with acoustic beats.

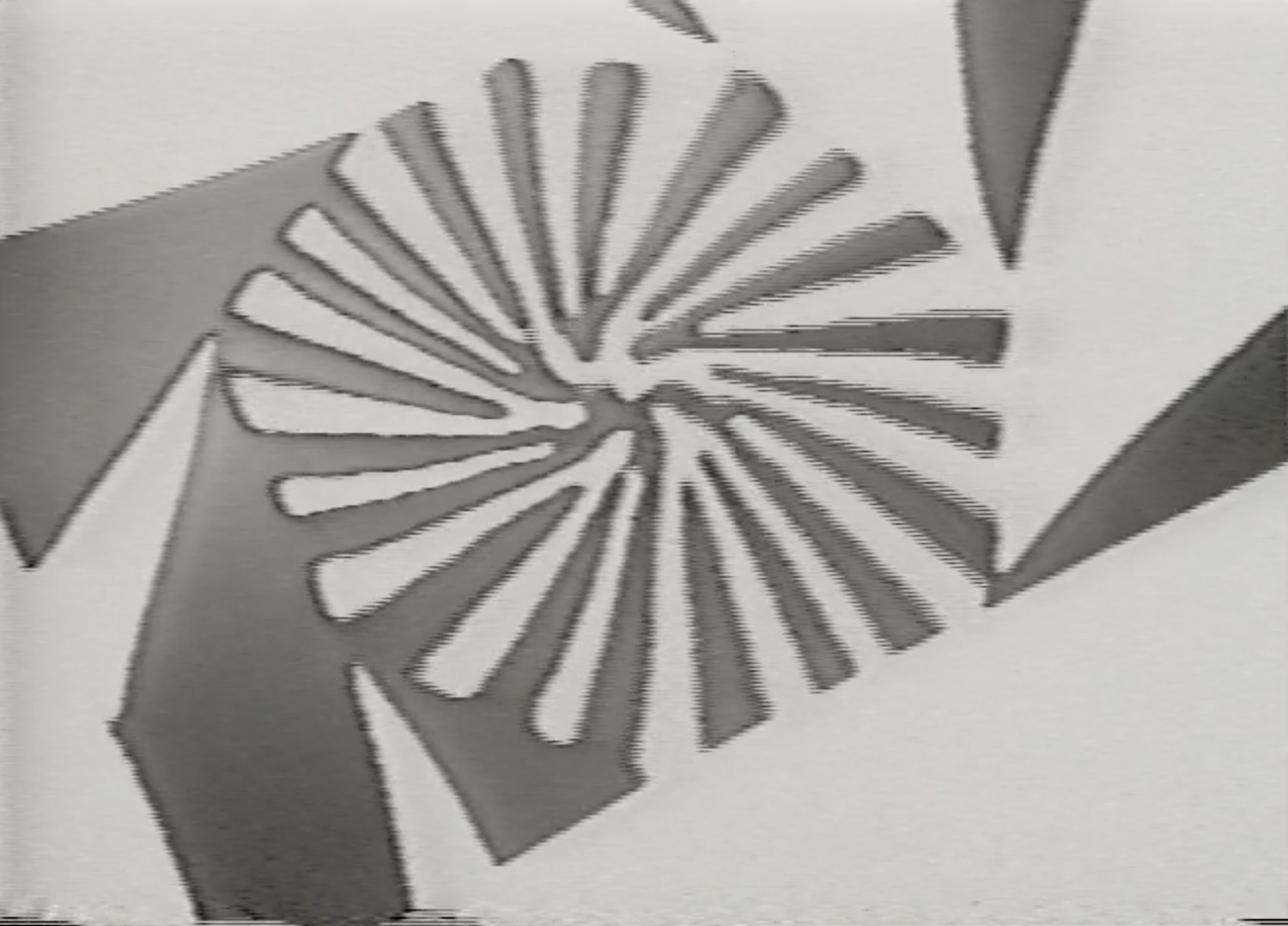

VIDEO SYNTHESIZERS—LIKE THEIR AUDIO COUNTERPARTS—WERE STILL TOO UNWIELDY to live outside of the studio. The Scanimate was one such instrument. It took control of the cathode ray tube’s electron beam with a vector deflection circuit, and could rotate whatever image you wanted in 3D, paving the way for computer graphics. It was quickly put to use spicing up opening-credits sequences and television commercials. Walter Wright worked at Computer Image Corporation as a video animator on New York City’s only available instrument. On Sundays, when the office was closed, Walter would develop his own projects. He put together a piece to Yoko Ono’s “Paper Shoes,” and brought the tape to The Kitchen for a Wednesday night Open Screening. He and his wife Jane were soon welcomed as associates. Bill Etra, who, along with Steven Rutt and Louise Etra (now Louise Ledeen) designed a video synthesizer that expanded upon features of the Paik-Abe, had been immersed in the organization from the get-go. Eric Siegel, another virtuoso video synth inventor, teamed up with the Vasulkas under the title Perception to apply for state funding. Through connections made by Siegel, Electronic Arts Intermix, a then-emerging non-profit started by gallerist Howard Wise, became The Kitchen’s fiscal sponsor, until it gained independence as its own 501(c)(3) in 1973, as the storied Haleakala, Inc. (which remains the organization’s incorporated name today).

Artists championed by EAI—like Steve Beck out of San Francisco, whose Direct Video Synthesizer abandoned the camera altogether by feeding audio signal from the Buchla straight into the TV’s cathode ray tube—found a New York audience for their work at The Kitchen in weekly screenings and annual Video Arts Festivals. Ron Hays, director of the Music-Image Workshop at WGBH sought to notate and “discipline” the analog unpredictability of the Paik-Abe synth with his visualizations of well-known Bartók and Debussy themes—an electronic update of Fischinger’s Hollywood heyday. Hays made the trip from Boston to present his tapes at The Kitchen on May 5, 1973 for a solo concert titled Impressions of Music & Dreams. A popular out-of-town musical guest was the Central Maine Power Music Company, convened by Robert Rutman and Constance Demby, featuring their original sound sculptures—giant sheets of flexible stainless steel attached with metal wires, which could be bowed like cellos or struck like chimes, filling the room with deep groans and piercing rings. Its members appeared as a commune, and encouraged audience interaction. The Kitchen became a space for the group to experiment with visualists and deepen the experience. Pablo’s Lights, an analog light show that also performed a few avenues over at the Fillmore, made an appearance at one engagement. Walter remixed footage of the concert on his Scanimate, which became a tape that played the video festival circuit. CMPMC’s most fruitful collaboration was with Etra, who would essentially become a member of the touring band and participate in a far-out-sounding planetarium event, Astral Projections: A Polyfusion of Media in 1975. (Its poster can be downloaded from the Vasulkas’ bountiful internet archive of event calendars, fundraising documents, concert programs, festival guidebooks, personal correspondences, and press clips related to the history of not just The Kitchen, but video synthesizer culture across New York state and beyond.)

Organic kinds of collaborations among the “cooks” were common. Dimitri brought his tape of a performance by the bansuri player G.S. Sachdev over to Walter, who live-processed the image on the Scanimate, while Dimitri operated the colorizer in real time. The resulting work, which involved no post-production, appears to activate the visual auras of the musicians. On another occasion, Rhys and Shridhar rode the Staten Island Ferry together, taking video of the water as it went by. The footage was keyed like a photo negative. Rhys remembers, “it was very beautiful with this shimmering light, and a drone-like sound that was constantly evolving, made by ring modulators on the Buchla.” Rhys recalls, “I did lots of informal electronic concerts. Sometimes the composer wouldn't show up, and I would just get out a bunch of tape decks, and play loops, and have Dimitri or Shridhar or Woody or Steina put some electronic image on. Lots of informal things like that happened. They would jam.” The loose dynamics of the Mercer Arts Center contributed to the camaraderie. This might mean the constant interruption of an Eliane Radigue concert by drunken glam rock groupies, so much so that Rhys had to lock the door to the venue. Or the many late-night concerts by the groovy Midnight Opera Company that populate the early calendars, where all the cooks mixed their images together at the same time to the cacophony.

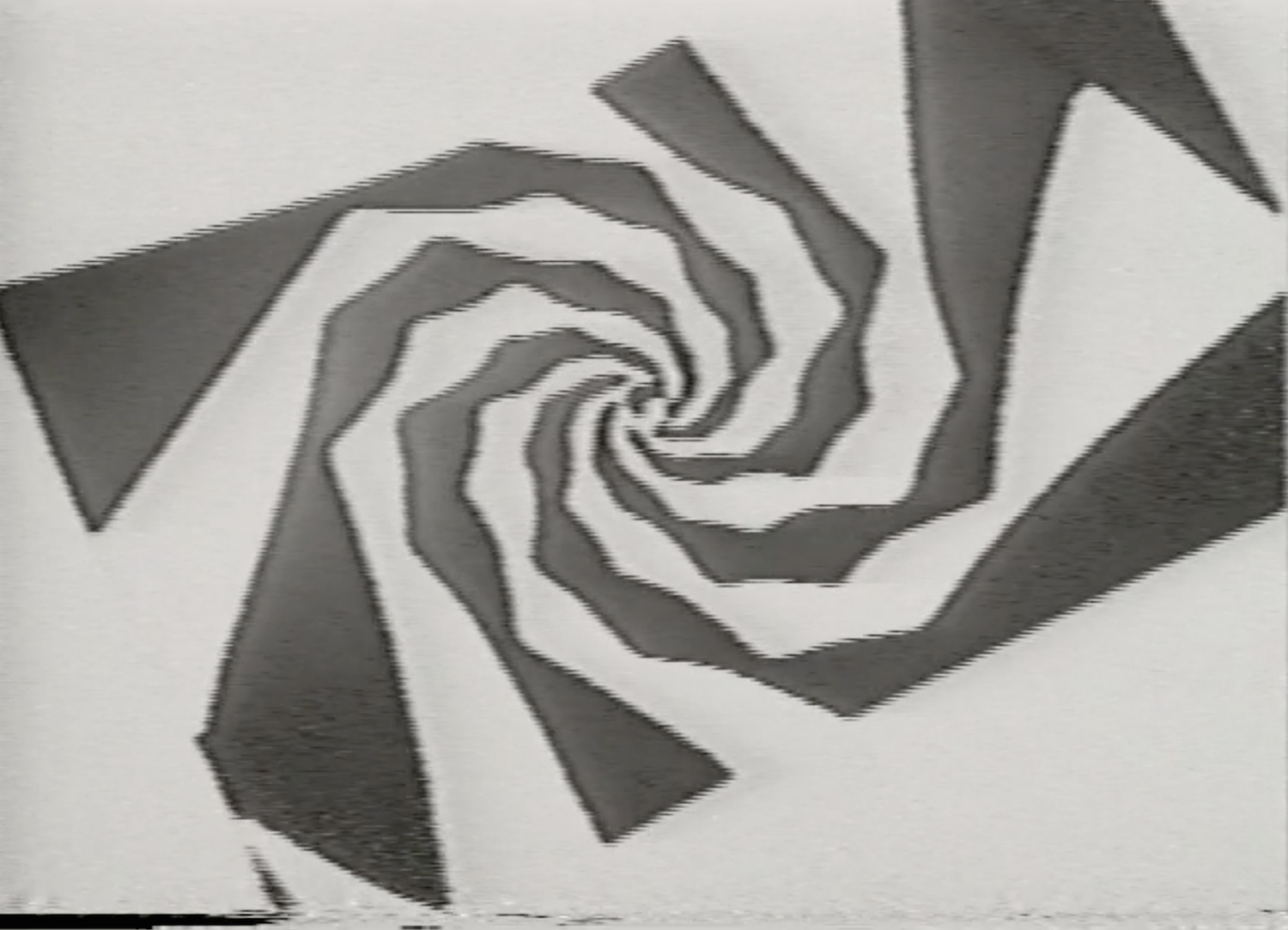

Perhaps no one work exemplifies Visual Music at the Mercer Street Kitchen more than Steina’s Violin Power, which engaged the acoustic instrument as a tool of visual art, getting it to play the television. Steina found success with the Rutt/Etra synth, making the amplified signal of the fiddle modulate the waveform of the video image that depicted her performance, shaking it to the pitch, volume, and rhythm of her expressive and often virtuosic technique. Vibratory consciousness is laid bare here, in a transparent process. The research she conducted in part at The Kitchen would take form as a superlative video in 1978, but this was long after she and Woody had departed Manhattan for faculty positions at the University of Buffalo in 1973, and the various directors would go their own separate ways. (Shridhar, Dimitri and Walter all continued to work with Paik at various points.)

ON AUGUST 3, 1973, THE MERCER ARTS CENTER simply collapsed from neglect. But The Kitchen had slipped away just in time, under the leadership of its first Executive Director, Robert Stearns, to a generously sized loft on Broome Street—in a SoHo surrounded by galleries, not theaters. Video was given a separate viewing room, acknowledging its independence as an art form. The residue of Aquarian spectacular that spilled over from the late 1960s into the first years of the 1970s had given way to the pared-down process ritual that went on to define a generation of New York composers and choreographers. Pictures and cinema took back the Downtown Zeitgeist. Language came into focus. (Rhys returned as Music Director in 1977.)

And yet, inscribed in the origins of The Kitchen is the spirit of Visual Music, where the construction materials of sound and image are one and the same, and things are made to co-exist without hierarchy. Music and art are obviously about much more than just each other, as The Kitchen’s history also generously demonstrates, but the Voltage Control Oscillators of those Buchlas and Rutt/Etras can still be felt fifty years later, vibrating the sights and sounds and bodies that have traveled through its many doors.

BIOS

Nick Hallett is a musician, artist, and curator. In 2005, he organized his first of many programs at The Kitchen, Transparent Processes: Visual Music, Expanded Cinema, and Nouveau Psychedelia. After presenting the Joshua Light Show at The Kitchen in 2007, he became the music director for a decade-long revival. In Spring 2021, he taught a new course on Visual Music at the School of Visual Arts. www.gutcity.com.

In Memoriam: Constance Demby, Jon Gibson, Tony Martin, Robert Rutman, Yoshi Wada, and Woody Vasulka.

Thank you to David Atwood, Alexander Keefe, Andrew Lampert, Mary Lucier, Karl McCool, Laurie Spiegel.

CREDITS & FOOTNOTES

Quotations from Rhys Chatham, Dimitri Devyatkin, and Walter Wright are drawn from interviews conducted by the author in February and March 2021.

Image and composition credits (all other credits included in captions below videos and images):

- Log of Wednesday evening videotape show at The Kitchen, 1971. Detail. To view the full document, click here. 2) Program for Rhys Chatham, Music With Voice and Gongs at The Kitchen, February 28, 1972. To view the full poster, click here. 3) Excerpt from Rhys Chatham, Two Gongs, 1971. Performed by Rhys Chatham and Yoshi Wada. Recorded live by Phill Niblock at Experimental Intermedia Foundation, NYC on December 15, 1989. Courtesy of the artist.

- Poster for Central Maine Power Music Company, Astral Projections: A Polyfusion of Media at the Strasenburgh Planetarium of the Rochester Museum and Science Center, 1975. To view the full poster, click here.