Credits:

J Jan Groeneboer, Alison Burstein, Gilberto Rosa-Duran

June 26, 2024

In January 2024, The Kitchen presented J Jan Groeneboer: Selected Views in its gallery at The Kitchen at Westbeth. The site-specific, multi-channel video installation Selected Views (2024) featured in this presentation is the first iteration of a project Groeneboer has been developing since 2018 through exploratory research, photography, and writing about the singular view from his Brooklyn studio, and, subsequently, through a daily practice of filming the panorama through his window. The views recorded in the video feature disparate elements of the cityscape—including the Brooklyn-Queens Expressway, the Metropolitan Detention Center Brooklyn, a recycling plant, the Gowanus Generating Station, Gowanus Bay, Upper New York Bay, the Port of New York and New Jersey, and the Statue of Liberty—that take on unexpected proximities to one another from the artist’s vantage point. By taking up the project, Groeneboer enacted a durational commitment to witnessing the presence of architectures and systems that are often hidden from everyday life.

In the months following the presentation at The Kitchen, Curator Alison Burstein and Communications Manger Gilberto Rosa-Duran sat down with Groeneboer to reflect on the conception of Selected Views, the experience of realizing the work as a site-specific installation, and how it relates to the artist’s body of work overall.

Alison Burstein: You’ve talked about how you started a regular practice of looking out your window without knowing what it would lead to. After three years of this continuous engagement and accompanying research, there was the moment when you decided that the process would result in a film. Could you talk more about that realization? Was it a decisive moment?

J Jan Groeneboer: Yes, I remember the moment. I was at the window—I don’t remember what I was looking at. I remember how I felt when I realized it was a film.

Prior to that moment, my research process was intuitive. I was looking, photographing, and writing about what I saw out my window. I was reading about the elements of the view. I was enthralled. I didn't consider it research at the time that I was doing it. The view took my attention. That's really what it was. The writing and the photographing were ways to understand that attention.

There are so many factors that went into that moment. One of them being time and that meditative quality of time. Over my years of looking before I began filming, I had a growing understanding of what was happening in the view and the political potential of what I was witnessing. I was looking at the traffic on the BQE and understanding its specificity. One of the first things I noticed was the frequency of Prime, FedEx, and UPS trucks. I never saw USPS trucks on the BQE, and this was during a period where Louis DeJoy was tasked with dismantling the USPS. (1) I understood the direct connection between what I was witnessing with the delivery trucks on the BQE and the increasing privatization of delivery. Then I noticed that the companies that owned the shipping barges coming in and out of the port also owned the shipping containers being pulled by semis on the BQE, and I understood that this connection revealed patterns and movements of global commerce.

I realized the associations I was making through that sustained attention could be best communicated as a film. I suddenly saw an edit of the scenes I had witnessed in my years of looking. I felt elated—all of my cells were singing: I understood the project as a film. And then I began the daily practice of looking with the video camera.

AB: You had been collecting footage for the Selected Views project for years before you and I began talking about presenting the work in its first iteration at The Kitchen. Could you talk about the decisions you made as you began to develop the project for this context—and specifically your choice to present the work in the form of a multi-channel installation? What formal and conceptual considerations followed once you settled on this installation format?

JJG: When I first conceived of this project, I imagined it as a single-channel film. When you and I were having conversations about what it might look like to have this project at The Kitchen at Westbeth, we started to talk about how I could work with this archive of footage spatially. Through these discussions I landed on the idea to make a multi-channel version as the project’s first iteration, knowing that I would return to the single-channel version as a next stage (I am currently working on that version now). Making the multi-channel piece allowed me to sift through the massive archive of footage I amassed from my daily filming practice and pare it down. The process helped me to understand what I had in the archive and to think through duration and differences in attention spans across the three screens. It allowed me to pull a selection from the archive and work within the medium of space, which I am most comfortable in.

There are many aspects of the exhibition space that held exciting parallels for installing this project. I knew immediately that I would leave the windows uncovered—that the view from the Westbeth windows would be an essential part of the installation there.

Then there was the sound of traffic on the West Side Highway filling the space, similar to the traffic on the BQE that is the main soundtrack in the recorded footage in Selected Views. We mixed the sound levels in the installation in balance with the West Side Highway, so it wasn’t always clear if traffic sounds were coming from the soundtrack to the installation or from the highway below. I wanted that kind of seepage in the installation, both sonically and visually.

From the perspective of my studio window, there is a spatial collapse that places the prison, the port, the electrical plant, and the Statue of Liberty in visual proximity. The temporal politics of the view—how the past has shaped its present—are also visible and make clear the daily realities of these infrastructures and their relationship to racial and global capitalism. Christina Sharpe, in her critique of artist Allan Sekula’s work, makes the connection between modern-day shipping barges, the transatlantic slave trade, and colonization. (2) The for-profit system of mass incarceration in the US also shares these same historical roots. When looking at the elements of the view, it’s not just their presence but their interconnected histories that give form and meaning in the present.

Our energy systems which are exploitative and extractive of the landscape are also interwoven with these histories. I also witnessed the billowing pollution from the generating station, the barges, the traffic on the BQE mixing with the already present smog that sometimes shrouds the Statue of Liberty.

And that staute—a gift from one colonizing country to another—is supposed to represent emancipation, democracy, and a country that is welcoming to immigrants. Yet one of the main forces that shaped the landscape visible from my window is the repeated, planned disenfranchisement of Sunset Park, because of its long history as a neighborhood where immigrants live. It was redlined in the 1930s. The construction of the BQE through Sunset Park is only one articulation of the ways the neighborhood has been impacted over time.

The politics of my studio view are revealed through the landscape but also through its contingent history that formed its present. In the installation, I wanted to implicate not only the site of the gallery but also its own views, which include the Hudson River (a waterway that connects to the Upper New York Bay, which my view looks out onto), the West Side Highway, the New Jersey skyline, and also the Statue of Liberty from a different perspective. There are parallels with the site and my view but they are also very different in the ways they’ve been developed.

Gilberto Rosa-Duran: Could you elaborate on why it was essential for your conceptual aims to reveal those parallels for this iteration of the installation Selected Views at The Kitchen?

JJG: In the US, we live in a society with mass incarceration, resource extraction, pollution, and the promise of democracy that has been unfulfilled. We live in dependency on capitalism and the destructive results of that. And we live in relation to all of it. We go about our lives. And so, no matter where we are in New York City, or throughout this country, mass incarceration, capitalism, contested democracy and genocide (both past, ongoing, and current)—they're at the foundation of everything that we're doing all the time.

Part of what really enthralled me about my view is that I couldn't stop thinking about these relationships. I was coming back to my home, to my studio, and thinking: I have to sit with this. This is the reality and this is always the reality. So at Westbeth, having Selected Views play on three screens and then pairing that with the windows looking out at the Hudson River and the New Jersey skyline as the fourth screen—it was important to have those contrasting views happening simultaneously. What is visible from my window in a concentrated area allows those infrastructures to be invisible from other views. That was important to me too—to suggest the presence of mass incarceration, capitalism, and climate crisis and their contingent histories are present in every view, all the time, even if it’s not visible from that vantage point.

GRD: Could you talk about the themes of abstraction and the politics of representation in your art and writing practices?

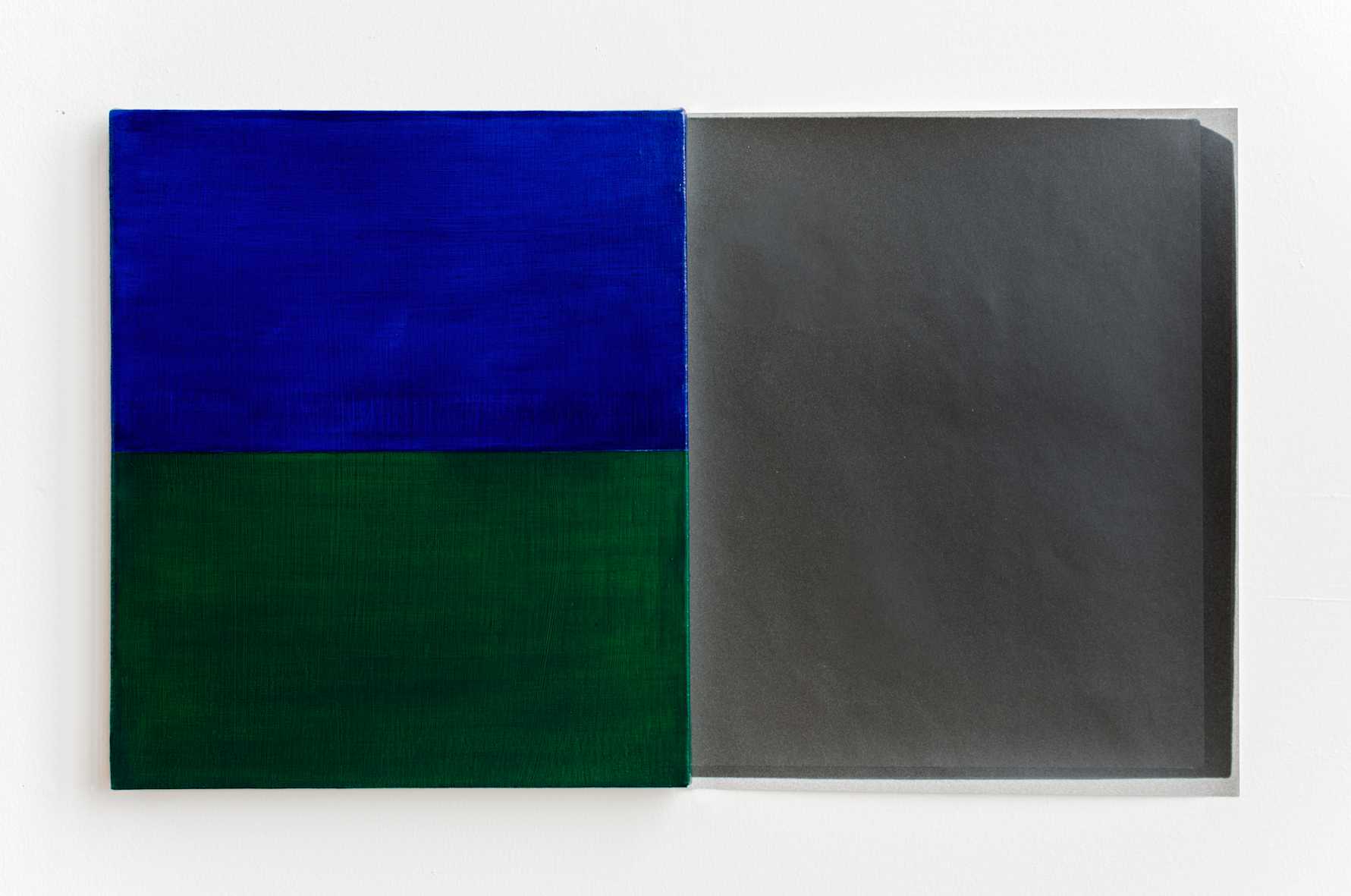

JJG: In my art practice—until Selected Views—I’ve worked in abstraction to address the politics of representation. These modes are intertwined for me. This is particularly true of my human-scale string sculptures where abstraction mediates figuration. These sculptures hang from the ceiling to the floor and appear to stand. They often reference figurative gestures and stances. Blue Shift is a series of diptychs: I pair paintings featuring two colors that become a single tone when viewed under moonlight conditions (when we lose color perception) with photographs of the paintings taken under moonlight. These diptychs are time-based works where over a 24-hour cycle, the painting and its representation (the photograph) move toward and away from each other in perceived likeness.

There is often a durational aspect to my work. For example, the viewer circumvents the human-scale sculptures to see the complexity within their seemingly simple geometry, which is revealed by encountering them from multiple angles. With Blue Shift you have to sit with them over an extended period of time to experience the fullness of the visual possibilities of the diptychs.

In my written work, I have considered representations of trans masculinity in relation to the camera—both still images and the construction of narrative in film. These writings blend personal narrative and criticism: I’m writing about the felt effects of encountering these cinematic and photographic images. In my essay on the film Boys Don’t Cry, I looked at how representation is used as a potential site for erasure—which is a kind of abstraction—of race, gender, and sexuality. (3) My essay “Fragments, Fields, and Bodies: Formations of Selfhood Through Trans Depiction” is a personal account of the ways encountering representations of queer and trans people impacted my understanding of my own gender construction. (4) Abstraction and representation are intertwined with issues of legibility and illegibility: what is seen and unseen.

Shifts in a practice often reveal the aspects that are constant. With the shift from making work that results in visual abstraction to the process of creating representational images for Selected Views, what remained constant was my investment in close durational looking, and a call for sustained attention—what scholar David Getsy has described as the ethics of discernment in my work. (5)

Selected Views is the first artwork I’ve made that is so invested in representational visual images. But they're also images of things that typically remain unseen by design, unless you live or work in the vicinity of these sites or you make a point of visiting them. The architecture of the prison is structured to maximize opacity and limit visibility, both for those on the inside to see out and for those on the outside to see in. The gas released from the power plants is only visible because it obscures and abstracts the landscape behind it. So the piece is an inversion in that these are things that are not supposed to be seen that I spent a long time looking at. These elements are contrasted with the Statue of Liberty, a sculpture whose reproductions and depictions proliferate all over the world. Though what the Statue of Liberty represents versus what we know exists in our reality are very different—and this is a kind of erasure too. This becomes very clear seeing the statue daily in the context of the port, the prison, the generating station, and the BQE.

Sustained attention is a way to see the depth of relationships and politics that are revealed only through unfolding over time.

AB: The sequencing of Selected Views reveals different aspects of the landscape in stages throughout the arc of the video. How did you think about establishing the different elements of what you were looking at and developing the relationships across them throughout the duration of the piece?

JJG: The installation is a loop, so there is an open flow to the edit. It doesn't mean that there isn't a linear edit. But it gets disrupted as viewers come in and out of the installation at different points. That was part of the editing for the installation—thinking in sequences that people might encounter out of order. The linear edit starts by establishing the different elements of the view: the prison, the barges coming in and out of the port, the electrical plant, the BQE, the cranes in the recycling plant, the flocks of birds, the sky, and the statue. I established the elements and infrastructures in the view first, including my window. I wanted the premise of the project to be clear: that the conditions of the piece start with a lived daily practice of witnessing from a single perspective and that all the elements presented are visible from my studio window.

In the multi-channel installation’s edit, the first scene is of the prison. I wanted to start with and return repeatedly to the prison so its architecture would eventually reveal what it is. I knew when I was filming the prison that I wanted to focus on its structure as a building—that what I was seeing is reflective of the overall system of mass incarceration, not an experience of incarceration. I didn’t get too close to the windows. I returned to the lights on top of the prison in both my filming and the edit to focus on the way light is used in this architecture for surveillance and control.

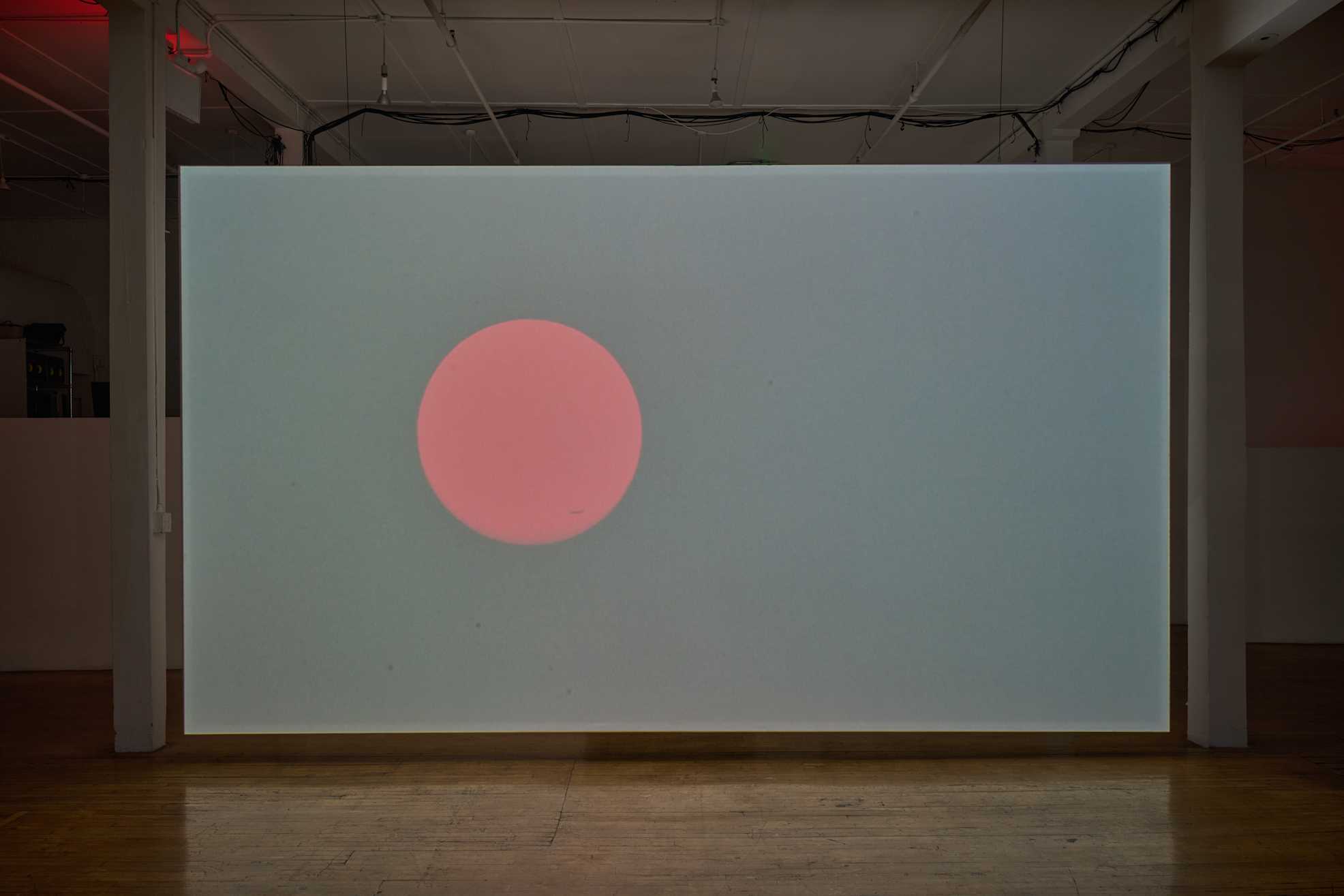

After these establishing sequences, the piece pivots with a scene of forest fire smoke: from that point on I introduce more abstraction in the imagery—first with the red sun visible as a result of the smoke in the air—and I bring in scenes where the amount of gas and exhaust increases in the atmosphere. There is a rain scene that plays on the edge of abstraction and representation that also occurs after the forest fire scene.

There were considerations in the edit in terms of what I wanted to include in the multi-channel installation versus what will be the single-channel film. In an installation, the viewer encounters the piece in spatial relation to their body; this is unlike sitting in a theatre, where you generally give yourself over to the scale of the cinematic world presented. Scale is experienced very differently across these formats. So I thought about these different kinds of viewership in the edit for the installation. There are a few clips in my archive of footage where my silhouette is visible in the reflection of the window. Those clips are important because I want my presence—a single, specific person filming—to be understood as part of the politics of the work. For the multi-channel version, I only included one, because the screens are large and my silhouette in the installation would be at an exaggerated scale. I’m now working on an edit of the single-channel video, and there are more scenes where my silhouette appears in that version.

I also considered how to work with the exaggerated symbolic presence of the Statue of Liberty. I wanted to minimize the focus on it by including only a couple of scenes where it is the main subject. Mostly it appears in the footage in the background of other scenes. There are scenes where the main focus in the foreground is luxury cruise ships, with the statue in the background, for instance.

I think of my practice of filming as witnessing more than surveillance. I’m not the state; I’m not a corporation or a company. I am an individual choosing to do this. And the footage is very subjective. To me the footage that looks the most like surveillance is the footage of the BQE. I think it's because of the proximity to the drivers and passengers. But I really can't see individual people out my window on the BQE. I can see vehicles. I'm seeing the sides of trucks with company names on them. And as a viewer, as a witness, I’m taking note of what's happening. I’m looking back at systems of power. And I think that is a difference between surveillance and witnessing. With these things in mind, I was very careful in my filming and in the edit to make sure that there aren't individual people included.

GRD: You have touched on this already, but in the panel discussion you held in conjunction with Selected Views, featuring Malik Gaines, Zoe Leonard, and Ethan Philbrick on January 13, 2024, you ended with a meditation on beauty and asked the audience to hold both the sublime and the devastating. And in our conversation today you've talked about how the view is so intense and how you were almost horrified by it at first. But I'm interested in the beauty of it as well. For you, when did the view start to become also beautiful?

JJG: Yes, I think it was fast. Part of it was the sky. The view is to the west, slightly angled to the south. I get these incredible sunsets. And there isn’t much blocking the view. I can see very far west unobstructed and there is a great deal of sky visible. That is what drew me to the window at first. Then there is a mesmerizing quality to the traffic. Viewing the traffic is like scrolling or watching a channel of infinite ads. So both of those things probably happened simultaneously, when I would look out and see a kind of traditional sublime. And then I would be enthralled by what I was learning through the traffic because it was really what made me understand the politics of what I was seeing. It was really the traffic for me at first.

A friend said to me that they see my love in the piece more than the devastating. And I think that's what we're talking about when we're talking about the beauty: there's things happening compositionally and with color in the footage, but there's also the reality of how I experienced the view emotionally. That is in the piece. And it's complicated, you know—because love is a part of sustained attention. Even when my attention is trained on all of these violent systems that cause so much harm to people, to animals, to the environment, there is an investment in making them visible to make them addressable as a way to imagine and advocate for other possibilities. It’s devastating to have the conditions for living in this society mean participating in these violent systems. And it's devastating to feel powerless in that, too. Which is also part of why I think witnessing is important as opposed to surveilling. Because the observer who surveils isn't supposed to do anything. The witness can: the witness can act. We can act.

BIO

J Jan Groeneboer is a conceptual multidisciplinary artist, writer, and educator. In his visual practice, he investigates how representation and abstraction connect to different forms of visibility, legibility, and comprehension. Groeneboer often works in abstraction to address the politics of representation. His work has shown at David Zwirner Gallery (2018), Boston University Galleries (2017), MoMA (2016), Art in General (2016), the Queens Museum (2016), CCS Bard Hessel Museum of Art (2016), MoMA PS1 (2015), Contemporary Art Museum Houston (2015), Platform Centre for Photographic and Digital Arts in Winnipeg (2015), Andrew Edlin Gallery (2013), Shoshawna Wayne Gallery (2010), and Exile, Berlin (2010), among others. Essays and reviews have appeared in the New York Times, the New Yorker, Art21.com, Mute Magazine, Artforum.com, Temporary Art Review, and Art Journal, among others. David Getsy’s 2016 essay “Seeing Commitments: Jonah Groeneboer’s Ethics of Discernment” was included in the “Opacities” section of Getsy and Che Gosset’s “A Syllabus on Transgender and Nonbinary Methods for Art and Art History” (Art Journal, Winter 2021). Residencies include Ox-Bow School of Art, the Fire Island Artist Residency, and Recess. He is a grant recipient from Canada Council for the Arts (2018, 2019, 2021, and 2022) and NYSCA (2023), and is a Creative Capital Awardee (2024). As a writer, Groeneboer has participated in numerous panels and symposiums. His essays have been included in publications such as Texte Zur Kunst (2023) and Studies in Gender and Sexuality (2023).

Footnotes

(1) See Alan Rappeport, “Postal Service Pick With Ties to Trump Raises Concerns Ahead of 2020 Election,” The New York Times, March 7, 2020. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/05/07/us/politics/postmaster-general-louis-dejoy.html?searchResultPosition=8; Emily Cochrane, Hailey Fuchs, Kenneth P. Vogel and Jessica Silver-Greenberg, “Decision to Halt Postal Changes Does Little to Quell Election Concerns,” The New York Times, August 19, 2020. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/08/19/business/economy/postal-service-changes-dejoy.html.

(2) Christina Sharpe, In the Wake: On Blackness and Being (Durham: Duke University Press, 2016). http://read.dukeupress.edu/content/in-the-wake.

(3) J Jan Groeneboer, “Erasure through Representation in Boys Don’t Cry,” Studies in Gender and Sexuality, Volume 24, 2023 - Issue 2, 131–134. https://doi.org/10.1080/15240657.2023.2211912.

(4) J Jan Groeneboer, “Fragments, Fields, and Bodies: Formations of Selfhood Through Trans Depiction.” Texte Zer Kunst, May 2023. https://www.textezurkunst.de/de/articles/j-jan-groeneboer-fragments-fields-and-bodies-formations-of-selfhood-through-trans-depiction/.

(5) David J. Getsy, “Seeing Commitments: Jonah Groeneboer’s Ethics of Discernment,” Temporary Art Review, March 8, 2016. https://temporaryartreview.com/seeing-commitments-jonah-groeneboers-ethics-of-discernment/.